Don’t Fence Me In

The invention of barbed wire in 1874 marked the end of the open range in America’s West, and the 20th century ushered in settlers who sought security rather than adventure. The Wild West became tamer, more homogenized. Still, pockets of insurrection, physical and philosophical, remain in the West, defying conventionality and containment. Two recent books—one about an iconoclast, another about an icon—celebrate the value and tenacity of the free-range way of life.

A working subtitle for Steven Davis’ biography of J. Frank Dobie could have been “My Way.” Dobie, the first Texas-based writer to gain national attention, lived life on his own terms and often demanded lots of elbow room.

Born in 1888 in the Brush Country of South Texas, Dobie spent his childhood working on the family ranch, learning how to ride horses and herd cattle. He loved the gritty authenticity of cowboy life, but he also wanted to pursue his education. He left the ranch and headed to college in New York, where he fell in love with literature, particularly the Romantic poets, with whom he shared a reverence for the land. In 1914 he returned to Texas as an English professor at the University of Texas at Austin. There he cultivated a reputation as a cowboy professor, donning khakis and boots instead of natty tweeds, outfitting his office with cowhides and defiantly refusing to pursue a Ph.D., which he feared would “sap his vitality.”

Though Dobie was passionate about scholarship, he felt ill-suited to the ivory tower and railed against what he saw as a rigid bureaucracy. Unable to shake the pull of the Texas backcountry, he felt like a misfit and a failure. “While I am in one world, it is forever my fate to hear the music of the other,” he wrote to his wife. “In the university, I am a wild man; in the wild, I am a scholar and a poet.” This tension would result in Dobie’s greatest accomplishment—making regionalism a valid area of study by introducing Southwestern folklore into the canon.

Dobie was introduced to folklore sitting around the campfire on his family ranch, listening to vaqueros tell stories. These were folktales of life on the range, passed down orally by generations of storytellers gathered around campfires and kitchen tables throughout the Southwest. Dobie saw these narratives as a way to marry his passion for literature with his love of the land. The cowboy had become his muse, their stories his medium.

Davis writes admiringly of Dobie’s pioneering work in folklore, but his biography is no valentine. Calling Dobie’s literary legacy “uneven,” Davis suggests that Dobie’s books, written in anecdotal style, are “best read in bits and pieces, in between chores.” (Given the amount of time the biographer spent on this project, you can imagine how clean his house must be.)

Davis is more intrigued with the man than with the material; the real story here is Dobie’s philosophical evolution from a fierce, provincial nativist to a fiery progressive.

As a young man, Dobie embraced rugged individualism and brandished a fierce regional pride. Surprisingly, his brief stint at Columbia University in 1913 heightened his defenses. As immigrants and minorities gained an increasing foothold in the country and industrialization grew, Dobie felt his way of life was besieged.

His thinking started to change in his late 40s, when he became friends with a group of Austin liberals who met at Barton Springs, swim trunks and all, to hash out ideas—Austin’s version of a literary salon. Dobie was invited in 1943 to be a visiting professor at Cambridge University. There, writes Davis, he was “ripe for evolution” and “threw off the shackles of Texas provincialism … no longer whooping and hollering on behalf of Texas. Instead, he came to serve as the state’s chief critic.” By the time Dobie reached his 50s, he had concluded that the greatest threat to individual freedom was not government, but right-wing business interests.

An early prototype for figures like Norman Mailer and Kinky Friedman, Dobie was compelled to join public discourse. Using his syndicated newspaper column as a megaphone, he argued against McCarthyism, political cronyism, the UT Board of Regents, and censorship at the university. He fought for integration, the labor movement and women’s rights. The university fired him, newspapers dropped his column, and the FBI investigated his Communist sympathies. Dobie reveled in the firestorm, which strengthened his resolve. Years later, Lyndon Johnson awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Davis, a curator at the Southwestern Writers Collection at Texas State University in San Marcos, where Dobie’s archives reside, writes with authority and ease. At times, however, the prose feels flat and the reader wishes for more wit and verve, particularly given such prime material.

Dobie died on Sept. 18, 1964, leaving a staggering volume of work—nine books, over 800 articles, 1,300 columns—as well as a vibrant community of Southwestern writers. As Davis writes, Dobie’s greatest achievement was his “refusal to accept himself as a finished person.”

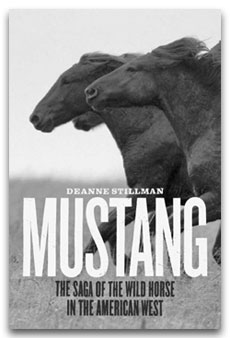

If Davis’ biography celebrates a liberated life, then Deanne Stillman’s book is a plea to save thousands of others. In Mustang, Stillman traces the origins of America’s most beloved icons and makes the case for their urgent liberation.

It is difficult to get through the first chapter of Mustang, in which Stillman recounts the horse’s terrifying trip to North America on the ships of the Spanish conquistadors. If the ships became too heavy, sailors would throw horses overboard to lighten the vessel and catch air in the sails. For the sake of a drifting ship, countless horses were frightened from their quarters, forced to walk the gangplank, and left to drown in the ocean. (A particularly windless part of the sea gained the notorious title “horse latitudes.”) Stillman’s opening scene sets a sobering mood for the book—a riveting, thoroughly researched odyssey of the horse and its place in American history. It also introduces what Stillman calls the great paradox of the horse: “It possesses a wild spirit but serves as the greatest helpmate this country has known.” The horse serves man, sometimes even in death.

Scientists have traced the horse’s origins to North America, but various epochs left it nearly extinct from the continent. In the 16th century, Spaniards brought horses home, employing their strength to wipe out empires. After conquering the Aztec, Cortes attributed the victory “to God and to the horse.”

By the 1700s, mustangs proliferated in the American West, and it was not uncommon to see bands of 3,000 or more roaming the Great Plains. Some maps of Texas distinguished regions by their horse populations; one was labeled “simply Wild Horses,” and another as “Vast herds of Wild Horses.”

More than any other group, Native Americans were transformed by the arrival of the horse, which they considered a brother, a partner and a kindred spirit. With the horse’s help, tribes could cover more ground, kill more buffalo and increase their leverage with traders. In one of the most famous horse trades in history, Lewis and Clark traded trinkets and an American flag for horses from the Shoshone Indians, saving a stalled expedition. The era of the cowboy and his cattle drives made mustangs synonymous with the Wild West. Hollywood would later solidify—and sensationalize—the horse’s reputation in westerns.

Stillman’s account of the horse and its prized place in American history stands in contrast to its diminished, even damaged, reputation today. Because the wild horse has no natural predator, man must grapple with its population control. The ranching lobby—ever conscious of its grazing rights—presents the horse as feral, violent and destructive. Mustangs are left at the mercy of elected officials and the Bureau of Land Management. The horses are in constant danger of sudden roundups, after which the lucky ones are sent to sanctuaries and the unlucky ones sold to become pet food. Other horses have been murdered out of bloodlust, sport or senseless rage. In the wake of a 1998 massacre outside of Reno that killed 34 wild horses, Stillman wrote: “Almost five hundred years after Cortes traveled to the New World, we are still throwing them overboard, into the horse latitudes, trying to lighten our load.”

Stillman’s arguments are persuasive. At times, she lets her imagination fill in gaps when history is silent, an unsettling practice that projects what the horse saw, smelled and sensed onto the page. In small doses, this enriches the reading experience, but ultimately feels uncomfortable, wedged between historical facts. Overall, Stillman proves a thoughtful guide whose passion for the mustang is inspiring and infectious.

In one of her more heartbreaking accounts, a captured mustang dies in captivity for no other reason than a broken spirit, its moans haunting the Great Plains. You don’t have to be an equestrian or history buff to realize these magnificent animals deserve all the open space we can give them.

A former editor at Random House, Kirk Forrester is a freelance writer based in Austin.