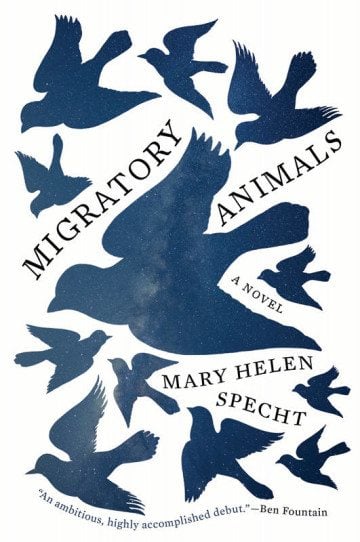

The Observer Review: Migratory Animals, by Mary Helen Specht

Mary Helen Specht reads from Migratory Animals on Saturday, Feb. 7, at 2 p.m., at Books-A-Million in San Antonio; on Tuesday, Feb. 17, at 5:30 p.m., in Jones Auditorium at St. Edward’s University in Austin; and on Thursday, Feb. 19, at 7 p.m., at The Wild Detectives bookstore and bar in Dallas.

Austinite Mary Helen Specht’s debut novel, Migratory Animals, is a tale of flight from and return to the flocks that claim and bind us, the flocks we flee but can’t escape. It opens with protagonist Flannery’s trek to Austin from Nigeria, where she has exhausted the funding for her climate-science research. Back in Texas, she believes, she can gather the necessary equipment to attract a new grant.

Flannery leaves behind in Nigeria Kunle, the man she hopes to marry, as well as the curiosities of life as an expatriate and the comfort of having an ocean between herself and the stateside entanglements she’d rather forget, her mother’s death from Huntington’s Disease and withered relationships of all stripes among them.

By Mary Helen Specht

Harper Perennial

320 pages; $14.99

Flannery’s return to Texas reintroduces her to the familiar, and now struggling, cohort of her college days. This group includes Flannery’s younger sister, Molly, who can no longer ignore that their mother’s battle with Huntington’s Disease is now her own, and Flannery’s best friend, Alyce, who is gripped by depression while trying to raise her sons and maintain a troubled marriage. Three male characters—Santiago, Brandon and Harry, tethered romantically to Flannery, Molly and Alyce, respectively—round out the congregation.

As chapters alternate between these characters’ points of view, Flannery remains at the story’s center, hoping Kunle can secure a visa to the U.S. and unsure she can bear to witness in Molly a repeat of her mother’s decline. All the while, she’s preoccupied with grand visions of a new technology to combat global drought.

At times it can seem that the plot is overloaded with characters and trajectories: two illnesses, an artistic endeavor and a crumbling business, to name only a few. Taken together, the profusion threatens the story’s cohesion. But Specht succeeds in keeping her many threads from unravelling. Her strong, nuanced prose reveals heartfelt insights into her bevy of characters, ensuring a memorable and touching read.

As Specht entwines the fraught glory days of the friends’ college years, family histories, and present-day inner lives, Alyce, a fabric artist, enacts a more literal weaving. She spends her sleepless nights creating an intricate tapestry of the flock in its heyday, hopeful and bonded and expectant. Alyce hopes it will serve as a record for her sons, should life become too overbearing for her to carry on. “She was weaving them a tapestry about her greatest happiness—wouldn’t they eventually wonder why it hadn’t lasted?” The human forms she initially intends to portray finally take form as birds in flight, each representing a different member of the group, participants in a shared migration to parts unknown.

For much of Migratory Animals, these entangled friends behave like the pack of coyotes Alyce observes on her ranch, taking “almost no notice of one another … an apathetic partnership of utility.” But as their wounds pile up, they seek—and find—comfort through reconciliation. As Specht reminds us, though we may migrate to far corners of the earth, we’re never more than a long flight from home.