Why Don’t Texans Vote?

The poor and marginalized stay at home, while the rich and powerful cast their ballots.

By now it’s a familiar, even worn-out, storyline: In 2008, a surge of new and newly-energized voters helped propel Barack Obama into the White House. Voter turnout was the highest in 40 years. But in Texas turnout actually dropped to 56 percent from 2004’s 57 percent. Texas has ranked near the bottom of the states in voter turnout for years.

In mid-term elections, engagement is even weaker. In 2006 Rick Perry faced three gubernatorial challengers and the Democrats took control of the U.S. House and Senate. Yet over 1,000 Texas precincts had less then a quarter of registered voters show up. Statewide turnout was a dismal 38 percent, worse only than Utah and West Virginia.

Sure, there were polling places overrun with voters in November 2008. Take George W. Bush’s precinct in the Preston Hollow neighborhood of North Dallas. Precinct 1116 had a turnout of 84 percent (almost 2:1 McCain.) Or how about Rick Perry’s precinct in his $10,000-dollar-a-month mansion in upscale West Austin? 84 percent too. Or, Bill White’s precinct in the gated Stablewood community in Houston? 81 percent. One precinct in the white middle-class suburb of Allen had an incredible 99 percent turnout. Of 908 registered voters there, 896 punched a ballot. Three-quarters voted for McCain.

In fact, of Texas’ 8400 precincts over 1400 had a turnout of 80 percent or more for the presidential election.

On the other extreme are pockets of severe disengagement. Border communities and poor, minority neighborhoods in big cities have especially low registration and turnout rates. Six of the seven precincts in Presidio County – one of the poorest counties in the nation – had fewer than half of the registered voters come to the polls in 2008. One barely topped 23 percent.

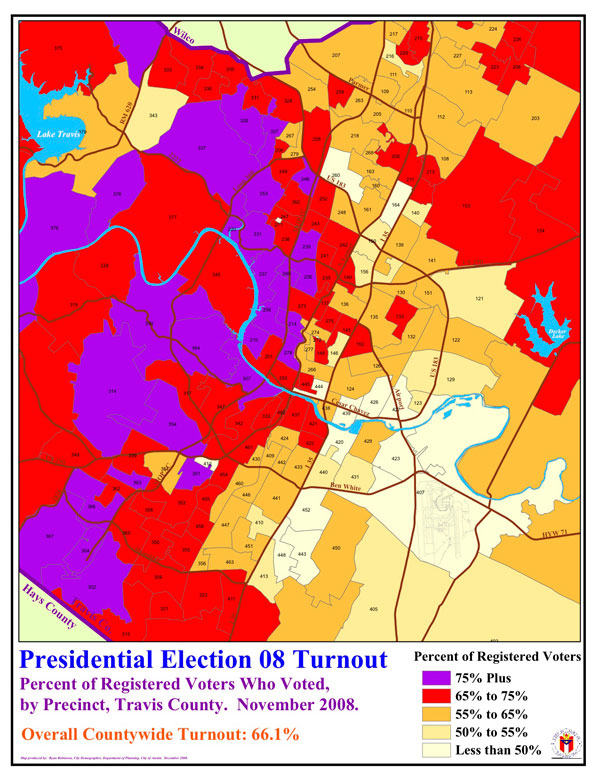

Even in Travis County, which frequently posts the highest urban turnout in the state, there is a stark contrast. The more affluent sectors of Austin largely vote, and the historically black and brown East Side largely don’t.

Decades of political science tells us that income, education, ethnicity, age and a history of voting are the best predictors of whether someone will vote. If you’re poor, young, not white, and lack a college degree, chances are you’re not going to the polls. This is a fact of American political life that’s changed little in the last half-century. Unlike in Western Europe, where there is little drop-off in voting rates as you move down the socio-economic ladder, the U.S. electoral system has a chronic “class bias.” But the disparity is not unmovable – even small swings can sometimes change outcomes for candidates, parties, and people.

Texas may have one of the most lopsided electoral landscapes. Perennially low turnout among the state’s booming Latino population is one of the chief reasons that Democrats have failed to take a statewide office since 1994. Compared to other states with large Hispanic populations, Latino electoral engagement in Texas lags considerably. In 2008, 54 percent of Hispanic citizens voted in New Mexico. In California, 57 percent turned out. In Texas, the figure was 38 percent, much lower than the national average of 50 percent.

John Sides is a political scientist at George Washington University who’s studied non-voters in America. In a paper published in 2008 called “If Everyone Had Voted, Would Bubba and Dubya Have Won?,” Sides explored through statistical modeling whether universal turnout would have changed presidential election outcomes. His answer: only in extremely close elections like the 2000 Gore-Bush match-up. Non-voters in most states are only slightly more Democratic than voters. However, there was one significant exception to the rule: Texas. Latinos in Texas tilt heavily Democratic but they don’t vote. Sides postulates that the primary factor may be the health of the state Democratic Party and the attractiveness of the candidates.

In Texas, “the Democratic candidates are not that viable,” Sides said. “There’s less that’s motivating Democrats to turn out and vote so the non-voter population becomes disproportionally Democratic.”

Another problem is a lack of sustained investment in voter registration and get out the vote (GOTV) drives, says Crystal Viagran, Hispanic GOTV director for Travis County and precinct chair for one of the lowest turnout precincts in Austin.

“We’ve always been treated quick and dirty,” she said of Latinos. “We have such high Democratic performance that we often only get a mailer or a phone call or somebody drops a piece of lit on your door.” Viagran said the consultants that run campaigns are stuck in a “vicious cycle.” They put little to nothing in low-income, minority neighborhoods; get little back in return; and so chase votes in more reliably high-turnout communities. Laura Barbarena, a San Antonio-based political consultant who specializes in Latino outreach, agrees. “They’re going to go after those precincts that have high voter performance,” Barbarena says. “Again, it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s much easier to get somebody to vote who’s voted before than somebody who’s never voted.”

Minimal competition in minority-dominated districts has also induced voter apathy, Viagran said.

“It’s just a cycle and it’s not going to change until we change that attitude,” she said. Depressed turnout in working class and minority areas makes it that much harder for statewide candidates to overcome the Republican’s edge.

“If we could increase turnout by 15 to 20 percent in minority communities I think we could win handily,” Viagran said. “But because this has gone on for so long it’s hard to get buy-in from the community when you show up a month before the election.”

Barbarena uses the analogy of a pie to explain how political campaigns approach vote-getting: Either they go after certain slices of the electoral pie, individuals with a history of voting or likely voters. Or, they try to grow the pie by seeking new voters.

“Tony Sanchez lost on the presumption that he was going to make the pie bigger,” Barbarena said of the Democrats’ 2002 gubernatorial nominee.

Still, statewide Democratic candidates will need to drive up the numbers of Latino voters to stand a chance of winning – and that includes Bill White, Barbarena said. “Bill White needs the Latino vote to win but he’s not going to spend his money to get the Latino vote out,” she said. Barbarena said she was shocked to see White TV spots in San Antonio calling for more border security.

“It’s like, dude that’s not going to go over well with Latinos,” she said. Instead, candidates, including White, need to be “talking about the issues that matter to Latinos. Duh.”

Although they don’t make headlines or receive much support from Democratic Party insiders there are efforts underway across the state to turn out the working-class and minority vote. One of the biggest campaigns is an all-volunteer effort organized through the Industrial Areas Foundation, a community-organizing network with dozens of affiliates in Texas.

Moses Robledos, a deputy sheriff and member of Valley Interfaith, is helping to get 50,000 voters to the polls in Hidalgo County, one the lowest turnout counties in the state. Why do so many people choose not to vote in his area?

“Generally they don’t feel that voting is important especially when you’re talking about candidates,” Robledos said. “They don’t have an interest in the candidates.” It’s the issues they care about – health care, job training for adults, and immigration. Although Valley Interfaith and the voter drive is non-partisan, Robledos said they’re raising awareness about how the looming $18 billion budget crisis will affect working class families

“The budget crisis is being corrected – it seems to us anyway – on the backs of our children,” Robledos said. “We see that as a great wrong.” When the Texas Legislature convenes in January, Robledos hopes that increased turnout among low- and middle-income Latino voters will earn them a seat at the table. “That’s what it’s all about,” Robledos said.