Hollywood, Texas

Robert Hinkle’s career started in earnest in the spring of 1955, when the self-described “two-bit” actor from Brownfield, Texas, got a phone call from the Famous Artists Agency asking him to sit down with George Stevens, the director of Shane, A Place in the Sun, and Gunga Din. Up to that point, Hinkle was one of thousands of extras and B-movie stuntmen wandering the back lots of Hollywood looking for jobs on cheaply made Westerns and war pictures. His first break came in 1952 when he doubled for the star of a low-budget rodeo movie called Bronco Buster, a role that gave a kid raised “dang near spitting distance from Lubbock” a taste of life in the movies. With his wife by his side and armed with little more than “guts and BS,” Hinkle headed off to Hollywood and brought some of Texas with him.

The early years were spent as “Cowboy A” or “Cowboy Number 3” on TV shows and in Republic Studio B pictures. Then came the phone call. Stevens was directing an adaptation of Edna Ferber’s cattle-and-oil epic Giant and wanted to see Hinkle. Hinkle was sure Stevens wanted him to star as Jett Rink. He put on his cowboy “uniform” and drove to Warner Brothers.

Hinkle didn’t end up playing Rink. James Dean did. Stevens wasn’t interested in Hinkle’s acting ability at all; he wanted Hinkle’s voice. Aiming to make his film as Texan as he could, the director had decided his star, Rock Hudson, needed to speak with a real Texas accent. The only real Texan anyone could think of was Hinkle.

In his memoir, Call Me Lucky: A Texan in Hollywood, Hinkle brings us back to Hollywood in the 1950s, when a true Texan was apparently an exotic creature. Hinkle was smart enough to harness that exoticism and combine it with his natural-born abilities as a storyteller. He helped sell Hollywood on the idea of the larger-than-life Texan, and convinced the right people that only he could help Hudson, Dean and Elizabeth Taylor find their inner swagger. It’s a gift for self-aggrandizement that hasn’t gone away, as Call Me Lucky is nothing if not a tale of bluster and outsized romanticism. It’s also a tale that will sound familiar to anyone who knows there’s nothing Texans love more than talking about the thousand and one things they assume set Texas apart from the rest of the world.

Nowhere did Hinkle’s skills as an anthropological guide come in more handy than with Dean, a Method actor who wasn’t just interested in dressing or talking like a Texan but wanted to become a Texan 24 hours a day for as long as Giant was shooting (Stanislavsky meets Sam Houston). Hinkle came to see Dean as the Eliza Doolittle to his Henry Higgins, a study in cultural transformation. Hinkle taught the young star how to speak, how to dress, how to hunt rabbit, how to ride a horse, how to mosey, even how to play country songs on the guitar.

Does this “dialect coach” occasionally let his own B.S. get the better of him? Did Hinkle really supply the famous line Jett used on Leslie to drive Bick into a rage (“You always did look pretty. You pretty nigh good enough to eat.”)? Did he suggest the hand gesture Dean would use to refuse Bick’s offer to buy him out in one of the most powerful scenes in the movie? Who can say? But there’s no doubting the impact Hinkle had on Dean and the movie. Giant practically oozes Texas.

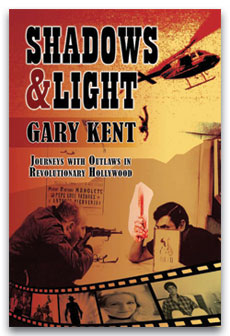

Call Me Lucky lies in sharp contrast to another new book about a man who moved to Hollywood with hopes of cinematic glory, but who ended up a stuntman and a B-movie actor before finding his place in the movie business. Gary Kent’s Shadows and Light, for all its Hinkle-like fascination with oddball characters, movie stars and Hollywood thrills, couldn’t be further in tone from the light-hearted, slap-on-the-back, good-ol’-boy folk-isms of Call Me Lucky.

Shadows and Light. Good and evil. Art and commerce. Life and death. These aren’t opposing terms in Kent’s worldview; they’re the dichotomies born of existence. If Hinkle was a Hollywood child of the 50s, then Kent was his counterpart in the 60s. Just as full of bluster and B.S., Kent was more interested in the political, social, and metaphysical aspects of moviemaking than the man who taught James Dean how to rope a calf. For Kent, the complicated parts are where the meaning is, so he dives into them, passionately and with an attention to detail that would make Henry James dizzy.

Take Kent’s poetic tribute to film crews, which resides somewhere between the lyrics of an Irish drinking song and the Thanksgiving prayer of a modern spiritualist: “The crew, the crew, those hearty sons-a-bitches! … They create shadow and light, call up ghosts, and pierce the veil of eternity. They carry within their trunks … the stuff necessary for the weaving of dreams.” These aren’t the words of a man who stumbled into film for the hell of it. For Kent, movies—especially movies made in the 60s and 70s—were agents of artistic and social change and players in a proper revolution. He, along with buddies and contemporaries Jack Nicholson, Monte Hellman, Warren Oates, Brian De Palma, John Cassavetes, Richard Rush, and others, weren’t just out to make entertainment; they were part of what they considered to be a new wave of “outlaw” American cinema, fiercely independent, light on its feet, and intent on breaking barriers and taboos. Kent had been “weaned on artistic milk and honey from the legitimate theater [in Houston]. I had sashayed in to Hollywood hoping to find work that would challenge old assumptions, scratch some skin, and excite change.” Like so many filmmakers of his time, Kent took a look around Hollywood in the early ’60s, found it embarrassingly out of touch with the spirit of the day, and took it on himself to rattle cages.

That spirit of confrontation and moral daring serves as the backdrop for Kent’s coming-of-age stories as a stuntman and bit player in mid-century Hollywood. He never lets us forget the context in which he and other early independent filmmakers were working: the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, women’s liberation, the summer of love, and the Manson family murders. When Cassavetes got his acting friends together to shoot Shadows, a movie of their own, free from the approbation and control of the industry, they weren’t just breaking down barriers in Hollywood. They were pointing to an entirely different way of living and creating art, where old notions of authority and tradition were vanishing. They were, according to Kent, catching movies up with the times.

Josh Rosenblatt is a freelance arts writer and critic living in Austin.