Exxon’s Utopian Vision For North Houston Is Eerily Familiar

A version of this story ran in the February 2013 issue.

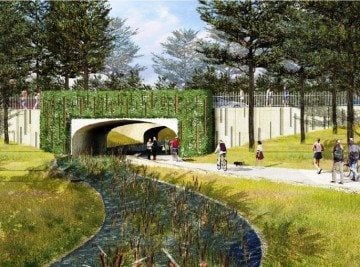

Above: Artist’s rendition of the new Exxon Mobil corporate campus under development in North Houston, near the junction of Interstate 45 and Hardy Toll Road.

Along Interstate 45, about 30 miles north of downtown Houston, an unmarked driveway veers off the access road into a pine forest, past overgrown manmade ponds and an abandoned guard shack, dead-ending at the half-burned shell of D.B. Cooper’s Mansion, a short-lived strip club.

Before it was shut down in 2009 for failing to obtain a sexually oriented business license, D.B. Cooper’s hosted an Oil and Gas Industry Night every Monday. The date of the club’s closure was inopportune. Just two years later the site was revealed to be prime real estate, accessed by what will soon be known as Energy Drive, not a quarter-mile from ExxonMobil’s new 385-acre corporate campus.

The 1,800 acres of forest surrounding the charred strip club is currently being thinned to make way for Springwoods Village, an eco-themed master-planned community boasting Exxon as its anchor. Though the company’s Irving headquarters will remain, by 2015 Exxon plans to have consolidated about 10,000 workers from offices in Virginia, Ohio and Houston into this new corporate sanctuary. Along with New York City-based Coventry Development Corporation, Exxon is creating a company town from scratch.

A dozen cranes tower over the pines, and freeway signs direct construction trucks toward the site, code-named Project Delta. When it’s complete, the campus will boast a design intended to reflect the company’s “value set and culture,” according to a company video presenting a digital model of the development. A cluster of low-rise buildings surrounded by treetops will form an “urban vibe” core. The campus’ main building—its gateway structure—will be composed of what look like large glass blocks, one of which will extend, almost hovering, over a placid lake. Employees will walk leafy promenades beneath transparent awnings, not a car in sight.

Exxon calls Project Delta a “campus for the future,” and it’s a far cry from the urban ideals once promoted by oil companies. In 1937, Shell’s “City of Tomorrow” advertising campaign situated America’s corporate future in downtown utopias crisscrossed by wide freeways, devoid of trees and sidewalks. Exxon’s own 45-floor tower in downtown Houston, built in 1963 and recently sold to a San Francisco-based real estate company, is emblematic of that vision. Yet many oil companies long ago traded their urban high-rises for, or supplemented them with, pastoral suburbs. Several, including Chevron Phillips and Baker Hughes, have already opened headquarters or branches in north Houston.

Unlike its corporate forebears, Exxon’s vision for north Houston is not limited to office space. The company will make an even larger imprint on the area through Springwoods Village, which is being planned by private developer Coventry in close coordination with the oil company.

Springwoods’ neighborhoods will be set amid roadways lined with wide sidewalks, nature trails and upscale shopping centers—a footprint that will “balance nature, urbanism and diversity,” according to the Springwoods Village website.

“We’re trying to reduce the energy consumption within the community and enhance the quality of the environmental aspects as well,” said Keith Simon, executive vice president of CDC Houston, a local subsidiary of Coventry. Such a vision is particularly appealing to corporations eager “to recruit and train the next generation of employees who don’t want to be as dependent on their cars.”

Over the next two decades, Coventry will build 5,000 residential units designed to house between 12,000 and 15,000 people. One of the first Springwoods neighborhood plans to be made public is Harper Woods, 16 acres of quaint houses and townhomes modeled from a mishmash of historical Southern styles. Starting at $339,000, these will be some of Springwoods’ cheaper options; more exclusive nooks, built by Arizona-based homebuilder Taylor Morrison, could top $1 million.

Coventry has owned its north Houston properties since 1961, when the company was known as Chrymirene. The land sat undeveloped for decades, until Coventry sold Exxon the 385 acres for its campus. Shortly after, Coventry announced it would build the $10 billion Springwoods development.

In November 2012, Simon told local media, “We talked with [Exxon] about where they wanted to be located on our land and then created our mixed-used development around it.” After Exxon purchased the property in December 2008, Simon was quick to confirm that Exxon is “a part of the Springwoods Village planned community.”

Two decades ago, Exxon wouldn’t have had to outsource its master-planned neighborhood to a private developer; the job could’ve been performed by its in-house subsidiary, Friendswood Development Corporation, which planned and built well-known communities like Clear Lake City near NASA and Kingwood northeast of Houston, both now annexed by the city. In 1995, Exxon sold Friendswood.

With Springwoods, Exxon is showing that even if it’s out of the residential real estate business, it still has the power to shape a city.

But not without an assist from local authorities. In August 2012, Harris County Precinct 4 Commissioner Jack Cagle spoke enthusiastically about the development in a promotional video released by Coventry. Two months after the video’s release, Harris County Commissioners Court approved a deal to reimburse Coventry up to $82 million for building out Springwoods’ infrastructure, including roads and parks. This is the first such deal—called a 381 agreement—in Harris County, and Cagle said the deal contributes to the cost of infrastructure that the county would ultimately have had to build itself. More than $35 million worth of infrastructure has already been erected in Springwoods, some of which—street signs and stoplights—can be seen beyond the manned security checkpoint at the site’s entrance.

One reason Cagle is so passionate about Springwoods is his belief that the community will “integrate man with nature.” It’s a claim parroted by Springwoods and its master-planned neighbor, The Woodlands, but it’s a convenient fiction. The area’s actual history, and future, are more complex.

The area was once dotted with sawmill towns like Tamina, with vast tracts of land owned and exploited by timber companies. In 1964, Texas oilman George Mitchell bought 50,000 acres from the Grogan-Cochran Lumber Company, parts of which would be developed a decade later into the area’s first master-planned community, The Woodlands. Now, the area’s former big-name forest barons are enshrined in the communities that supplanted the woods; Grogan’s Mill was the first neighborhood built in The Woodlands.

It wasn’t long before north Houston became an established suburban enclave, with developments like Springwoods looking to the remaining forest as a boon for marketing their communities as “sustainable,” even as they increase the area’s population density and chip away at its woodlands.

Just like The Woodlands, Springwoods is more a tribute to the idea of nature than actual preservation; nature is valued in as much as it gives prestige and seclusion to homeowners or forms a “tree buffer” to block unsightly strip malls. The Woodlands, in fact, is in the midst of a water crisis, with local officials estimating that millions, possibly billions, of gallons are wasted each year.

Springwoods’ sustainability credentials—though somewhat more thought-out than those of The Woodlands—also rely on dubious visual cues. Its sole nature preserve is 150 acres, the same amount of land that Coventry sold to the Texas Department of Transportation for construction of a 12-mile connecting segment of the Grand Parkway, Texas’ largest ring road at 180 miles. Shortly after Coventry purchased its north Houston properties in 1961, the company began pushing for the parkway, which, when completed, will situate Springwoods at a major new Houston crossroads.

And as much as Simon hopes that Springwoods will “show people a different way to live,” with its “vibrant, urban mixed-use center,” the development is in fact a repackaging of practically the only way Houstonians have ever known how to live: in a neighborhood located off a freeway platted by an oil company and a corporate developer.

Houston is full of “cities of the future” like Springwoods, developments once trumpeted as the new way to live and work, only to be replaced a few years down the road by the next best thing. Just look to Greenspoint—12 miles south of Springwoods—built and conceived decades earlier by Exxon’s Friendswood Development Company.

Today, the first thing that strikes one about the Greenspoint area is the almost desolate mall and its oceanic parking lot. It was here that, in 1991, an off-duty deputy sheriff was abducted and murdered, and her Ford Aerostar burned. The notorious crime helped solidify the area’s unfortunate modern moniker, “Gunspoint.”

Just years earlier, Greenspoint area ads had boasted, “We’re right in the middle of Houston’s future. Come look us over!” The development, then on the edge of Houston’s bulging northern perimeter seven miles from George Bush Intercontinental Airport, was closer in vision to Shell’s “City of Tomorrow” than to Exxon’s future campus: freeways, curtain-walled towers, and the eponymous mall.

Now that Exxon is planning to relocate the majority of its 5,000 Greenspoint employees to the new campus, the towers that once appeared so fashionable look like relics of a bygone era. Nature preserves, not malls, are the newly coveted neighbors of business parks. Tom Wussow, former vice president of Friendswood Development in the early 1990s, makes the point in an interview with the Observer: “The whole mall concept has run its course to some degree.”

But in 1976, when the Greenspoint Mall was built, it was the amenity that got people “excited” to develop this tract of north Houston, according to Wussow. Friendswood bought hundreds of acres in 1978 surrounding the mall and began to build what it envisioned as a world-class suburban business district, a hub for the corporate jet set, 5,000 apartment units and a series of reflective office towers named 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. It seemed to be a perfect embodiment of Commissioner Cagle’s vision of north Houston as a business-friendly place where “you get off the plane at the airport, put on some Justin boots and ride through our trail system.” Soon, Anadarko—now in The Woodlands—and other energy companies flocked to Greenspoint.

An area once dense with trees, interrupted only by a winding bayou and a railroad, was completely transformed. Now, from the tops of Greenspoint’s towers you can look down at a convergence of 20 lanes of traffic. On a clear day, you can see Exxon’s refineries on the coast, some 30 miles away.

In the 1980s and ’90s, Friendswood Development exercised enormous influence on the shape of Houston as Harris County’s largest landowner and Texas’ largest developer. FDC was even asked by the city of Houston, according to Wussow, to weigh in on the city’s development code in the 1970s, and again in the 1990s.

With Greenspoint, Wussow said, Friendswood “pulled out all the stops in the development planning.” Through a precise commercial code, Friendswood dictated everything from the species of trees to be planted to the surface texture of buildings. Great effort was expended to make sure Greenspoint conformed to a specific image, one that would preserve its desirability as office space.

Greenspoint was also cheap. In the ’90s, Exxon claimed tax exemptions on 250 acres of undeveloped Greenspoint-area land then appraised at $4 million. Land that should have netted more than $20,000 in taxes for the nearby school district generated just $222.38 due to its classification as agricultural land, a tax loophole revealed by a 1993 Houston Chronicle investigation.

Then, as the early Greenspoint towers opened for business, the neighborhood seemed to slip out of Exxon’s control. In the mid-1980s, oil prices hit bottom and Houston entered a recession. From 1982 to 1989, Exxon cut 40 percent of its national workforce—about 80,000 jobs, according to Steve Coll’s 2012 book Private Empire. Greenspoint suffered with Exxon; shops went out of business and apartments were poorly maintained.

Greenspoint’s layout may also have contributed to its slump. “Developers, for the first part, allowed too high a density,” said Wussow. “We always felt that 18 to 22 units was plenty, but some of those projects were developed with densities as high as 35 units per acre. That’s just too much. When you have an overbuilt condition, it tends to bring the whole apartment market down.”

The Greenspoint code from 1988 suggests “a density of 25-30 dwelling units per acre and clustered in foliated areas.” Today, Greenspoint’s curved boulevards with names like Imperial Valley are lined with garden-style apartment complexes, vast agglomerations of two-story buildings arranged around internal mazes of parking lots, some of their perimeters lined with razor wire. On street corners, people hold giant signs advertising move-in specials.

By the time Houston began to recover from the recession, Greenspoint had a reputation. Exxon’s white-collar paradise had lost its luster. In 1995, Exxon sold Friendswood’s residential properties and absorbed its commercial properties into Exxon Land Development, of which Wussow became president. An open letter from Friendswood Development’s then-president John E. Walsh published in the Bay Area Sun attributed the sale to “the company’s long-term strategy to focus investments on its core energy business.”

The titans of Texas development had disengaged, but visual traces of Exxon—its ideas about how people should live and work—would forever be cemented in Houston’s urban fabric.

Though the Greenspoint area remains a popular business center with no shortage of tenants, Greenspoint today is a remnant of a future that has already passed. Asked to describe Greenspoint’s architecture, Bart Baker, vice president of planning and infrastructure at the Greenspoint District, said, “Nothing comes to mind. It’s a nice product. There’s a little skyline out here.

It’s kind of its own little skyline out here.”

On a cold day in December, several couples strolled in a Greenspoint park named after Wussow. Blocks of apartment complexes used to stand on this 10-acre patch of green now dotted with gazebos. The apartments grew derelict and the Greenspoint District bought the property, demolished the apartments, and built a park in 2002. Wussow jokes that every Thursday he picks up trash.

Geonie Peterson, who has lived in Greenspoint for five years with her mom, was passing through the park on her way to a hair salon. “I like this park, but other than that, it just be ghetto. I don’t talk to nobody over here. They leave their trash everywhere, smoke, drink. There used to be a lot of fights here, but there needs to be more security guards. My apartment got broken into and the police said it’d take them a whole hour to get there. They just stole cell phones and stuff, but the police never came.”

As for the office towers overlooking the park, Peterson hasn’t given much thought to who or what is inside them. Her life is lived in run-down strip malls and bus stops, the remains of a once-world-class business district.

If this is Greenspoint’s present, how will Springwoods look in the future?

When asked, those close to the project had few specific attributes in mind, just vague hopes. Simon said he sees Springwoods becoming “one of many important urban centers” in Houston. Cagle said, “40 to 50 years is a little harder for me to project,” but “I want to leave this place better than I found it.”