Report: Texas Death Penalty System Needs Top-to-Bottom Reform

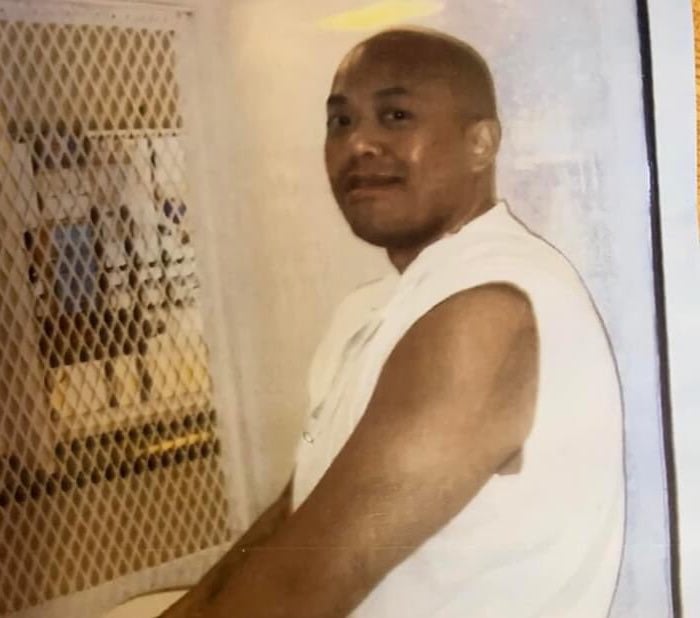

Above: a Texas inmate on Death Row

Today, in the nearly empty Texas capitol, a man who has survived two execution dates held up a 450-page report on the death penalty and shook it.

“I lost 18-and-a-half years,” Anthony Graves said. “Had this study been done 20 years ago, I probably wouldn’t be here today.”

Graves, who spent more than a decade on death row before being exonerated, was the featured speaker at this morning’s panel presenting the findings of the Texas Capital Punishment Assessment Team. The team, organized by the American Bar Association, spent two years analyzing Texas’ death penalty system.

Graves summed up their work. “We have a failed system top to bottom,” he said.

Indeed. The team, made up of lawyers, professors, a judge, a private citizen, and former Texas Gov. Mark White, identified 13 areas in which Texas fell short of best practices—or even, as Paul Coggins put it, short of “adequate practices.”

“If Texas is going to have a death penalty, it has to be the fairest one we can craft,” said Coggins, a former U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Texas. He emphasized that while the ABA had organized the team, its members were all Texans who “looked for Texas solutions to a Texas problem.”

The Texas solution, it turns out, is to do at least some of what other states are doing—banning the execution of people with intellectual disabilities, for example, and using science to evaluate intellectual disability. Or using science at all.

“Texas can’t rely on junk science in capital cases that a judge wouldn’t allow in a slip-and-fall civil case,” Coggins said. And yet it does. For example, in the sentencing phase of capital cases, juries are first asked to decide on a defendant’s “future dangerousness,” which Coggins characterizes as “totally reading tea leaves.” Besides the unscientific nature of predicting future behavior, capital crimes in Texas are always sentenced to either death or life without the possibility of parole, meaning in neither case is a defendant going to be released into society. That makes the question of “future dangerousness” moot, but by posing it before addressing any aggravating or mitigating factors during sentencing, juries are primed to believe that if they think a defendant dangerous, the death penalty is appropriate.

Such is the granularity of the ABA report, which makes recommendations on every stage of the capital punishment system. Law enforcement should use model practices when dealing with eyewitnesses; interrogations should be videotaped; biological evidence should be safely preserved and defendants should be able to have it tested. Crime lab standards should be standardized and test results verified independently and often. Texas should use national standards for arson investigations, give juries better instructions, and provide adequate counsel for defendants in every stage of the process.

Yet even if these and all the other recommendations were all followed, Anthony Graves would not be satisfied.

“For years, we’ve asked the question, ‘Do you believe in the death penalty?’ he said. “I don’t care if you believe in the death penalty. That’s between you and your God. The question is, does the death penalty work?”

Graves held up the massive report again. “This says that the death penalty cannot work. Human error will not allow you to get it right every time. And if you can’t get it right every time, you have no right to be playing with the lives of other people.”