New Dallas Publisher Aims to Elevate the Status of International Fiction in Translation

Deep Vellum is on a mission to bring international fiction to an American audience.

A version of this story ran in the February 2015 issue.

Above: Will Evans in a Deep Vellum promotional video.

Dallas, you had better get to know Will Evans. That is, if you can catch up with him, and if he’s calm enough to engage in conversation. He doesn’t move or speak at the speed to which you’re accustomed, but if he has his way—and one gets the sense that he usually does—he and his new nonprofit translation press, Deep Vellum, will put you on the literary map.

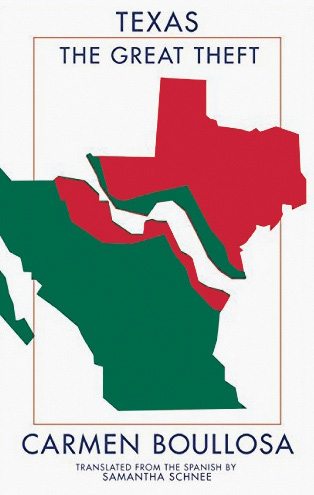

Evans and I met in Manhattan on a bitterly cold November night. He was there for a panel discussion at the Americas Society between Texas literary eminence Rolando Hinojosa-Smith and Mexican writer Carmen Boullosa, whose border novel, Texas: The Great Theft, translated from Spanish by Words Without Borders co-founder Samantha Schnee, is Deep Vellum’s first book. An intense travel schedule—Frankfurt, London, South Korea and points all around the U.S.—coupled with the nasty Yankee wind should have had Evans, 31, worn down. But if he was worn down, I’d hate to see him riled up. At rest, Evans’ chevron mustache is glorious; when he talks, that ’stache becomes a blur.

Chad Post, the notoriously speed-talking host of the international-literature podcast Three Percent, says, “My god, it’s insane; he’s way more hyper than I am. And I used to think I was pretty hyper.” He still is. I try and fail to imagine keeping pace with the two of them in the Rochester, New York, office of Post’s own translation press, Open Letter, where Evans spent the summer of 2012 learning the business as an apprentice. Post makes it sound simple: “We watched a lot of Euro Cup soccer and talked about publishing, and that led to the creation of Deep Vellum.”

Post is one of six Deep Vellum board members, three of whom are located in Dallas, where Evans moved in 2013 after his wife took a job in the city. Once he learned of the pending relocation, his plans to become a book publisher crystallized and he adopted a new mantra: “Going to Dallas, gotta start a press.”

“To only think about Texas from the American perspective is to miss Texas, Texas being such an international state, not just for Mexican culture but for all cultures.”

But translation in the United States is a special thing, if only in that it’s uncommon. Just 1 percent of all books published annually in the U.S. are translated fiction, and only 3 percent are translations of any genre. This so-called 3 percent problem is no nearer to being solved than it was in 2003, when The New York Times ran an article with the headline “America Yawns at Foreign Fiction,” in which Cliff Becker, former director of literature at the National Endowment for the Arts, said, “It is not an exaggeration to refer to this as a national crisis.” It’s “outright dangerous,” Becker continued, for citizens of “the most powerful country the world has known” to be so willfully ignorant of the literature, and by extension the culture, of other nations.

Many, including Evans, lay much of the blame at the feet of the corporate publishing industry, which focuses more on profit than on the promotion of cultural awareness. “This machine … is just churning out garbage,” Evans says. “Ninety-five percent of those books the Big Five publish aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on.”

To Evans, solving that crisis starts at the local level. “Dallas has a robust nonprofit community and arts community, but what it doesn’t have are any literary publishers,” he says. “It has a rich literary history, and it’s just a matter of tapping back into it. I don’t think people care if a book is translated or not. The question isn’t how can you get people reading translations, it’s how can you get people reading good books again?”

That’s a question that Ed Nawotka, a member of Deep Vellum’s board and editor of Publishing Perspectives, a trade publication focused on international literature, struggles with as well. “The American reading public isn’t closed off to translated literature,” he says. “It’s closed off to challenging literature.”

by Carmen Boullosa

Deep Vellum Publishing

$15.95; 304 pages Deep Vellum Publishing

“Challenging” is an accurate way to describe Boullosa’s 15th novel, her fifth to be translated into English. Loosely fictionalizing the 1859-1861 “Cortina Wars” near Brownsville and Matamoros, Texas: The Great Theft bombards the reader with many dozens of characters, most of whom get little more than a passing mention. The voice is a hazy first-person plural, a “we” that includes the reader through a style reminiscent of a screenwriter relating her plotline: “It’s under these circumstances that our story takes place,” for instance. The narration is sometimes omniscient, sometimes not, and choosy about what it divulges. But we usually know where its loyalties lie, which is not often with the Texans, that “handful of palefaces, struggling to cope with a sun that assaulted their senses, [who] acted like they were the center of the world.”

The ensemble cast and smash-cut action make for a whirlwind reading experience. Little wonder that it appealed to someone with so much kinetic energy. “I said that the first book I needed to publish to tell people in Dallas what I’m seriously about would be … a novel about Texas written from the Mexican perspective,” Evans says. “[Texas] is as fair a telling of border history as you’ll be able to get. To only think about Texas from the American perspective is to miss Texas, Texas being such an international state, not just for Mexican culture but for all cultures.”

Though not all cultures think of Texas as being, well, cultured. I asked Post if being headquartered in Texas will be a hindrance for Deep Vellum. “To some degree it is,” he says. “When [Evans] initially said he’s starting a press in Dallas, people were like, ‘What? That doesn’t make any sense, Texas is a crazy place, George W. Bush and cowboys; we can’t take you seriously.’”

But people began to take Evans seriously, Post says, after they saw how quickly he began acquiring the rights to foreign books. Deep Vellum has 10 novels slated for 2015 publication, including The Indian by Icelandic comic, former Reykjavik mayor and soon-to-be Texan Jón Gnarr, and The Art of Flight by Mexico’s revered Sergio Pitol. But will Evans find a readership here for books that don’t have the Texas relevance of Boullosa’s?

“Hopefully I can get more people reading my books in Dallas than would ever read them if I were based in New York,” he says. “I’m creating a new readership.”

At present, you don’t see many Dallasites walking around with translations of Icelandic novels. But Evans knows his market. “If I’ve learned one thing about Texas, it’s that Texans are proud of Texas,” he says. “It’s not just the cowboy chest-thumper mentality; it’s that we like to support things going on within the state. We like to drink Texas wine, drink Texas beer, eat Texas food, go on Texas road trips. There’s no other state that has a culture of literature named after itself like Texana. That’s a special thing.”