Houston’s Absent Son

The Bayou City displays the personal collection of its beloved-in-absentia Mark Rothko.

A version of this story ran in the January 2016 issue.

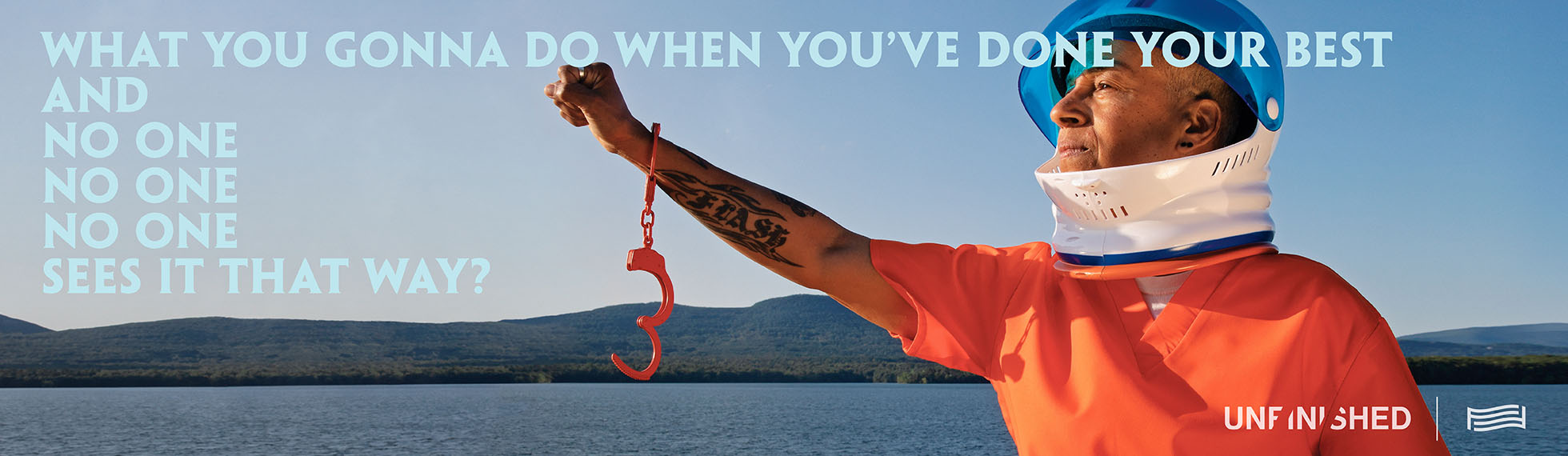

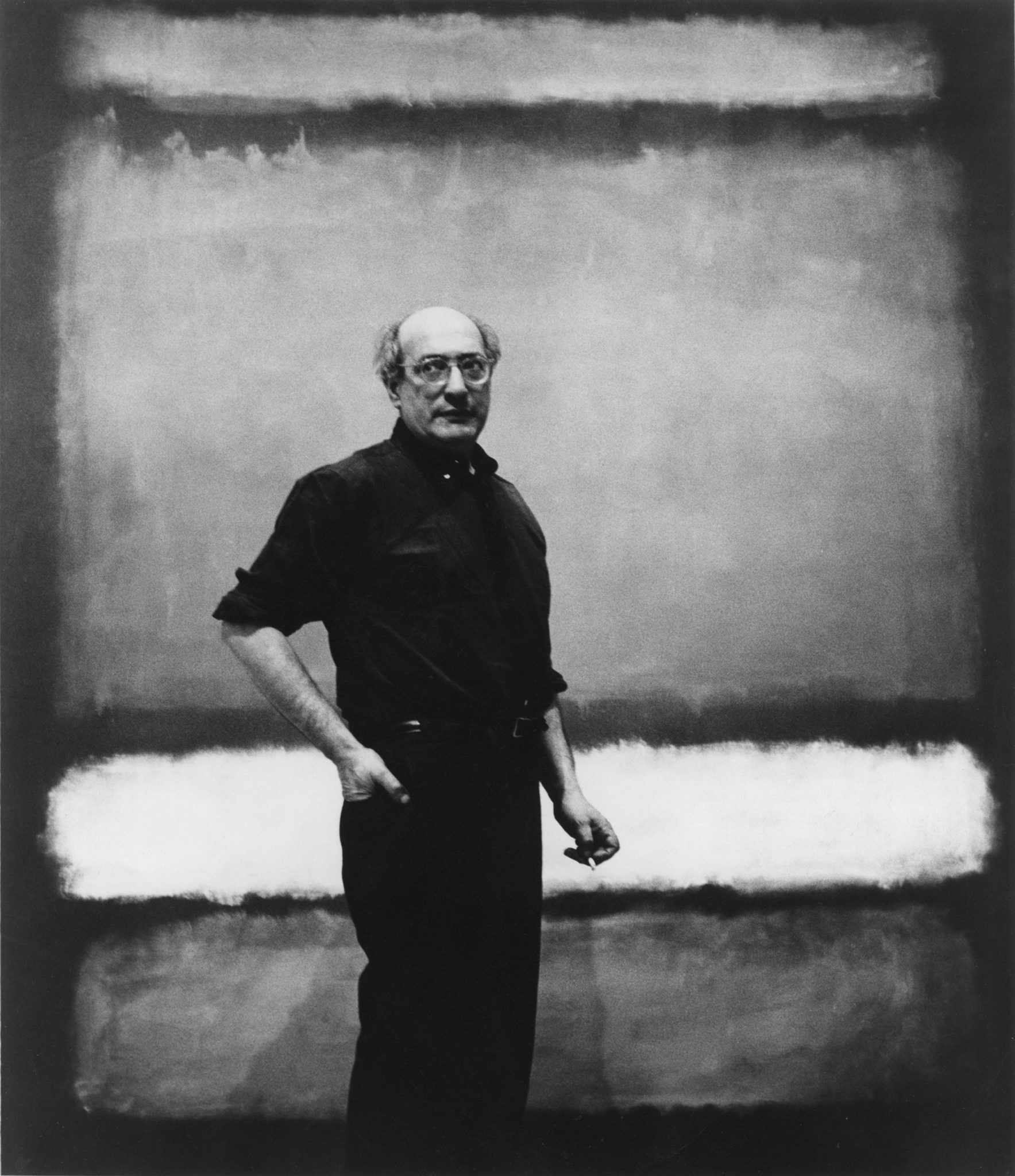

Above: Mark Rothko with “No. 7,” 1960

Mark Rothko never visited Houston in his entire life — not to attend the major museum shows in 1957 and 1967 that helped establish his reputation as an iconic founding father of the then-fledgling Houston art world. Not to visit his patrons John and Dominique de Menil, who chose his canvases as the first contemporary American additions to their fabled collection. Not even to visit the Montrose neighborhood that would become the permanent home of his magnum opus, the Rothko Chapel.

The New York-based Rothko never mentioned Houston in any of his letters or rare public statements before his suicide in 1970, a year before the chapel opened to the public. Though he gave passionate attention to the chapel’s architecture, in particular its roof, Rothko seems to have been more concerned with the aesthetics of the inside ceiling than with any exterior aspect of the building, much less with its setting in Montrose or Houston. It seems entirely possible that Houston as a city — its character, its urban plan, its history, even its future as an international art center — never really crossed Rothko’s mind.

In contrast, Houston has never stopped thinking about Rothko, and the Museum of Fine Arts Houston’s ongoing exhibit is a case in point. “Mark Rothko: A Retrospective,” showing at MFAH through January 24, presents an array of powerful canvases from the artist’s personal collection. The exhibition spans his career, from amateurish figurative and surrealist early works through transitional “multiforms” to the classic color field paintings and the later, darker canvases. The exhibition’s impressive scope serves to underline how much of a footnote Houston was in Rothko’s life, which touched directly on the great events of his era, from the Holocaust to the Cold War. “It’s not to me unusual that a community can develop a fascination with an artist’s work but not have the artist visit; those two things are not incompatible,” says MFAH Director Gary Tinterow. He grew up within biking distance of the Rothko Chapel and remembers excitedly visiting the site while it was under construction, then fancifully planning both a wedding and a funeral there.

Fans of Rothko are well acquainted with the idea that the more of yourself you bring to his work, the more you’ll get out of it. The same has turned out to be true for Houston, which began as an afterthought in the artist’s lifetime and has grown into a key conservator of Rothko’s legacy. “I think of Houston as perhaps the most important city for Rothko,” says Christopher Rothko, the artist’s son and board president of the Rothko Chapel. “Certainly New York City and Houston vie for that honor.”

Where Houston once leaned on Rothko for broader art-world legitimacy, Rothko’s legacy now depends on Houston as a crucial context for interpreting his relevance to 21st century audiences. In a stroke of luck for Rothko, Houston finds itself unusually well equipped for the task — perhaps better equipped than New York City, where the quiet insistence of Rothko’s canvases can feel drowned out by the noise of his biography and artistic milieu, the macho New York School. New York’s Rothko is the painter of bright and decorative canvases sold for enormous sums in his lifetime, the darling of a CIA-financed Cold War cultural campaign, and the celebrity suicide behind a messy estate lawsuit that changed the gallery business forever. Houston’s Rothko, in contrast, is the site-specific artist behind a beloved community space serving ecumenism and social justice; this Rothko, though, is also perhaps a bit of a pious bore, with his big black paintings that don’t do anything. Through the end of January, these two aspects of Mark Rothko can be seen in Houston side by side — one temporarily installed in a museum exhibition, the other permanently soaked into the fabric of a living city. At best, they blend together to give a fuller view of an artist who still deserves our profound attention.

Christopher Rothko, a psychoanalyst-turned-art scholar and author of the recent Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out, has made it his life’s mission to guard against misreadings of his father’s work. In particular, he’s wary of how certain biographical details, including his father’s suicide, might taint viewers’ experiences of the dark, abyss-like canvases in the Rothko Chapel. “Especially with the classic work and the latest and the last works, they are so close to nothing, so close to being a blank slate, they almost invite you to project onto them whatever notions you have of what they might be about based on whatever you might know about the biography,” the younger Rothko warns. “Many people don’t know what to do with them at first. They’re reluctant to have that sort of conversation that’s required to start to get something about them. Putting them in the context of a history or of stories you’ve heard about Rothko makes it easier, but I think it actually defeats the purpose of the work.”

Still, Rothko’s path to Houston is so oblique that biographical background is necessary to address the mystery of his relationship to the city. Rothko was born the son of a Jewish pharmacist in what was then Dvinsk, Russia, where a thriving Jewish com- munity was nearly wiped out by the Holocaust. His family emigrated in 1913, when Mark was 10 years old, settling in Portland, Oregon. Rothko excelled academically and briefly attended Yale University, where he co-founded a progressive satirical maga- zine, the Yale Saturday Evening Pest, to lampoon the school’s racism and elitism. He lost his scholarship, dropped out and moved to New York City, where he found a group of like-minded friends interested in building on the ideas of European Expressionism.

Rothko rarely left New York, preferring to stay in his studio and paint. He was drawn to his native Europe, though, and toured it several times, including an influential 1966 visit to frescoed churches in Italy. He saw himself as working in a grand Western tradition grounded in Christian and Renaissance values and ideas, and, perhaps for that reason, told the critic Dore Ashton that he could never have done the Rothko Chapel as a synagogue. According to Elaine de Kooning, he told an interlocutor who questioned his art’s relationship to Zen Buddhism, “It took five hundred years to produce a Renaissance man: Here I am.”

“The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.”

In contrast to the Socialist Realism favored by Communist state sponsors, Rothko and his peers, including Franz Kline and Jackson Pollock, tended away from figuration or depiction, in search of a sublime or primal viewer response. Some critics called it Abstract Expressionism, others, American Action Painting. Nelson Rockefeller called it “free enterprise painting.” Rothko tried unsuccessfully to avoid such labels.

The Abstract Expressionist heyday brought Rothko increasing fame and fortune, but by the 1960s, he was growing apart from his cohort, eschewing form and color in addition to figuration. By the time of his Rothko Chapel work, completed in 1967, he was, more than painting on his canvases, dyeing them repeatedly with various shades of black. He suffered an aneurysm in 1968 and was forbidden by a doctor from working on large canvases. In 1970, he slit his wrists and died in his studio, where he’d been living for several months estranged from his wife and family.

Especially after his suicide, Rothko was attractive to art critics as a figure of self-obliteration, the alpha and omega of modern abstraction. “Nullifying himself was his discipline of exaltation,” art critic Harold Rosenberg wrote in a New Yorker obituary. “His work denies art, not for the purposes of making more of it, but to be something else,” critic Brian O’Doherty wrote that same year.

As Christopher Rothko suggests, this emphasis on abstraction and self-negation might have led critics to miss an important point. The elder Rothko’s perhaps most-quoted line about his work comes from a 1957 interview with critic Selden Rodman: “I’m not interested in relationships of color or form or anything else. … I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions — tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on. … The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you, as you say, are moved only by their color relationships, then you miss the point!”

Rothko’s relationship with Houston began in 1957, when the curator Jermayne MacAgy organized a solo show for Rothko at the Contemporary Arts Association. The exhibit attracted the attention of John and Dominique de Menil, president and heiress, respectively, of the Schlumberger oil field services company, which is still the second-largest employer in Houston. As Rothko and his Abstract Expressionist peers had unwittingly served patriotic and pro-capitalist CIA aims through the Congress for Cultural Freedom in the 1950s, the chapel that bears his name would become the cornerstone of the Menils’ shared ambition to transform a rough-and-tumble oil patch city into a cultural capital where oil wealth stood for more than crude materialism. Whereas the CIA had supported Rothko for his paintings’ unfettered contrast with Soviet Socialist Realism, the Catholic Menils, both raised in France and involved in left-of-center causes, seem to have been drawn to Rothko’s novel approach to spirituality.

The chapel was originally meant to occupy a central place on the new campus of the University of St. Thomas, which the Menils were underwriting, but Rothko had creative differences with the campus’ star architect, Philip Johnson, who had been an outspoken anti-Semite and supporter of Nazi-style fascism at home and abroad in the 1930s. The chapel eventually found an independent home just off the St. Thomas campus, where it was completed with architects more compliant to Rothko’s vision. At the same time, the Basilian Fathers who ran the University of St. Thomas were uncomfortable with the chapel and its dark, mysterious canvases, so the Menils baptized it an independent 501(c)(3) institution with a secular ecumenical and human rights mission.

The chapel was not well received by critics at its 1971 unveiling, partly because tastes had changed during the chapel’s long gestation period, leaving Rothko ripe for assault by a new generation of art critics. Texan Dave Hickey, who would become well known for his celebrations of postmodern excess in Las Vegas, starred in Charles Dee Mitchell’s humor- ous takedown of Rothko’s transcendent pretensions. Mitchell wrote, “After several minutes, no epiphany is forthcoming. … Hickey leaves a disappointed man.”

Rothko is far from forgotten today; the sale of his 1961 “Orange, Red, Yellow” for $86.9 million in 2012 attests to that. But the art world has inevitably moved on. The geopolitical conflict between Socialist Realism and Abstract Expressionism is ancient history, and without the anti-totalitarian argument for separating art from content, American work from that era can come off as barren, obsessed with decoration and experiments with materials. Certainly, from the late 1960s on, critical and audience tastes have shifted toward art that addresses social, political or environmental themes, engages with popular culture, or moves outside the museum or gallery to make its mark on the world.

Rothko probably saw this change coming. As Greene, the exhibition curator, puts it, by the early 1960s Rothko was “seeing more and more that his painting is being celebrated for being decorative, and of course he wants to be tragic and timeless. So he takes those seductive colors and those hazy atmospherics out of his paintings. At the same time, more and more he’s interested in painting in cycles.” Although he did not move back toward figuration, or comment on the social or political struggles of his times, Rothko seems to have wanted to assert that his paintings were about something — a depth of aesthetic experience, a language of introspection and meditation, a grandeur of theme along the lines of life and death that exceeded anything that could be represented by figure and form. As he said in a 1959 lecture, “My current pictures are involved with the scale of human feelings, the human drama, as much of it as I can express.”

Rothko came to prominence amidst a group of artists, mostly male and often immigrants, who were encouraged to see themselves as demigods.

The Seagram and Harvard mural experiences taught Rothko the difficulty of presenting his work in a context conducive to long-term installation, repeat visits and meditative viewing. In a speculative leap, Greene suggests that for Rothko, Houston was an ideal place to take another shot. “We’re flying to the moon from here in 1966,” she says. “This is Space City. It’s provincial on the one hand, but it is full of ambition. The Beatles come to play here in ’66. And I think the Menils’ ambition is very much a character of the city’s ambition. Make it new, make it great. So you never get, you know, a letter from Rothko saying, ‘Great barbecue! Love the ’ritas!’ But I think, on a deeper intellectual level, the sense of no frontiers that is part of the Houston sensibility created this platform for Rothko.”

Rothko understood that the chapel would be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. On New Year’s Day, 1966, he wrote a brief holiday note to the Menils, which is the closest he ever came to speaking of the relevance of Houston to his life and art. “The magnitude, on every level of experience and meaning, of the task in which you have involved me, exceeds all of my preconceptions,” he wrote. “And it is teaching me to extend myself beyond what I thought was possible for me. For this, I thank you.”

By now, the chapel has survived nearly 45 years of constant operation, hosting all manner of Houston religious services, ceremonies, concerts and social justice gatherings, all with Rothko’s enormous black canvases as a backdrop. Several important Rothkos have hung more or less consistently at MFAH and the Menil Collection, and museum shows have revisited his legacy in 1979 and the 1990s. The chapel has simply stayed put, drawing in generation after generation of art-curious Texans and inspiring the occasional pilgrimage to Houston by Rothko lovers. It also brings in a different kind of international visitor: the recipients of the chapel’s biannual Oscar Romero Award for grassroots work on human rights and social justice. Recent recipients include Nassera Dutour, founder of Collective of the Families of the Disappeared in Algeria, and Dr. Murhabazi Namegabe, who works to rescue and rehabilitate child soldiers in his native Democratic Republic of Congo.

The constant stream of international guests has given chapel observers such as Christopher Rothko a sense of what the place means to audiences from near and far, with and without an education in Western and modern art traditions. “This is truly anecdotal, but my sense is that the Rothko Chapel immediately hits a chord with some people no matter where they’re from, and it remains entirely baffling to many people who may live thousands of miles away, or may live a few blocks away,” he says. “It is what you make of it. A lot of it has to do with how much of yourself you’re willing to give to it, and how much you’re willing to have a foreign experience, to enter into a place that initially feels so other.

“So much of my father’s abstract language was about trying to find a language that wasn’t necessarily going to speak to everybody but was going to break down a lot of borders in terms of who it might potentially speak to,” he adds. “There wasn’t anything particular about this expression that would limit someone from another background, for instance, from engaging with it. I think it has as much to do with your emotional stance as it does with any upbringing or education.”

It’s not just the chapel that provokes this variety of reactions. All of Rothko’s mature works ask viewers to give of themselves — their attention, their benefit of the doubt — before the rewards become evident. Even some who sit for lengthy periods with his canvases come away wondering if the emperor has any clothes. It’s a question Rothko wanted to be asked. As Greene recounts, “He was notorious for inviting people to sit in his studio and look at his paintings with him,” she says. “He’d have a comfy chair or two, and they’d sit for hours, and he would debate endlessly: ‘What do you see? How do you understand the work?’”

These questions can be posed anywhere, but the answers are contextualized in Houston. Here, the Rothko Chapel’s religious architecture and trappings point the viewer toward spirituality and meditation, and the chapel’s social mission offers values more or less congruent with the artist’s. With assurances of ethical and spiritual dimensions, viewers can perhaps feel more confident and cared for while plunging into the abyss of his pure aesthetic language. The Rothko Chapel also provides an opportunity to return, to track a long-term relationship with his paintings — a luxury few artists can claim.

Increasingly, though, others have followed in Rothko’s footsteps, developing permanent installations that more fully shape the viewer experience of their art. Many have found the space and funding to pursue these works in Texas, including Donald Judd in Marfa, James Turrell in Houston and Ellsworth Kelly with his soon-to-open chapel at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin. This new form, halfway between a private museum and a public installation, is rooted in ancient religious architecture, but can be seen, in its contemporary incarnation, as native to Texas. We have developed a national habit of immortalizing artists as they wanted their work to be viewed. Mark Rothko may not have visited in his lifetime, but he was the first such immortal to take up residence here.