Bad Credit: Are College Classes Working for High Schoolers?

A version of this story ran in the February 2016 issue.

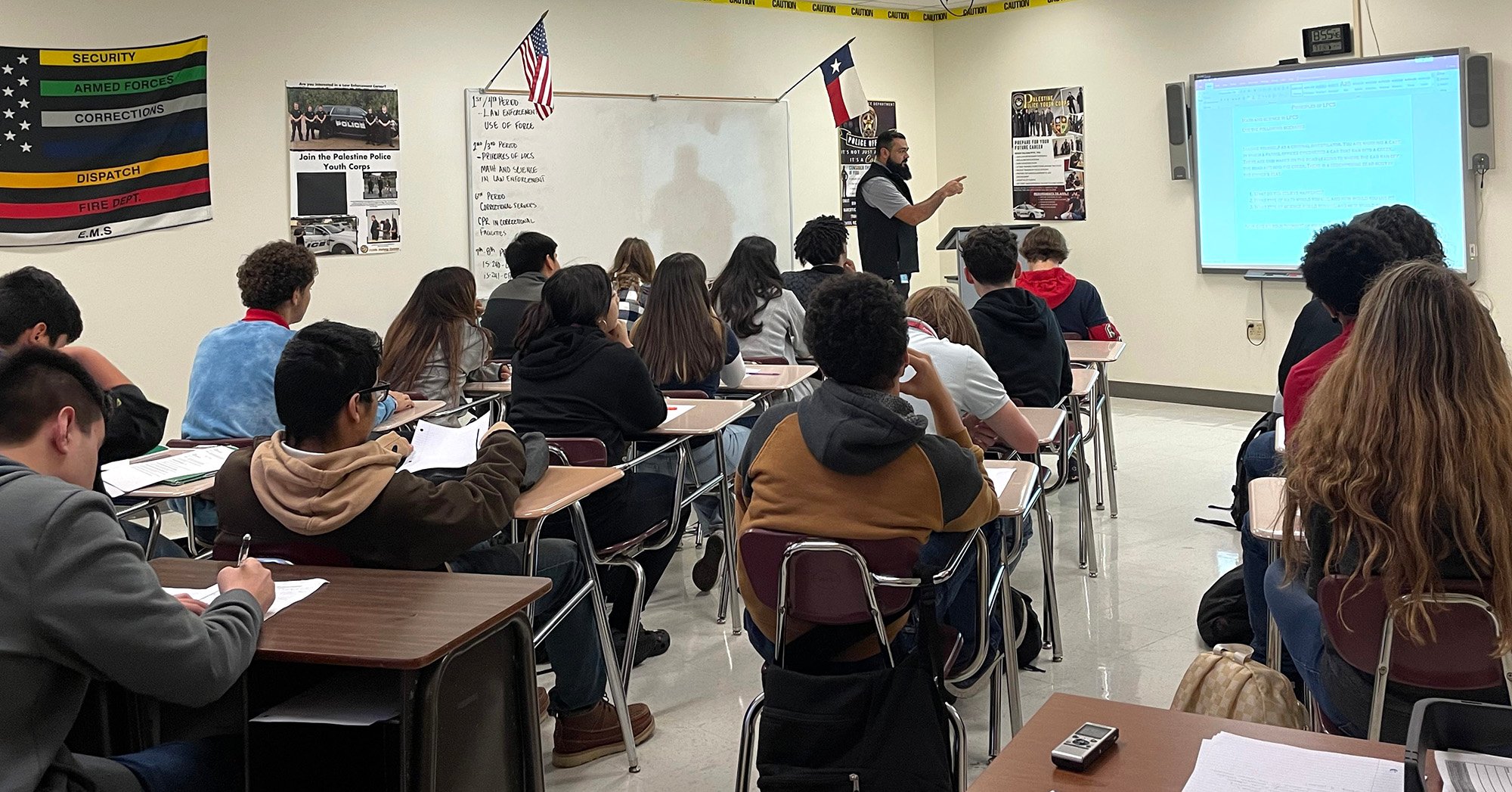

Dual-credit programs, which let students earn college-level credit while they’re in high school, are growing fast in Texas. Administrators say they help at-risk students build connections to an academic life after high school, and often earn college credit for free. Researchers have shown that such students are more likely than others to finish college, and finish it faster. Legislators like dual credit so much they’ve passed laws letting both high schools and colleges claim state funding for dual-enrolled students.

A decade ago, top administrators and lawmakers were more skeptical that all or most high school students could succeed in college courses. Now that momentum has shifted. Administrators in many school districts and community college systems have financial incentives and political pressure to grow their early college enrollment high, but some of the teachers who run the courses have begun wondering if the trend is growing too fast.

In the Rio Grande valley, El Paso and Houston — where early college programs are most prevalent — you won’t hear much opposition publicly. Ask if high school students are truly ready for college-level work, and administrators will answer with an enthusiastic yes. But some college faculty members disagree. Speaking with one another, they worry about making allowances for students who are still in high school — teaching an art course without nude models, for example — or answering to parents who expect to have a say in what their children discuss in school. High schoolers who enroll in college courses and do poorly could be saddled with a low GPA.

Such concerns rarely surface on the record. University of Texas-Pan American political science professor Samuel Freeman has been one of the rare critics to speak up consistently. Speaking with PBS NewsHour in 2015, Freeman explained his worries about opening college courses to most high school students. “The vast majority of them are not ready emotionally or intellectually,” he said.

In El Paso, where early college programs have spread to eight schools, some college instructors have begun raising concerns too. In the last six years, more than 1,000 students have advanced from high school to El Paso Community College and on to the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). Some instructors there worry that they’re receiving students without the requisite skills.

The problem isn’t that high schoolers “aren’t ready for college,” says UTEP graduate student Eddie Nevarez, but rather that they get credit for courses that don’t prepare them for upper-level college work. He laid out his concerns in an op-ed published by the El Paso Times in December.

The dual-credit courses offered in El Paso high schools in lieu of a first-year college composition class leave students “without the skills needed to write a cohesive paper,” he wrote. As a teaching assistant in the English department, Nevarez says he’s worked with students whose dual-credit courses during high school left them ill prepared. In particular, he says, the college-level courses taught in high schools need to be updated to match the evolving focus on digital literacy that UTEP has embraced.

“I’m not saying dual credit in this region is bad or anything. I’m just saying it needs to be changed,” he told the Observer. “What are the flaws in this system, where you give them the opportunity to go to college but you’re not really preparing them?”

Joanne Peeples, math coordinator at the El Paso Community College Transmountain Campus, oversees the college-level math instruction for El Paso high schoolers earning dual credit. When those courses are taught on high school campuses, she says, it’s tougher to guarantee that students really are being taught college-level material. Her classroom visits are announced, she says, so there’s no element of surprise to her observations. Still, she says, the college-level coursework at high schools is “definitely not up to snuff, in some cases.”

El Paso ISD’s enthusiasm for expanding its early college program has also put some pressure on high school principals to show high rates of dual credit enrollment, she says. “They are just working the system, some of the principals. They put some people in the courses that really shouldn’t be in there.”

Like Nevarez, Peeples worries that students are being ill-served by courses that are too much like other high school work, that don’t force students to have the independence and responsibility expected in a college atmosphere. Without those things, she says, “You’re not getting the skills you need to survive at a university.”