Cultivating Creativity

NULL

Our environment has always shaped our artistic undertakings. In Africa, elaborate wooden masks and sculptures come from the west, where rainforests dominate. On East Africa’s savanna, wood is a precious commodity, so the arts focus on jewelry, clothing and body modification.

In Texas, folks frequently lament a cultural landscape as desolate as the scrublands of Amarillo. But two exhibits in Houston address how location and settings influence creativity, and one in particular tries to turn lemons into lemonade.

No Zoning: Artists Engage Houston makes the argument that Houston’s lack of land-use and zoning ordinances has created a unique environment for the city’s creative class. “In this often chaotic, jarring urban topography, many Houston artists have been able to carve out spaces and opportunities for themselves, their work and their communities,” the curators say in introducing the show at the Contemporary Art Museum–Houston.

Visitors to the gallery are initially confronted with an egg-shaped excision from the interior of a condemned house. The ovoid structure looks as if someone took a giant melon-baller and carved it out of the inside. The cutout includes several rooms, doorways and even a small piece of the roof. The work by Dan Havel and Dean Ruck builds on the idea of creating art from found objects, in this case an old house.

Visitors to the gallery are initially confronted with an egg-shaped excision from the interior of a condemned house. The ovoid structure looks as if someone took a giant melon-baller and carved it out of the inside. The cutout includes several rooms, doorways and even a small piece of the roof. The work by Dan Havel and Dean Ruck builds on the idea of creating art from found objects, in this case an old house.

Marcel Duchamp pioneered using common objects to create art. He caused a stir in 1917 when he plopped a urinal down in a gallery, painted “R. Mutt” on it and called it Fountain.

In the same vein, Bill Davenport built a kiosk inside the Houston museum called Bill’s Junk. Davenport sells what he calls “things people made, but didn’t want anymore.” The artist sits behind a cash register, and everything is on sale, including Davenport’s diploma from the Rhode Island School of Design for $32,000.

For another item, Davenport has taken a slice of a tree branch and stuck a rusty hunting knife into it. He calls it Monument to Masculinity and offers it for $150.

The exhibit, though, fails to clearly tie the art on display to the lack of zoning. But an informal poll of Houston’s art community—taken at a cocktail party, of course—produced much-needed clarification.The most common explanation is that Houston’s unique ugliness challenges conventional ideas about what a city should look like, and therefore releases the creative juices. They also say that artists have taken advantage of the city’s laissez-faire planning to create creative spaces where other cities would have denied them permission.

The best proof of this hypothesis is found outside the gallery, and the curators direct the adventurous to explore the city.

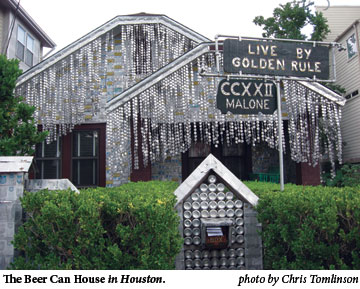

One location is The Beer Can House in the Washington Avenue neighborhood, a nationally recognized example of American folk art. The modest bungalow looked like all of the others on Malone Street until 1970, when owner John Milkovisch began contemplating uses for the prodigious number of beer cans he was accumulating. A retired upholsterer for the Southern Pacific Railroad, he decided to unroll the aluminum cans and cover his house with them.

Milkovisch also began experimenting with curtains made from beer can lids and pull-tabs that he could hang from the eaves. Before he died, he estimated he went through 50,000 beer cans. Texas Pride and Lone Star were apparently his favorite brands.

A more conventional look at artistic influences can be found at The Menil Collection, a museum in central Houston. Visiting Witnesses to a Surrealist Vision is best described as going into your crazy, globetrotting aunt’s attic. This “room of wonders” is filled with 200 objects that inspired surrealist artists, including items that were found in their studios. The room is creepy and explains a lot about the museum’s world-famous surrealist art collection.

Frightening masks from around the world hang from the walls, and a mannequin wearing a body suit of black needles stands in the center of the room. A display case is chock-full of the macabre; a child’s iron death mask is perhaps the most eerie.

Picasso was an avid collector of African art, and seeing his paintings next to the masks proves that Congolese sculptors were truly the first cubists. A more important lesson, though, is the surprising similarities between the death mask from France, the war mask from Mali and the ceremonial masks of Polynesia and the American Northwest. They argue against the idea that special places and settings inspire unique artistic visions. They make the case, instead, for a common human vision.