‘I’ve Been There’

Grady Gaines and Houston’s Rock and Roll Roots

A version of this story ran in the May 2015 issue.

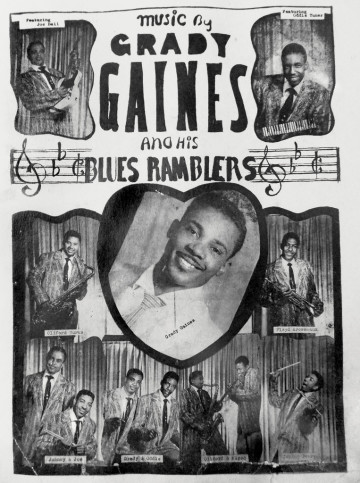

Saxophone legend and bandleader Grady Gaines, born May 1934, in Waskom Texas, became familiar to a generation of Houstonians through a 20-year stint (starting in the mid-1980s) of Sunday night shows at the now-defunct Etta’s Lounge in Houston’s Fifth Ward. A subsequent generation knows Gaines as a mainstay of Houston’s private-party and wedding-band circuit. But Gaines’ career stretches back to the R&B roots of rock and roll, as a session man with Houston music empresario Don Robey’s Peacock Records, bandleader of The Blues Ramblers, and leader of the Upsetters, Little Richard’s, and later Sam Cooke’s, touring band. The following excerpts are taken from chapters 5 and 6 of I’ve Been Out There: On the Road with Legends of Rock ‘n’ Roll by Grady Gaines with Rod Evans. —Brad Tyer

Down At Peacock Studios

It turned out that Don Robey had been hearing a lot about our band playing at Whispering Pines, so he sent his talent scout and arranger, a guy named Joe Scott, to come out to the club to hear us. That’s how we got to be one of the recording studio bands at Peacock. Robey wanted us to play behind artists he was bringing into town to record, like Earl Forest, Big Walter (“the Thunderbird”) Price, Gatemouth Brown—anything he had coming through there that was bluesy and stuff, we could take care of it.

At first, Robey recorded at a studio called ACA Studios before he finished his (own) studio. Sometimes musicians showed up ready to play, but sometimes one of them might be off partying somewhere. Well, Robey would go and find ’im and whoop ’im all the way back to the studio. He felt like he was losing money by them standing him up. I remember this guitar player named Goree Carter, and I had heard that Robey hit him one time. Robey had a record shop and office in the back of the studio, and I heard that he hit Goree so hard that it knocked him through the door of the record shop.

Sometimes people didn’t understand how important it was (to be on time for a recording session), but he let ’em know. Don Robey always treated me wonderful, and I never had no problem with him. I always did what he asked on time. Whatever the case may be, I would be right there. He always treated me fair. That’s all I can say about him. In my opinion, I wish we had a Robey around here now.

Don Robey always treated me wonderful, and I never had no problem with him. I always did what he asked on time.

[Grady’s brother, guitarist] Roy Gaines recalls that Joe Scott, originally from Arkansas, was a talent scout and an in-studio musical arranger for Robey. A sharp dresser, Scott frequented the nightclubs—where Robey rarely ventured—decked out in his signature alligator shoes and dark suits with thin ties, in search of talent to record at Robey’s Peacock Studios.

Born in the Fifth Ward in 1903, Don Deadric Robey founded what would become a legendary establishment known as the Bronze Peacock Dinner Club in 1945 on Erastus Street. Through the 1940s and early ’50s, the Bronze Peacock earned a reputation as one of the finest black owned nightclubs in the country by serving fine food and drink and housing a huge performance stage where top-level performers of the day, including T-Bone Walker, Louis Jordan, and Ruth Brown, delighted the audience, which included some of Houston’s most sophisticated and well-off blacks. Despite its popularity—and possibly because of it—Robey closed the club in 1953. The club became so popular that even some whites began showing up, a development that ran counter to the segregationist mores of the time, and, as a result, started attracting an increasing amount of interest from the Houston Police Department, as did the club’s clandestine, backroom gambling.

After closing the club, Robey, whose mother was white and father was black, turned his attention to recording, booking, and managing some of the talented blues, R&B, and gospel artists in the area at his new Peacock Studios, housed in the same building as the now-departed Bronze Peacock. The first big-time star to record under the Peacock label was Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, and many others would follow, including Earl Forest, Johnny Ace, Big Walter “the Thunderbird” Price, and Bobby “Blue” Bland. To support those artists, he founded the Buffalo Booking Agency and placed it under the astute direction of Evelyn Johnson, who became a critical figure in the development of Houston blues.

Almost from the beginning, Robey was a polarizing figure among musicians, who either sang his praises or damned him for what many believe was Robey’s practice of “cheating” songwriters out of royalty money. Those who knew him say Robey possessed a domineering personality coupled with a quick temper. But it was his dealings with songwriters in particular that caused some to curse him. Although Robey almost certainly took advantage of songwriters who were more interested in scoring some quick cash for a night on the town than they were in securing copyrights for their songs and waiting to see whether they would be recorded and make any money, scarce evidence exists to suggest that Robey engaged in any illegal activity in his dealings with songwriters.

One of these was longtime Texas Upsetter Joe Medwick, who sold many songs, such as “Further on up the Road,” recorded by Bland, to Robey for instant cash. Robey would copyright the songs and assume writer or cowriter credits, usually under his pseudonym of “Deadric Malone,” and later collect the royalties even though it’s highly doubtful that Robey was even a middling songwriter.

Robey’s music holdings would eventually include the Peacock, Duke, Songbird, Back Beat, and Sure-Shot record labels. Upon his retirement in 1973, he sold his holdings outright to ABC/Dunhill for an undisclosed sum. Robey died in 1975 at the age of seventy-one.

The first session I can remember playing on at ACA was behind a white guy. We recorded a 45 with him, but I can’t remember his name. This was around 1953. At that point, we only recorded 45s. We would go in and do a session where you’d cut two 45s. We would have a booth for the horns and drums to keep them from bleeding over, but the whole band would play the whole song at the same time. We didn’t go back and do overdubs much, except for laying the vocals down. If it sounded OK, we’d use that track. If not, you’d go back and try something else.

Some artists would come into the studio after rehearsing and would be ready to lay it down, but some bands would go to the studio and do it on the spot, and that took longer. Don Robey wasn’t involved in the sessions, but he’d be in the control room a lot, listening like a hound dog. The only time he’d come out was if there was something he wanted in a certain spot in a song. Most of the time he would talk to the singer about how he wanted them to express themselves and how he wanted them to say certain words.

Joe Scott would be in there with the musicians, making sure they were playing the right notes and stuff.

Robey had the recording studio and the Buffalo Booking Agency in the same building on Erastus Street, and he could even press the records in the back. I recorded behind so many people that it’s hard to remember them all. We recorded “Whoopin’ and Hollerin’” (Duke, 1953) and “Your Kind of Love” (Duke, 1954) with Earl Forest. We recorded “Dirty Work at the Crossroads” (Peacock, 1952) and “Midnight Hour” (Peacock, 1954) with Gatemouth Brown and “Pack Fair and Square” (Peacock, 1956) and “Shirley Jean” (Peacock, 1955) with Big Walter “the Thunderbird” Price. We also recorded with some of the gospel artists like the Mighty Mighty Clouds of Joy.

By this time, I had switched to playing a Selmer saxophone with a Burt Lawson mouthpiece, and I’ve been buying Selmers ever since. I had just the one sax when I started touring with Little Richard, but later on I got a bunch of ’em. I got five saxes now. I had six, but I gave one of ’em, a King alto, to a little kid that lived next door. I don’t know if he kept playing or not, but I was hoping he would do something with it. I’ve got a Selmer Mark VI now, and I love it. I did most of my recording with that, but on the last album (Jump Start) we did it with a (Selmer) Super 80. I have a black one, a white one, and two gold ones and a soprano, too. The last two saxes I bought were a black Selmer 80 and a white Super 80, and I got those about fifteen years ago, but they’re as good as new. Lester Hill, who played in the Upsetters for a while, fixes my saxes now. He’s over at H&H Music. Back in the ’50s and ’60s, Red Novacs was a salesman at H&H who always looked out for the musicians. I’ve been dealing with H&H for a long time.

Anyway, at this time, you had clubs on just about every corner in Houston, with live music all over the place. The major clubs were the Gypsy Tea Room, the Eldorado Ballroom, Whispering Pines, Club Ebony, Club DeLisa, Club Matinee, and Shady’s Playhouse. You could always find a place to hear some good blues, and they had these jazz jam sessions where there’d be music to cover everybody’s tastes. Most of the crowds was all black, but if we were playing where I knew there would be a white audience, I tried to play some songs that I know the white folks would like. For instance, Gatemouth Brown’s “Okie Dokie Stomp” was a crossover hit. Blacks and whites loved it.

In my opinion, Houston definitely has its own “sound.” I think R&B would stand out here like Chicago blues. On the other hand, people like Lightnin’ Hopkins came from here, and didn’t nobody play no more blues than he did. You got all these guys that migrated to Chicago—Muddy Waters, Jimmy Reed, Little Walter—so I think they accepted that kind of blues in Chicago more than people did here (Houston). I think down here people accepted blues that was more like R&B because we were recording R&B with Don Robey. More R&B was recorded during that time here than in Chicago. In Chicago, they was more dead on Muddy Waters and that kind of blues. We had more horns here—a bunch of horns. That’s what made it R&B when you started adding horns to it.

Like Nothin’ They’d Ever Seen

Joe Bell was a good friend of mine who ran with me for me for me for a while before he decided to buy a guitar and learn how to play it. At that time, T-Bone Walker was like the only guitar player out there, and anybody that picked up a guitar wanted to play like T-Bone. Joe Bell did, too, and he became a big hit around town because he could play just like T-Bone. He wound up playing with my band for a long time, and we became real good friends.

The Blues Ramblers used to play at a lot of car lots on the weekend, where the band would be broadcast over the radio, and people would come out to buy cars while the band would be playing.

The Blues Ramblers used to play at a lot of car lots on the weekend, where the band would be broadcast over the radio, and people would come out to buy cars while the band would be playing. Well, Joe had met this white woman—real nice-looking lady—and he started going around town with her for a few months and brought her to one of the car-lot gigs during the day. We were playing at Whispering Pines that night, and Joe’s girlfriend said she had a pretty white girl for me to meet later, but I had something else to do, and I couldn’t be with that girl that night.

Joe’s girl showed up at Whispering Pines for our show, and while we were playing, the police came into the club. They took Joe off the stage and beat him up terrible. I was lucky because I would have been right there with him if that white girl had been there for me. Joe stayed in jail for a couple of nights, and his girlfriend went down and bailed him out. Right after he got out of jail, we had another gig to play, but I had to turn his guitar up and down for him because he couldn’t hear because they had beat him up so bad. He’s lucky they didn’t kill him.

Houston could be pretty rough back then, but you wouldn’t have no problems (with white people) if you knew where you were at and acted accordingly, and that’s what I did. I mean, if you know fire’s gonna burn you, you ain’t gonna stick your hand in it. I tried to live my whole life like that, and that’s why I’ve lasted as long as I have. I had a lot of close calls, but me handling myself the way I did helped to prolong my life. Joe messin’ with that white woman in public just brought too much attention to himself.

About this same time (1953), Little Richard was playing a lot around town with this band called Raymond Taylor and the Tempo Toppers. He did that for a few years. The group was Taylor playing trombone and keyboards and his wife, Mildred, playing drums. Richard was one of the singers, along with Gil Moore, the bass singer, and Jimmy Swann and Billy Brooks. They played a lot at the Club Matinee and all over the South—Oklahoma, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia—but Houston was their base because they was being booked by the Buffalo Booking Agency.

The Tempo Toppers were real popular in Houston because Richard was like nothin’ people had ever seen. They played a lot of places, like the Whispering Pines and the Anchor Room, and they played a lot of the after-hours shows, too. After the big-name acts would play their shows, they would go back to the hotel and party and jam, so everybody would flop there. That’s where I first met Richard, but he had heard me at Peacock Studios. I sat in with the Tempo Toppers one night at the Anchor Room, and shortly after that, Richard had decided to leave the Tempo Toppers and go out on his own. Robey had already started recording him and Gil Moore and Billy Brooks, but Richard was already becoming a hit because he was out front of the Tempo Toppers. We recorded a couple of songs with the Tempo Toppers back then, one called “Fool at the Wheel” and a tune called “Rice, Red Beans, and Collard Greens,” but they wasn’t hits or anything. But when we played a town, and if they hadn’t already heard it, after they heard us play it, it sold like like crazy and became the number-one hit in that town.

Richard asked me to play some dates with him in Oklahoma, Georgia, Dallas, and different places, but this was before he had made any recordings that were hits, although he had recorded some mediocre things at Peacock. My first impression of Richard was that he was something really different, and the people just loved him. I thought the world of him and thought he was a star that was going to be an even bigger star.

The Blues Ramblers was still real popular all over town, and we had all sorts of women following us wherever we played, and they would be so sweet and fine that you just couldn’t hardly resist. I remember one time we was playing at the Eldorado Ballroom, and this man wanted to kill me over his girlfriend. I had taken his girl, and we had sex in the car, and he saw us coming back into the club. The band was still playing, but it was near the end of the gig, so I left the stage and had to back up all the way out the door from the bar at the front, through all the people and out the door. I kept my eyes on him the whole time. I think he had a gun, but I wasn’t sure. I kept looking at him, and he kept looking at me as I backed down the steps and jumped into my car. Somebody else was driving, and we got the hell out of there. That was a real close call that was right before “Tutti Frutti” hit, and I went on the road with Richard.

But before “Tutti Frutti” became a hit, Richard did a lot of recording at Peacock Studios for Don Robey, but I know Richard and Robey had some problems.

In The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Authorised Biography by Charles White (London: Omnibus Press, 1984, 37), Richard said his constant challenging of Robey’s authority resulted in several clashes. He recalled a specific confrontation with the no-nonsense studio boss:

LITTLE RICHARD:

He jumped on me, knocked me down and kicked me in the stomach. It gave me a hernia that was painful for years. I had to have an operation. Right there in the office he beat me up. Knocked me out in the first round. Wasn’t no second or third round; he just come around that desk and I was down! He was known for beating people up, though. He would beat up everybody except Big Mama Thornton. He was scared of her. She was built like a big bull.

Richard liked the way [upsetter saxophonist] Clifford [Burks] and I played because we played so good together. Clifford and I had a sound that no other two tenor players in that time had. It wasn’t often in rhythm and blues and rock ’n’ roll that there was two tenor players (in a band). Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt, they had their sound, but they were playing jazz. But now Clifford and I had a sound that everybody was talking about. I mean all the musicians was talking about it. We had a hell of a sound together, but we did a lot of practicing together. We’d practice all day and cook up red beans and rice and stuff and keep right on practicing. That was before we went to meet Richard. Then after we joined him, we just kept on practicing, but we really put that sound together before we went out there on the road. So when Richard sent for us to join his band, it wasn’t no sweat for us to learn his songs because we’d been playing ’em for so long.

Gaines and Burks would continue their musical collaboration for nearly three decades until the 1970s, when both men left the road behind. Burks eventually settled in New York, where he continued to play locally throughout the 1990s. Now retired and not in the best of health, Burks and Gaines remained good friends and talked frequently to reminisce about the old days and the many stages and experiences they shared as members of the Upsetters. Burks passed away in

October 2014 at age 84.

If you know fire’s gonna burn you, you ain’t gonna stick your hand in it. I tried to live my whole life like that, and that’s why I’ve lasted as long as I have.

Clifford played a little different than I did. He played a little bit more jazzier and a little bit smoother. I always wanted my own sound, so my sound was like between Illinois Jacquet and Arnett Cobb, and Clifford, he had a big tone—course we both had big tones—but his was smoother than what I played. So we took those two sounds and put them together, and that’s what made it so good.

Plus practicing together all the time, when we’d make a run, if I get that first note, whatever note I have, whatever note he get, we just automatically go on into it—into whatever we’d be playing. See, when you practice together a lot like that, you know what each other’s doing, and wherever one go, the other one knows where to go to match it. It seemed like we were born to make music together.

Excerpted from I’ve Been Out There: On the Road with Legends of Rock ‘n’ Roll by Grady Gaines with Rod Evans, published by Texas A&M University Press, 2015, 192 pages, $23. Info at txlo.com/gaines.