Life On the List

A single mistake when he was 12 landed Josh Gravens on Texas’ sex offender list. He’s been paying for it ever since.

A version of this story ran in the June 2012 issue.

When Josh Gravens was 12 years old, he made a terrible mistake. He and his sister, who was 8, had sexual contact, twice. “Like, where my body part touched her body part,” he says. “It was never penetrative. Obviously, it couldn’t have been what they call consensual, but it was playing.”

Josh’s sister told their mother, who was alarmed. She wanted to ensure that, even if Josh’s intentions were only curious, he learned appropriate behavior right away. She called a Christian counseling center near their home in Abilene and described what happened. She was informed that, by law, the center had to report Josh to the police for sexual assault of a child.

The next day, Josh was arrested and sent into Texas’ juvenile justice system. He wouldn’t get out for three and a half years.

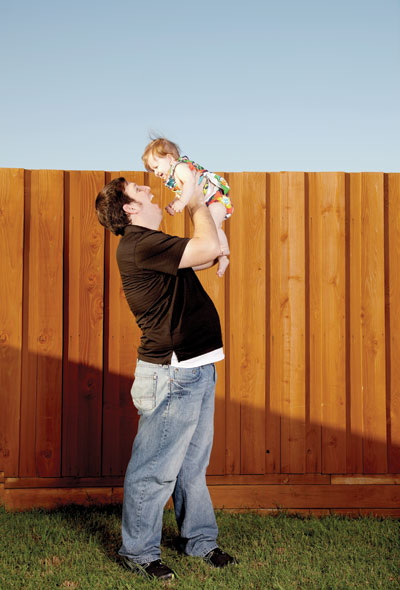

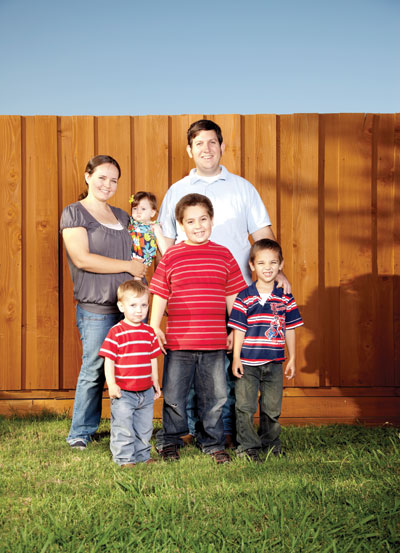

“My family didn’t want to press charges,” he says. “The state took up the case and pressed charges.” Josh and I met earlier this year at his older sister’s house in Plano, where he lives with his soft-spoken wife Nicole and their four children, two from Nicole’s first marriage and a toddler and infant with Josh. The three-bedroom house is neat but crowded, full of happy kids, two big dogs and a couple of turtles in terrariums.

“There was quite a bit of shock,” Josh says of his arrest. “My mother didn’t understand at the time that if the counselor felt there was a chance it could happen again or there was something going on, she was obligated to report it.”

That phone call, and the child’s choice that prompted it, unalterably changed the course of Josh’s life.

Today he is 25. He and his family are living with his older sister and her husband while Josh looks for work. He estimates that he’s applied for 250 positions since January, when the checks from his job at a Christmas tree lot started to bounce. He stays upbeat, though finding work is harder for him than for other people. Because of what he did when he was 12, Josh is a registered sex offender. He’ll remain on the list until he’s 31.

Unlike some states, Texas lists juveniles, and adults who committed their crimes as juveniles, on its public sex offender registry, a searchable website run by the Texas Department of Public Safety. The registry lists each offender’s name, birth date, current home address, current employer and work address, and any school being attended or occupational license held. Also listed are the offender’s sex, race, ethnicity, height, weight, hair color, eye color, shoe size and shoe width. The website keeps an up-to-date color photo of each offender. If Josh gets a haircut or grows a beard, he’s supposed to go back to the local DPS office and re-register to keep his image current.

The day before I first met Josh, two officers from the Plano Police Department had dropped by unannounced to make sure Josh really lives where his registration says he does. They also wanted to see his blue card, an ID card registered offenders are required to carry at all times. I asked Josh if he felt harassed by that. “You could,” he says, “if you weren’t used to it.”

Not only does Texas list juveniles, but it has no lower limit on the age of registerable children. Right now, Texas lists a 12-year-old. Twelve is too young to have a Facebook account, but with a quick search I can find this boy’s home address in a small town in Central Texas. He has brown hair and blue eyes, is 5 feet 2 inches and 102 pounds. His photograph shows flushed cheeks and a worried brow. No school is listed, perhaps because he is prohibited from attending school, as many sex offenders are. He moved here from North Carolina, where he was adjudicated for “indecent liberties between children.” He’ll be on the list until 2021.

Josh admitted what had happened with his younger sister from the beginning and was adjudicated for one count of aggravated sexual assault. (Any sexual assault against a child under 14 is considered aggravated.) In error, though, his DPS page also lists his youngest sister, age 6, as a second victim. Josh and his mother say Child Protective Services listed the second child on its original complaint, but the judge found the allegation lacked merit and struck it out. Josh says there was no such assault, he wasn’t adjudicated for it, never pled to it, but hasn’t had the money to petition to have it removed. (Despite all the public information about Josh available on the Internet, his court records, being those of a juvenile, are sealed. Josh’s story here is based on extensive interviews with him and his wife. Major points have been corroborated by family members.)

Josh says he never considered denying the abuse. “I thought it was so important that I never call my sister a liar,” he says, “which is what happens in a lot of cases, and [the victim] has to deal with it later on. I never wanted that to happen to my sister. I did value telling the truth more than freedom, I guess, because what’s the point of freedom when you have to live a lie?”

Josh understood the destructive power of secrets because he had one of his own. Between the ages of 6 and 8, Josh says he was repeatedly raped by three neighborhood high schoolers—a babysitter and her two male friends. “They said they would kill my sisters and my parents if I ever said anything,” Josh says. “And I held them true to that, because they were big into hunting, big gun people. Every Saturday they were out shooting. I went on with my life and kept that in the back of my head, but obviously it messed me up.

“Everything that I did with my sister came directly from the things I had experienced in the abuse,” he says. “I was sexually confused, and it started to play out with my sister.”

Josh was imprisoned in the Texas Youth Commission (TYC), where he says he was bullied for his age and crime. “I was only 13, by far the youngest,” he says. “I’d be marching in line when we were going building to building, and I’d have to endure the person behind me punching me square in the kidney the entire time. You could hear it. The guard would look, but he wouldn’t see anything.”

He never told anyone that he had been abused. “I was so embarrassed by it that I only started talking about it last summer. [In TYC] I never felt safe enough to talk about what had happened to me in childhood,” he says, “especially since they’re looking for any possible reason you might re-offend.”

One little-realized fact of sexual abuse is that more than a third of sex offenses against children are committed by other children. In 2009, the U.S. Department of Justice published a comprehensive bulletin about child-on-child sex abuse that analyzed multiple studies. It found that about half of juvenile sex offenders are between 15 and 17, the age people might expect offenders to be. But many are much younger. More than a third are between 12 and 14, like Josh was, and one in 20 is younger than 9.

These children are also not generally being convicted of the crimes people associate with sex offenders, like rape. Almost two-thirds of offenses were for fondling or non-forcible offenses like sharing pornography. But they all are sex offenders under the law.

Dr. Paul Andrews is a forensic psychologist who works with juvenile sex offenders in Smith County. He said labeling children sex offenders is becoming more frequent—and the offenders are getting younger. “Here in the last couple of years, we’re seeing kids as young as 10 being adjudicated for their sexual misconduct,” Andrews said. But he speculates that this is because of increased prosecution of young children, rather than increased misbehavior.

Children Josh’s age and younger “are usually exploratory, curious,” he said. “They do not have any kind of predatory tendencies, usually. They’re not budding sexual molesters. They’re kids who are curious and sometimes not well-supervised, having been exposed in places to sexual material. Without good sex education—‘Don’t do this, this is going to get you in trouble’—they sometimes cross that line and suddenly they’re in the criminal system.”

Josh was transferred to the Bill Clayton Detention Center in Littlefield in November 2000. The Clayton unit housed younger offenders and had a specialized sex offender treatment program. Josh says the treatment involved things like “coping skills, like how to handle an erection when you’re around a child. That’s an interesting topic, because that was never the case. A pedophile is a person who’s attracted to the prepubescent male or female form. In a lot of our cases, we were curious about sex, and a sibling was nearby, and we weren’t necessarily attracted to them, but they were there. That’s not to justify it, but very seldom was it someone who went and attacked some stranger. We didn’t want 8-year-old girlfriends or anything like that.”

The Justice Department study confirms Josh’s observations about juvenile sex offenders. It found that less than 3 percent of victims were strangers to their assailants, while a quarter were family members.

The conventional wisdom about sex offenders is that if they do it once, they’ll do it again. That’s the whole logic behind having a registry. But statistically, sex offenders are less likely to re-offend than other kinds of criminals, and juvenile recidivism is even lower. A 2006 study of 300 registered sex offenders in Texas who were juveniles at the time of their first offense found that just 4.3 percent were arrested as adults for another sex crime.

Yet youths like Josh, with a very low chance of re-offense, are listed publicly alongside dangerous predators. As of March, Texas listed 4,784 offenders who were 16 or younger at the time of their offense. Twenty-eight of those on the sex offender registry are still children. And unlike their peers who commit assault or even murder, these adolescents’ crimes will follow them into adulthood.

Josh was 16 when he got out of TYC. That’s when his photographs began to appear on the DPS website, leading many who research him to think he was older when he offended. Josh was released into his parents’ home, with his sisters, but had to have alarms on his doors and windows that would beep in his parents’ room when opened. He smiles. “I didn’t mind; I was out [of TYC].”

Josh was 16 when he got out of TYC. That’s when his photographs began to appear on the DPS website, leading many who research him to think he was older when he offended. Josh was released into his parents’ home, with his sisters, but had to have alarms on his doors and windows that would beep in his parents’ room when opened. He smiles. “I didn’t mind; I was out [of TYC].”

Josh attended the local high school, where he quickly made up for lost time. He joined the math and science University Interscholastic League teams, the Academic Challenge, and the prom committee. At the house in Plano, he leads me to the kitchen table and opens a folder fat with certificates and commendations. There are awards for calculus and desktop publishing, a contest-winning speech for the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and notifications of scholarships from a local power company and Southwestern Bell. His classmates voted him “Friendliest Boy.”

But two weeks before graduation, everything changed. The local paper ran a story about sex offenders. “Usually, your life is pretty peaceful,” Josh says, “until something comes out in the newspaper about sex offenders. Then everybody gets up in arms and they go on the DPS website and check their ZIP code. Emails start passing around, ‘Oh, do you know who’s on the list?’” Josh didn’t see the article, but “I felt like something was up. I didn’t know what it was. Out of the blue, people started asking what my middle name was.”

Soon everyone knew. He lost friends; people started ignoring or avoiding him, including teachers. “I just couldn’t wait for graduation,” he says. “I love school. I’ve always liked to learn and read. But the last two weeks were horrible. I couldn’t wait to get out of there.”

Josh graduated seventh in his class and attended Texas Tech University for political science, his tuition fully covered by scholarships and grants. He took 19 hours his first semester, which together with the Advanced Placement credit he’d acquired in high school, made him a sophomore by his second semester. He also worked for the National Ranching Heritage Center, taking care of old buildings, and served on the residence hall senate. But his peace was short-lived.

A local TV station broadcast a story on sex offenders and included a picture of Josh. “I wasn’t contacted about it. Obviously it’s public information so they just went ahead and ran the story. But that’s when the death threats started.”

First, an anonymous handwritten note appeared under his door telling him to leave the school or be killed. Josh didn’t report it because that would have called attention to his registry status. He was still hoping few people knew.

But the word was out. “It was a Friday night, probably 11 p.m.,” he says. “I was in the parking lot and this truck drove by and started throwing beer bottles at me. I had to run inside. They yelled, ‘Get out of our school, you child molester! I wish I could kill you!’”

While meant to be a resource for parents, the sex offender registry can also be a resource for vigilantes. In 2004, Lawrence Trant of New Hampshire tried to kill several registered sex offenders, stabbing one and setting fire to two apartment buildings where seven offenders lived. From prison, Trant told the Boston Globe, “I hope I’ve done a service to the community.” In 2006, Canadian Stephen Marshall flew to Maine, wrote down addresses for 29 of the 34 sex offenders on the state registry and went on a murderous road trip, visiting the homes of six offenders, killing two.

After being chased by the truck, Josh was so afraid that he stopped leaving his dorm except for classes. Finally, he dropped out.

Sex offender registries are a fairly new law enforcement tool. In 1994, a 7-year-old girl in New Jersey, Megan Kanka, was raped and murdered by a neighbor who had previously been convicted of child molesting. Within days of Megan’s death, her parents began lobbying for residents to be notified when a sex offender moves into the neighborhood. Only a month after the murder, the state Legislature rushed to pass a set of bills to register and track offenders, and notify the community when one moves in nearby.

“I’d rather err on the side of potential victims,” Steven Corodemus, a Republican in the New Jersey General Assembly, said at the time. “We can lock away these animals and take out of our minds the doubts that our children will be the next victims.”

But research hasn’t shown that to be true. Most victims of sex crimes know their assailant, and most assailants are first-time offenders, who wouldn’t be registered. But even concerning convicted, registered sex offenders, the most thorough study of Megan’s Law, as the community notification statute was called, concluded that it simply didn’t work.

In 2008, a study sponsored by the Justice Department looked at crime in New Jersey during the 10 years before and 10 years after Megan’s Law was passed. Its findings include: “Megan’s Law has no effect on community tenure (i.e., time to first re-arrest); Megan’s Law showed no demonstrable effect in reducing sexual re-offenses; Megan’s Law has no effect on the type of sexual re-offense or first-time sexual offense; Megan’s Law has no effect on reducing the number of victims involved in sexual offenses.” The study concludes, “Given the lack of demonstrated effect of Megan’s Law on sexual offenses, the growing costs may not be justifiable.”

Efficacy aside, the sex offender registry and notification laws are intuitively appealing in a way that likely makes them permanent. Many people want to know when a sex offender moves in nearby. In that case, critics argue the registry should be reserved for only the very dangerous, those who are likely to re-offend.

As of May, Texas’ sex offender registry lists more than 70,000 people. Critics contend that the sheer size of the list is counter-productive, because it shields the truly dangerous sex offenders in a crowd of people who will likely never commit another crime.

Torie Camp is deputy director for the victims’ rights group Texas Association Against Sexual Assault. She’s one of many who say the size of the registry makes it less useful and less fair. “The registry currently treats every single sex offender like they were all the same type of offender,” she said, “and with 70,000 people on that list, they’re not. There are some very dangerous people on that list and there are some people who aren’t very dangerous and don’t need to be listed. I would say that includes juveniles. From the research we’ve seen, juvenile sex offenders are the best target group for rehabilitation, and they do not necessarily pose a threat to the same extent as adult sex offenders. I would even argue that there are many adult sex offenders that, having them on the list just scares people in a community. It doesn’t make them any safer.”

Camp added another common criticism, which is that the registry creates a false sense of security. “Our research shows that 18 percent of sexual assault survivors actually make a report to law enforcement,” she said. Far fewer than that result in a conviction, so Camp said while the Texas list is enormous, most people who have committed a sexual assault aren’t on it. “Everybody has sex offenders living in their neighborhood,” she said. “Just some of them are on the registry and some are not.”

But instead of refining the list, sex offender laws keep expanding it. Less than a month after New Jersey passed Megan’s Law, the U.S. Congress passed the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act, mandating that each state keep a registry of violent sex offenders against children accessible by police. In 1996, the Megan’s Law amendment to the Wetterling Act made these registries public and required community notification when sex offenders moved in. In 2003, another bill created a federal sex offender registry that comprises all 50 state listings. Meanwhile, most municipalities have established “child safety zones,” which are areas around schools, churches and parks where sex offenders cannot live. Many schools ban sex offenders, and property owners won’t rent to them. Some states don’t allow sex offenders to use the Internet, to prevent them from contacting minors. But this also means they can’t search for jobs or pursue an online education.

In 2006, Congress passed the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act, the first part of which was the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA). The law broadens which crimes deserve registry and extends registration to children as young as 14. Sexual crimes against children are an automatic lifetime registry, so most juvenile offenders convicted under SORNA would be sentenced to the sex offender registry for the rest of their lives.

The deadline to implement SORNA was July 2011. Many states balked at its implications for juveniles, and Texas was one of them. In an August letter to the Justice Department, Gov. Rick Perry’s chief of staff wrote, “In dealing with juvenile sex offenders, Texas law more appropriately provides for judges to determine whether registration would be beneficial to the community and the juvenile offender in a particular case.”

But Texas has harsher laws against juvenile sex offenders than many states, even without SORNA. Other states don’t list juveniles, or they keep their juvenile lists accessible only to police, or they don’t sentence juveniles to registration that extends past their 18th birthday, or they at least have a floor on how young a person can be publicly registered. Texas does none of this.

Rather than rejecting SORNA out of concern for juvenile welfare, Perry probably objected to the federal mandate and to the price. A 2009 study estimated that it would cost Texas $38.8 million to fully implement SORNA. The penalty for non-compliance is the loss of 10 percent of a state’s federal Byrne Justice Assistance Grant. In Texas, that’s about $1.4 million.

When asked for comment on Texas’ policy of listing juvenile sex offenders, a spokesman for the DPS offered only the following: “All 50 states have some form of a sex offender registry, and the Texas sex offender registry is an important public safety tool created by the Texas Legislature designed to provide awareness and specific information to the public as well as law enforcement about sex offenders, their crimes and their locations.”

Nicole Pittman is the Soros Senior Justice Advocacy Fellow at Human Rights Watch and a leading researcher on juvenile sex offenders. Pittman says the DPS spokesman’s generic reply is typical. “Seven years now, testifying in front of Congress and traveling to 34 states, I have never had anyone tell me that it’s a good idea when I’m talking specifically about juvenile sex offender registration,” she says. “The problem, the reason we’re so deep into it, is that [laws] get extended to children and the biggest deal-breaker or career-breaker for a politician is to undo something. They’re so afraid of that. That’s the way you lose votes. And juvenile offenders get caught up in that, even though I have not met a legislator yet who believes that a child should go on there.”

When he left Texas Tech in 2006, Josh was 19. He got a job working at a construction company, but not for long. First, a man on the crew told a story about threatening a sex offender who’d moved into his neighborhood. Josh says the man told the offender, “‘That’s my house over there and those are my kids and if you ever come near my house, I’m gonna blow your brains out.’” Within a month, Josh was called into the manager’s office and let go—for his own safety. “Multiple people had said they planned on throwing me out of the tower,” Josh says.

When he left Texas Tech in 2006, Josh was 19. He got a job working at a construction company, but not for long. First, a man on the crew told a story about threatening a sex offender who’d moved into his neighborhood. Josh says the man told the offender, “‘That’s my house over there and those are my kids and if you ever come near my house, I’m gonna blow your brains out.’” Within a month, Josh was called into the manager’s office and let go—for his own safety. “Multiple people had said they planned on throwing me out of the tower,” Josh says.

He then got a job in the wind industry, traveling around the country putting up turbines. “That went pretty good for about two years, and I did pretty well,” Josh says. “Then I messed up in Washington state.”

Though he was registered in his home county in Texas, Josh was also supposed to have registered in any county where he stayed more than a week, and he’d been in Washington working for over a month. He was arrested and charged with a felony failure to register. He spent 13 days in jail, paid a $2,000 fine, and spent another $6,000 on a lawyer to help him get out with time served. He also lost his job. “When I applied to the company, I didn’t have to put that I was convicted of a felony because I wasn’t,” Josh says. “I was a child and I was adjudicated. My parole officer had said I could leave that blank or put ‘no.’” But that’s not how his employers saw it. “I lost my job and all my work contacts, all the friends I had. And then I had a felony conviction on my record.” Josh’s registration will eventually end, but his criminal record will remain.

Josh moved back to Abilene and worked on a ranch, at a chemical company, and as a mover to make ends meet. Then he met his wife, Nicole, through mutual acquaintances. Josh had never really dated because, after TYC, he was afraid of being considered a predator. “When I was introduced back into church, I felt guilty for looking at girls my own age,” he says. “What father of a 16-year-old girl is going to let their daughter date a 16-year-old sex offender? None.”

Nicole was 22 and Josh was 23 when they went on their first date, to Starbucks. “It was only my second time in a Starbucks,” Nicole says softly. They went for a walk and talked for hours. “When I came home from our first date,” Nicole says, “I couldn’t stop smiling. I thought he was very smart, and he’s very nice and you know…I just fell in love.”

After dating for two weeks, Josh says, “I sat her down. I said, ‘I hope this doesn’t change things. But I know that I need to go ahead and tell you.’ And I told her my story. So I said, ‘If you want to continue this relationship, or if you want to end this relationship, if that scares you, I understand too.’ She kissed me. That was her answer.”

Nicole says, “Being a single mom, you think no one’s ever going to love you. I didn’t let him meet the kids for a while because I didn’t want him to run away. But they fell in love with him. He’s really good with them. That’s a good thing.”

Josh proposed three months later. He had started working at a pizza place in Wichita Falls, almost three hours from Abilene, commuting back and forth to see Nicole and keep his registration in Abilene. They didn’t want to live together before marriage, but the distance was hard, so they got married in October.

Nicole talked to me in her car as we waited for her second oldest to be released from kindergarten. Josh doesn’t pick the kids up or attend any school functions because to do so, he’d have to let the administration know he’s a sex offender and ask for permission. He’s afraid of transferring any stigma to his children.

Nicole says she would have married Josh regardless but admits she didn’t know how much harder life would be because of his registration. “I don’t think it’s right that he has to do this,” she says. “It’s hard for him to get a job. It’s hard for him to stay in one place. I feel like they’re keeping him from living.”

During months of research for this story, I actively tried to find someone to make a case for how the sex offender registry is working and why juveniles should be on it. As researcher Nicole Pittman had predicted, I could not find that person. Even Liles Arnold, Chairman of the Council on Sex Offender Treatment, couldn’t throw his weight behind it. “How well [the registry] works is still something that’s subject to research,” Arnold said. “We don’t have anything definitive that indicates that the sex offender registry has created a decline in sex offending. I think we’re still trying to fine-tune the process.” As for registering juveniles, Arnold says in “very rare cases,” such as a 15- or 16-year-old committing a violent assault with a weapon, “I think you could argue that registration serves a purpose. But for the overwhelming majority of juvenile offenses, I don’t think registration is warranted.”

Multiple studies have shown that juvenile sex offenders have extremely low rates of recidivism. But could being on the registry be why they don’t re-offend?

Again, research says no. Dr. Elizabeth Letourneau is an associate professor of mental health at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and has conducted several studies on recidivism among juvenile sex offenders. Recently, she compared more than 100 pairs of youths who had committed the same sex offense—one person in each pair had been registered and one had not.

Letourneau learned that being on the sex offender registry or having neighbors notified when a juvenile offender moves in had no effect on the likelihood that the youth would commit another violent or sexual offense. She also found that the existence of the registry didn’t prevent first-time offenders. “Juveniles are barely aware of their own behaviors, much less consequences down the line,” Letourneau said.

A month after his wedding to Nicole, Josh bought the pizzeria in Wichita Falls. “It wasn’t making a whole lot of money, but I started to feel like things were changing,” he says. But Josh tried to preserve his new life as a father and businessman by keeping his registration in Abilene. He says, “Being a business owner, especially with a family restaurant, the last thing you want is for people to Google you and see, oh, he’s a sex offender. So I made the stupid decision not to register in Wichita Falls. I maintained my registry with Callahan County, and went back and forth for a while, trying to keep my residence there, but because—and again, I didn’t know this—but any time you spend more than 48 hours in a month in one particular principality, you also have to register with the city of Wichita Falls. Next thing I know I have two detectives coming to my restaurant, asking why I hadn’t registered there. So I picked up another felony in Wichita Falls for failure to register. I lost my restaurant. I had cashed in a 401(k), some gold coins, sold off everything I had saved trying to keep that restaurant. I lost everything.”

It could have been worse. Josh retained a lawyer friend to help with his case, but it didn’t look good. The district attorney wanted to give Josh eight years in prison. They were scared. Nicole was pregnant with their first child.

Through the years, Josh had stayed close to his parents and siblings, including the sister he abused. When she heard Josh might be going to jail, she wrote a letter to the judge.

Dear Sirs and Madams of the Court,

As the only victim of this crime, I feel my brother, Joshua Samuel Gravens, has paid his debt to society and to me for what he did. He was 13 years old at the time and has paid for it for 11 years so far. I have seen my brother work hard, try to pay his bills, take care of his family, get a little bit ahead, only to have the justice system come and take everything away time after time.

For three and a half years he was totally incarcerated and then kept on parole until he was 21. He did well in school and work. Please release him from this penalty and let him go on to live his life. Let him de-register and give him the right to vote. He will be a good citizen. I have full confidence of this.

Sincerely and gratefully yours,

[Redacted]

P.S. I am almost 19 years old.

Josh’s sister declined to be interviewed, and because she’s a victim of a child sex crime, the Observer is withholding her name.

Josh was released with probation and a $2,000 ticket for a child safety zone violation. He is almost finished paying off the ticket.

All 50 states now have a group working to reform sex offender registries. Mary Sue Molnar founded Texas Voices in 2008, after her son was convicted of a sex offense.

“When this happened,” she said, “I started researching. And I found stories that were far more horrendous and heartbreaking than ours. Young kids and young men and dumb mistakes. I thought everybody who was on that registry was a dangerous, violent criminal who was waiting behind a tree to snatch up kids. I never realized.”

Texas Voices distributes email updates to about 500 members and holds occasional meetings in major Texas cities for sex offenders and their loved ones. During the last legislative session, the group successfully lobbied against a bill by state Rep. Tan Parker, a Republican from Flower Mound, that would have printed “RSO” on the back of a registered sex offender’s driver’s license or other state-issued ID. Molnar said it wasn’t useful, just punitive. “Police already know they’re on the registry and they already carry a blue card. So how does that protect the public?”

Texas Voices also works toward public education, using the experiences of its members. “We have a lot of good stories that need to be told,” Molnar said. “When people read them, they understand a little bit more about how easy it is to be placed on the registry and that it could happen to them or someone they love very easily.”

Molnar said she supports the list, but echoes the criticism that it’s too big to be useful. “Hello, not everybody on the list is dangerous,” she said. “We know there are a few out there who are dangerous and who need to be monitored. We don’t have a problem with that. But there are just so many. They are adding an average of 111 [registrants] a week. And hardly anybody gets off. So what do we do now and where do we go from here? What happens when we are at 100,000 and the ones who really need to be monitored, how closely are we going to be able to monitor them?”

The Texas Legislature has taken two small steps back from swelling the registry. Last year, lawmakers passed the so-called “Romeo and Juliet” bill, by Sen. Royce West (D-Dallas), which retroactively de-registered offenders who were older than 17 and had consensual sex with a minor at least 15 years old and no more than four years their junior.

In 2005, the Legislature passed two companion bills creating a process by which certain offenders could petition to be taken off the registry. The Council on Sex Offender Treatment spent years developing an evaluation tool and training a dozen specialists around the state to use it. The idea was for specialists to evaluate sex offenders who were of the lowest tier of offenses and had completed probation without another conviction, then make a recommendation to the offender’s local court, which would have the final say in whether the offender was de-registered. The process officially kicked off July 1, 2011. Since then, they’ve completed between 10 and 15 evaluations. Not one person has come off the list.

State Rep. Jerry Madden, a Republican from Richardson who chairs the House Corrections Committee and is serving his last term in office, says it’s difficult to remove names from the registry—even low-risk juveniles—because no one wants to get it wrong. “There’s not enough knowledge about what that risk assessment is. The thing is, no matter how well you do it, once in a great while, you’re going to miss. … You don’t want to let out the one that’s going to go grab someone’s kid off the street. That’s the danger in all of this.”

While Madden calls the registry an “absolute necessity,” he says some juveniles shouldn’t be listed. “I think we need to know who the sex offenders are but realize also that juvenile brains are still developing. … [M]any of them grow out of it. I think that there needs to be a very careful consideration of who we put on any list as a juvenile.”

Josh and his family moved to Sweetwater in July 2010 to work on a ranch. Nicole loved the country, but the job lasted only a year and a half. “The woman there, the mother was sick and eventually passed away and her son needed to sell the house and move into something else,” Josh says. “And so we came out here to Plano. Moved in with my sister temporarily. The plan is to save some money and move into our own place here in Plano. The nice thing about Plano is, they have residency restrictions but they don’t apply to people who were juveniles at the time of their offense. So I can pretty much move anywhere in Plano without fear of violating the child safety zone, which is nice. And this is the first town there’s ever been any dignity in the registration process. The lady who does the registry here told me everything. Now I know what’s expected of me on the registry.”

Josh briefly had two jobs in Plano, at a Christmas tree lot and, for the same people, doing pest control. But after four consecutive paychecks bounced, he quit. He looks for work in earnest, but he knows from experience that he’ll get hired only by people who can meet him, listen to his story, and decide to give him a chance. “I have to go to mom-and-pop businesses because big corporations won’t hire me,” he says. He recently started food service training to become a waiter. He’s also exploring returning to college part-time to get his bachelor’s.

Nicole Pittman, with Human Rights Watch, met Josh during a recent research trip to Texas. She interviewed him extensively and talked with his family. I asked her how unusual Josh’s story is.

“He is an exceptional person,” she said. “But the only thing that’s exceptional about his case is that they have an error on the record in terms of two victims versus one. But his case is classic, textbook of what I’m seeing. When you look at the letter of the law, you’re like, ‘Okay, I can understand, we want to protect children.’ But Josh, as well as thousands and thousands of others, are also in that protected class. He was a child.”

Pittman is traveling around the country, interviewing juvenile sex offenders and their loved ones to learn about the impact registration has on their mental health. In many cases, she has only the family to interview, because the juvenile has committed suicide.

“I’ve never had thoughts of suicide,” Josh says. “But if any person were weaker than me, mentally or whatnot, it would crush them. I had the benefit of having had a strong support from my family and a strong faith. I still believe humanity is good overall, even though I’ve been through the wringer and I’ve had death threats and society hasn’t been very great to me. I still love my country, and I still love my state. The only thing I want to do is make sure kids don’t go through what I went through. Punish them, if you have to. But don’t put them on the registry.”