Letters from Death Row: The Biology of Trauma

New studies show that trauma biologically alters the brains of young boys in ways that affect their adult behavior.

A version of this story ran in the June 2015 issue.

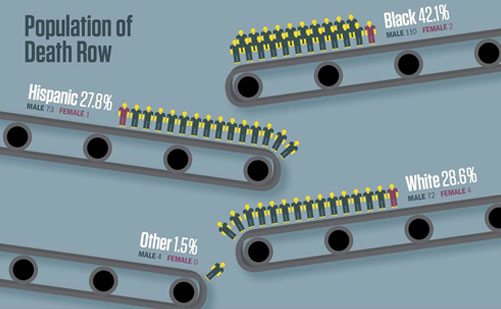

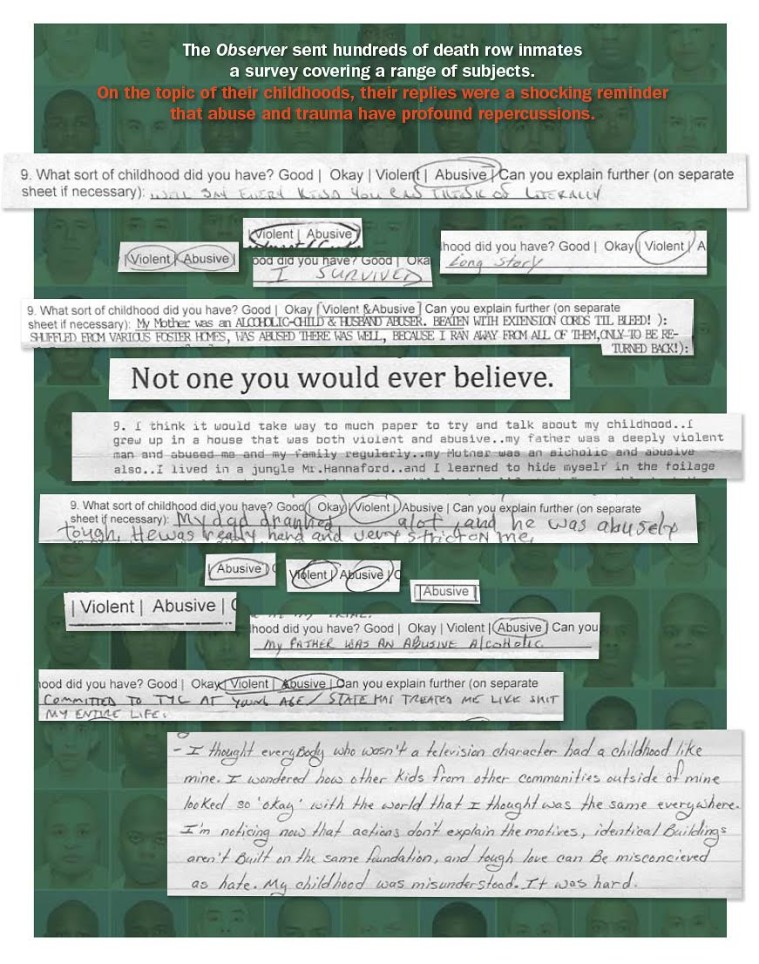

Above: Of the 41 inmates who responded to an informal Observer survey, 22 of them (54 percent) reported have violent or abusive childhoods. An additional nine inmates (22 percent) described their childhoods as “hard,” or said they had some sort of dominant negative issue.

This is the fourth, and final, story in a series.

***

Juan Ramirez grew up in poverty in the Rio Grande Valley, in a neighborhood infested with drug-and gang-related violence. By the age of 10 he’d started smoking marijuana and using inhalants. Within a couple of years he’d moved on to cocaine. By his middle teens he was drinking alcohol and smoking weed daily. A game he and his friends used to play in the Valley, called WAWA, involved spraying paint into a bag, sealing the lip around their mouths, and inhaling the fumes to get high.

Ramirez is the middle of five children and, according to court documents, his mother and father were alcoholics who disciplined their kids by whipping them with belts, clothes hangers, shoes—even tree branches. The severity of those beatings depended on the parents’ moods. Consequently, Ramirez spent most of his time playing outside in the street.

Inevitably, perhaps, he dropped out of school, became a drug addict and spent time in Texas Youth Commission facilities for juvenile offenders. But it was a single incident in 2003 that sealed his fate. One night in early January, 11 masked men burst into a small house in Hidalgo County to steal marijuana. By the time they left, six members of a rival drug gang in the house were dead. Ramirez was just 20 years old and the youngest of those the police said were responsible. Although he wasn’t identified as the gunman, under Texas’ law of parties, prosecutors successfully sought the death penalty.

For the uninitiated, the law of parties holds that if a person “solicits, encourages, directs, aids, or attempts to aid the other person to commit the offense,” then he or she is criminally responsible for the conduct of the other person. Of course the law can be applied inconsistently—and it often is.

This is Ramirez’s 11th year on death row, housed at the notorious Polunsky Unit in the rural East Texas town of Livingston. And his is one of numerous stories of childhood abuse and violence that condemned inmates have told the Observer as part of an informal yet wide-ranging survey of the men waiting for Texas to exercise the most brutal manifestation of its power.

Last year, I sent a questionnaire to each of the 292 inmates on Texas’ death row. It was designed to elicit information often missed in narratives about the death penalty: the effect that solitary confinement has on them; whether they had found religion in prison; and what sort of childhoods they had. I wanted to see if any patterns emerged.

Forty-one inmates responded. Ramirez was among 22 inmates (54 percent) who reported having violent or abusive childhoods. An additional nine inmates (22 percent) described their childhoods as “hard,” or said they had some sort of dominant negative issue—whether it was growing up in poverty and/or in a crime-filled neighborhood or that they endured the potentially debilitating experience of having a parent walk out on them. This is the final story in a series based on information obtained from those responses. Three others, which explore what books the inmates read, the effects of solitary confinement, and how religion factors into their lives, ran previously on the Observer website.

This is not an attempt to retry those cases or to mitigate the harm these men caused. But too often, defense attorneys lack the resources to launch in-depth investigations into the backgrounds of those facing capital convictions. And to quote the Death Penalty Information Center, “Almost all defendants in capital cases cannot afford their own attorneys. In many cases, the appointed attorneys are overworked, underpaid, or lacking the trial experience required for death penalty cases.” The center cites a Dallas Morning News examination of 461 capital cases that found nearly one in four inmates was represented at trial or on appeal by court-appointed attorneys who had been disciplined for professional misconduct. Additionally, an investigation by the Texas Defender Service found death row inmates “faced a one-in-three chance of being executed without having the case properly investigated by a competent attorney.”

It’s also important to acknowledge that the stories of inmates’ childhoods that have emerged from the Observer’s survey are told in the inmates’ own words. When possible, they have been corroborated with court documents or contextualized by news reports.

The responses in our correspondence offer new evidence that supports findings from studies that show a correlation between childhood trauma and the potential for future violent offending. As Texas leads the nation’s death penalty states in executions, the letters also act as important reminders that it’s time we ask what this says about the fractured minds of those we execute and rethink the extent of our moral culpability.

At his trial, prosecutors said Ramirez was a member of a Rio Grande Valley gang known as the Tri-City Bombers. But of the 11 alleged perpetrators of what became known as the Edinburg Massacre, only two received a death sentence. Another, Robert Garza, was executed in 2013 for an unrelated offense. That same year, the alleged ringleader of the gang, Jeffrey Juarez, known as “Dragon,” got 20 years for drug conspiracy and trafficking but escaped prosecution for the killings in Edinburg due to lack of witnesses. Likewise, Reymundo Sauceda, who prosecutors said approved the homicides, had the capital murder indictment against him dismissed. The others in the gang either received prison terms or remain fugitives from the law.

In a letter to the Observer, Ramirez wrote, “I come from the poorest region of the nation, from a poor household. I pretty much had all the strikes against me before I had a choice of my own.”

In their paper “The Cycle of Violence,” published by the American Psychological Association, David Lisak and Sara Beszterczey, researchers at the University of Massachusetts Boston, looked at the life histories of 43 men on death row. They discovered that all of them reported having been neglected as children, that an astonishing 94 percent had been physically abused, 59 percent sexually abused, and 83 percent had witnessed violence in adolescence.

Another study, “Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Criminality,” published in 2013 in The (Kaiser) Permanente Journal, surveyed 151 offenders and compared their answers with a “normative sample” of the population. The researchers found that the offender group reported nearly four times as many adverse events in childhood as the control group.

“The presence of pathological family interactions in the histories of capital murderers is consistent with an extensive body of research demonstrating the role of disrupted attachment and disturbed family relationships in the etiology of violence.”

Many, if not most, condemned men were abandoned by their fathers, lived in foster care, or were abused or neglected, according to Mark Cunningham and Mark Vigen, who 13 years ago conducted a critical review of the literature on death row inmates for the journal Behavioral Sciences & the Law. This observation, they wrote, is supported by the findings of seven of the clinical studies they looked at. “The presence of pathological family interactions in the histories of capital murderers is consistent with an extensive body of research demonstrating the role of disrupted attachment and disturbed family relationships in the etiology of violence,” they wrote. In the United Kingdom (which doesn’t have the death penalty), Gwyneth Boswell, a professor at the University of East Anglia, has spent 22 years conducting research into why young people become violent, and she has identified that trauma experiences in childhood are key features. Two of her studies suggest a high prevalence of abuse and traumatic loss in young offenders’ lives. In one study, Boswell examined the files of 200 young offenders and discovered 72 percent had experienced some kind of abuse—be it emotional, sexual, ritual, or a combination. And 57 percent had experienced the death or loss of contact of a parent. The total number of young offenders who had experienced abuse and/or loss was 91 percent. “Unresolved trauma,” Boswell wrote, “is likely to manifest itself in some way at a later date. Many children become depressed, disturbed, violent or all three, girls tending to internalize and boys to externalize their responses.”

Reading through the stories contained in the questionnaires that the inmates returned, you are confronted with a litany of childhood horror. There’s Eugene Broxton, sent to an orphanage before being cared for by an older sister whose partner then beat him. Broxton was sentenced to death in 1992 after breaking into a hotel room, tying up, robbing and shooting a couple that was staying there. The woman died; her husband survived. In response to Broxton’s defense counsel’s argument in mitigation concerning his home life, the state said, “his sister, his half-sister, his half-brother got the same kind of discipline. And they didn’t turn out to be mass murderers.” Willie Trottie—who was executed in September—wrote that he had an abusive and violent mother who beat him and his siblings with extension cords until they bled. “I was abandoned at a hotel in Houston, placed in foster homes, was beaten there, and I ran away from all of them only to be returned to [the homes] to be abused again,” he wrote. “I was about seven or eight years old.”

Trottie was convicted of the 1993 shooting deaths of his ex-girlfriend, Barbara Canada, and her brother Titus. Prosecutors said he had threatened to kill Barbara if she didn’t come back to him. Trottie admitted shooting the pair but said it was in self-defense after Titus Canada shot him first. (Trottie was arrested after driving himself to the hospital with gunshot wounds.)

In an appeal to the Supreme Court, Trottie’s lawyers argued that attorneys representing him at his original trial failed to produce sufficient testimony about Trottie’s abusive childhood. Maurie Levin, an attorney with vast experience defending capital cases, and who represented Trottie in his litigation concerning the lethal injection protocol, told me that all of her clients survived miserable childhoods rampant with sexual, physical and emotional abuse. “They were impoverished, often entirely outside the social safety net. … How much does it affect later behavior? Every current study says it does—developmentally, neurologically, you name it—and our clients’ stories bear that out.”

Jeff Wood, who was convicted under the law of parties for being an accomplice to the murder of a convenience store clerk in Kerrville in the mid-1990s, wrote that his father used to hit him with a razor strap so badly that Child Protective Services was called. During the punishment phase of his trial, Wood instructed his attorneys not to call any witnesses, and so evidence of his abusive childhood was never presented.

Clinton Young, who faces execution for his part in a double murder in the course of a carjacking, wrote that he grew up with an abusive father and an emotionally abusive stepfather. “My dad beat me with a 2×4 and [kicked me with] steel toe-capped boots. My step dad focused on making sure I feared him and that I knew my real father didn’t care about me—and that I wouldn’t amount to, in his words, ‘a hill of rabbit shit in life.’”

Aníbal Canales strangled his cellmate in 1997 and was sentenced to death three years later. “I think it would take way too much paper to try and talk about my childhood,” he wrote in response to the Observer’s questionnaire. “I grew up in a house that was both violent and abusive. My father was a deeply violent man [who] abused me and my family regularly. My mother was an alcoholic and abusive also. I lived in a jungle, and I learned to hide myself in the foliage that was my life—and hide deep. It wasn’t until late in life that I was able to talk about that part of my life.”

In his findings at Canales’ Fifth Circuit appeal, the judge conceded that “by [his] trial counsel’s own admission [he] did not hire a mitigation specialist, interview family members or others who knew him growing up, or ‘collect any records or any historical data on his life.’” During Canales’ sentencing, the only mitigation presented by his attorney was that he was “a gifted artist” and “a peacemaker in prison.”

The 5th Circuit added that if Canales’ trial attorneys had conducted a mitigation investigation, “they would have discovered an extensive history of physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect. Canales’s mother was an alcoholic who neglected her children, and his father was violent, angry, and irrational. After Canales’s parents separated, his mother married a man who was physically abusive, beating Canales with a belt and fist and forcing him to strip naked prior to these beatings. Canales’s step-father sexually abused his sister, and Canales attempted, in vain, to protect her. The family lived in poor housing, infested with flea[s] and lice and located in ‘gang central.’ Canales’s grandparents were also physically and verbally abusive. Eventually, Canales’s mother left him with his father. The beatings then resumed, and Canales’s father would beat him ‘until his father got tired.’ This led Canales to abuse drugs and alcohol, ‘hook up with the wrong people,’ and begin committing crimes. He lived in half-way houses for part of his teenage years. Canales’s sister stated that the death of Canales’s mother affected Canales severely and that he ‘went off the deep end’ after she passed away.”

Thomas Whitaker wrote that his childhood was emotionally derelict, with no friends or peers and no connection to his family. In December 2003, a couple of weeks before Christmas, Whitaker and his family returned to their Houston home after dinner. Inside the house, a masked gunman shot and killed Whitaker’s brother, Kevin, and his mother, Tricia, before wounding his father, Kent, and Whitaker himself. Although it looked like a robbery, police eventually arrested Whitaker. He later confessed to hiring the gunman to kill his family because of what prosecutors termed an “irrational hate.”

And there’s Jedidiah Murphy, whose parents abandoned him at 5, forcing him to live out his childhood in a series of foster homes. “I could not tell you all of it were you to have all day,” he wrote. “It was violent and it did not help me in life at all. I don’t blame all my life’s ills on my childhood but I never had a shot with the way that I grew up. I learned the wrong way right off the bat, and hell it took forever to see what I was doing was wrong. By that time I was lost to alcoholism like my father and his father and so on.”

As if an abusive childhood weren’t bad enough, Hector Medina, another death row inmate who responded to the questionnaire, spent his in a country torn apart by a bitter civil war.

Medina, who has been on death row for six years, was born in El Salvador in 1979, one of eight children. The family lived in poverty in a house made of sticks held together with mud and plaster, with no electricity. The only source of water was 45 minutes away on foot. The civil war between the militaryled government and a coalition of leftist guerrilla groups began six months after Medina was born and lasted until he was 12.

In an affidavit from Selena Sermeño, a clinical psychologist who looked into Medina’s social history for his appeal hearings, she quotes his brother, Jose Reynaldo, who explained to her what the siblings went through as children: “The Medina children wondered nightly, before falling asleep, if a grenade or bomb would fall on their house, killing them and their parents as they watched the lights of small mortars pass overhead in the darkness.”

According to Medina, when they heard gunfire and grenades they’d hide under the family’s mud stove—the only place in the house he felt safe. When he was 11 he went alone to a nearby river to catch fish and was raped by a member of one of the guerilla armies while another stood watch. Later, Medina was forced to watch his father wrap a neighbor’s dead body in a blanket after he was caught in the crossfire of battle. Inevitably, according to the affidavit, Medina exhibited signs of traumatic stress.

After migrating to the U.S., he found work, eventually naturalized as a citizen, settled down and had two children. But when his girlfriend left him in March 2007, Medina borrowed a friend’s gun and a box of bullets and two days later used the weapon to shoot each of their kids—Javier, 3, and Diana, 8 months—in their necks and heads. He then walked into the front yard and shot himself in the neck, but survived.

Sermeño, who specializes in the impact of political and social violence on moral development, and is an expert in the ramifications of sociopolitical violence on Salvadoran youth particularly, wrote that it was her opinion that violent and traumatic childhood experiences prevented Medina from developing the social and emotional foundations for dealing with life’s most difficult challenges—such as the intense emotional pain that comes from a sense of betrayal, in his case the experience of his girlfriend walking out on him.

A few years ago I conducted some research on the death penalty for the Dart Center, an organization set up to help journalists who cover trauma and violence. Steven Teich, a forensic psychiatrist who has worked in the field for more than 40 years and who has studied death row populations, told me that in his experience, when there has been some kind of violent physical action, it’s highly probable that some kind of serious trauma had occurred in the individual’s childhood, usually before the age of 8. “And this gets translated through non-verbal language in the actions they are charged with,” he said.

Teich told me that if defense attorneys are going to raise issues regarding mental health or the inmate’s state of mind at the time of the murder, it’s important that they look into their history and go right back to that traumatic event. “There are a lot of people who are tried where they do have mental issues, but these are never recognized and not really examined,” he said.

This is my 12th year as a journalist who covers the death penalty, but since my very first visit to the Polunsky Unit back in 2003, it’s been all-too apparent that the people I’ve interviewed share a common story: one of poverty; violent households, violent communities; and lack of opportunities in early life that can help steer us along the right course. For more than a decade I’ve thought about this correlation. So, in sending out that questionnaire, I anticipated some responses alluding to it, but I didn’t expect the volume of physical and emotional abuse relayed in those letters.

Psychiatrist Frank Ochberg, founder and chairman emeritus of the Dart Center and a pioneer in the study of trauma, isn’t surprised. “We knew intuitively that if you treat a child badly there’s a much higher risk for a bad outcome in adulthood,” he told me by phone from his home in Michigan. But it’s only relatively recently that this insight has been studied—and confirmed—by academics.

According to Ochberg, in order to be healthy, rational adults, we require in childhood a reasonable amount of self-esteem and to feel loved, but a great percentage of the human population doesn’t ever get to enjoy that trust, confidence, love or health, and in fact receives exactly the opposite: neglect, abuse and bad examples of how to treat other people. Like any mammal, Ochberg said, we require our biology to respond appropriately to threat—it establishes our essential fight-or-flight mechanism—but we shouldn’t feel threatened all the time. For many death row inmates, though, it’s that system that’s been profoundly damaged.

“These early adverse situations reduce the resilience of human biology and they change us in very fundamental ways. Our brains are altered. And that’s what this research is bearing out.”

Ochberg said it’s not simply learned behavior. “There are a lot of people exposed to a great deal of violence and vengeance every day and they don’t behave in this violent, destructive, criminal way,” he said. “It’s also clear that not all criminality is the product of childhood abuse. But these early adverse situations reduce the resilience of human biology and they change us in very fundamental ways. Our brains are altered. And that’s what this research is bearing out.”

Most stories about the death penalty begin with the moment of violence—that one, often unplanned and unforeseen episode that changed everything.

These stories—in newspapers, magazines and in documentary film—discuss the minutiae of the crime, perhaps relay some element of repentance on behalf of the convicted inmate, and often include interviews with the victim’s family. But what most of these narratives lack is an attempt to establish what went before by taking us back even further into the life of the condemned, before he committed any crime, to that incubation period that molded him—to the trauma. And often that’s the key to unlocking the “why” in these stories.

Just last year, Jeffery Prevost, a 54-year-old auto mechanic, was condemned to die by lethal injection for brutally torturing and killing his former girlfriend and her son after she had broken up with him. Prevost’s defense attorney, Allen Tanner, told the court that his client had had traumatic relationships with women that could be traced back to the time his sister choked to death—an incident that caused his mother to spend the remainder of her life in and out of mental hospitals. What’s more, Tanner said, his client had a daughter who was born with a birth defect and died before the age of 2. But it didn’t sway the jury.

One of the more high-profile cases where childhood trauma has been raised (too late, unfortunately) in mitigating the crime is that of Johnny Frank Garrett, executed in 1992 for the brutal rape and murder of a nun 11 years earlier—a crime he committed when he was 17. As Amnesty International notes, the execution went ahead despite Garrett’s history of childhood abuse and severe mental illness.

According to Amnesty, Garrett was raped by his stepfather, introduced to alcohol and various drugs by family members when he was 10, and forced to perform sexual acts in pornographic films from the age of 14 at the behest of his stepfather, who also hired him out to other men for sex. He was regularly beaten, and once placed on the burner of a stove, resulting in severe scarring, according to Amnesty. The organization says none of this information was made available to the jury at his trial. Though he received a 30-day reprieve from then-Gov. Ann Richards after Pope John Paul II appealed for clemency, Garrett was ultimately executed after Texas’ Board of Pardons and Paroles voted not to commute his sentence.

Clearly not everyone who experiences a violent or abusive childhood goes on to commit heinous crimes. But what is glaringly apparent is that most of those who find themselves in prison for violent crimes have had some kind of trauma in childhood or adolescence.

Clearly not everyone who experiences a violent or abusive childhood goes on to commit heinous crimes. But what is glaringly apparent is that most of those who find themselves in prison for violent crimes have had some kind of trauma in childhood or adolescence. So what should we do with that information?

Ochberg once acted as an expert witness to save the life of a man on trial for multiple murders. “And it turned out he was not only a product of childhood abuse, including sexual abuse, but was a product of abuse in the state hospital to which he was sent as well,” Ochberg told me. “When he was 14 his mother couldn’t take care of him and so she sent him to a state hospital in Indiana, and it was there that one of the employees sexually abused him.”

Ochberg obtained records detailing the abuse, and when he was examined he made the compelling point that, although we try to maintain safety within our institutions, sometimes we fail. “And we can’t then execute the product of our failures when we have a responsibility to care for those people,” Ochberg said. That man was spared the death penalty.

In a way, Ochberg told me, we’re all complicit in having developed these systems that let our own people down. And that’s the bottom line, really. If we fail to catch these men (and women) in a safety net when they’re at their most vulnerable—people such as Juan Ramirez, who endured beating after beating by his mother and father with belts, clothes hangers and shoes—then we shouldn’t be surprised when that violence cycles back around. But we must acknowledge the fact that we have chosen to dispose of these broken souls rather than try to fix them.