Big D’s Culture Game

EDITOR’S NOTE: In the print and earlier Web editions of this story, the Observer mistakenly reported that opera tickets were $40 or more. Three tickets can be purchased for $75.

Hear Michael May’s audio report from Studio360.org:

On a recent Sunday morning, I walked a mile from my downtown Dallas hotel to the new AT&T Performing Arts Center. It was a quiet stroll, bordering on eerie. Huge dark office buildings. Empty sidewalks. I kept a close eye on the directions I’d gotten from the hotel clerk. If I got lost, there wasn’t anyone around to point me on my way.

But as I approached the heart of the arts district, a few signs of life appeared. A couple paused by a fountain. A group of bikers in spandex flew past like a flock of rare birds. The new Margot and Bill Winspear Opera House rose from behind the fountain, with a soaring glass façade and glossy red dome, and across the street stood the new shimmering, metallic Dee and Charles Wyly Theater. By the front door was the person I’d come to meet, Mark Nerenhausen, the president of the AT&T Performing Arts Center. He giddily pointed out the few folks strolling around the plaza. “You know, usually Performing Arts Centers are set apart,” he said. “You walk by them. But to walk through them is pretty cool.”

Dallas has long been seen as a city (and metro area) rich with money but poor on quality of life. Downtown is full of colossal office buildings, huge parking garages and one-way streets that whisk office workers in and back out to the suburbs as efficiently as possible. But Dallas has always strived to be a world-class destination, and its leaders have looked to great architecture and art to make that a reality since 1890, when the city spent $300,000, then an outrageous sum, on a courthouse in the middle of downtown. It showed that Dallas was leaving its Wild West reputation behind.

Dallas has long been seen as a city (and metro area) rich with money but poor on quality of life. Downtown is full of colossal office buildings, huge parking garages and one-way streets that whisk office workers in and back out to the suburbs as efficiently as possible. But Dallas has always strived to be a world-class destination, and its leaders have looked to great architecture and art to make that a reality since 1890, when the city spent $300,000, then an outrageous sum, on a courthouse in the middle of downtown. It showed that Dallas was leaving its Wild West reputation behind.

Nowadays Big D has a collection of modern buildings by famous architects to rival that of any metropolis. Even so, this has been a monumental year for Dallas architecture. Two mammoth projects were recently unveiled that would seem to have little in common: the AT&T Performing Arts Center in the heart of downtown, and a brand-new stadium for the Dallas Cowboys in suburban Arlington. The two have different purposes, to be sure. But with both, Dallas is betting that great art and architecture will create an experience that will further transform its reputation in the 21st century.

The new performing arts center, which includes the Winspear Opera House and the Wyly Theater, completes a plan hatched in 1978, when city leaders drew up an arts district in the northeast corner of downtown, hoping to lure people for something besides a day at the office. The district now houses a symphony hall, several art museums and a public high school dedicated to the arts. “It was a physical plan,” Nerenhausen told me. “But it was also a vision that art and culture could be a defining characteristic of the city, and essential to the future of the city.”

The center updates that vision in important ways. The Winspear Opera House sits next to the Myerson Symphony Hall, which was built in 1989. Both were built using the same method: Raise millions from wealthy Dallas donors, and hire a prize-winning international architect to design the building. But the experience of visiting the two buildings couldn’t be more different. At the 20-year-old symphony hall designed by I.M. Pei, one enters through a parking lot underneath the angular cement-and-glass structure. Audience members never have to go outside. At the new opera house, the escalators from the parking garage empty into the middle of a huge shaded patio in front of the building. People mingle out front before entering the glass-encased lobby.

“We designed the house not to be a more formal old-fashioned opera house where you have to pluck up your courage to come in through a monumental door,” said London-based architect Spencer De Grey who led the project for the Pritzker Prize–winning firm Foster and Partners. “Here the entire lobby is glazed, it’s very visible, and the red drum of the auditorium is a beacon that draws you in. The whole concept is to break down barriers.”

Dallas residents have bought into the concept—literally. The new performing arts center was built with more private funding than any other similar effort in the country, with 133 Dallas families giving more than $1 million each to the $350 million project. But many of these wealthy donors had more in mind than simply a place to go for a night at the opera. The new center’s purpose is as much civic as it is cultural—to create an urban, pedestrian-friendly neighborhood in downtown Dallas. People can use the enormous shaded patio whether or not they’re going to the opera. A new outdoor performance space, now being built, will hold up to 5,000 people for concerts on the lawn. And the city has broken ground on Woodall Rogers Park, a 5-acre stretch of landscaped green space that will stretch over a nearby sunken freeway. The park will help connect the arts district with uptown, a thriving residential neighborhood on the other side of the thoroughfare. “The results we are trying to achieve are so much bigger than us,” Nerenhausen said. “We aren’t trying to control the issue so much as influence the issue.”

Architect Brent Brown lives downtown, and directs the Dallas City Design Studio, which works from inside City Hall to help create public space. He told me that downtown has already come a long way from when he first moved there a decade ago. “Back then, if you wanted to find something to eat for dinner, you might find a slice of pizza,” he said. “It’s still dead on weekends, but that’s changing. There’s a lot more green space downtown now, and it’s giving people a reason to hang around.”

The performing arts center already comes alive around performances. Before a Sunday matinee of Otello, the audience gathered on the Winspear’s patio and began to file inside and up a grand staircase to their seats. Since the entire outer wall is glass, the building comes alive with activity, like a massive ant farm. The opera was sold out, with the older, well-dressed crowd you would expect.

The biggest challenge for the new arts center will be convincing people that it’s not just here for the wealthy few who funded it. The season does include shows by local theaters, and they’ve kept some tickets under $20, but the opera costs several times that, just for the cheap seats. For audience members Norman and Jane Gaddan, Otello was a splurge for Norman’s birthday. “We’re a little bothered by the elitism of it all,” Norman Gaddan said. “This whole arts district, there’s very dramatic unique structures, but it’s very expensive. The venues are small, and I’m sure they’ll keep them full, but most people will not be able to come here.”

When it comes to expensive, the opera is nothing compared to a night at the new Cowboys Stadium. It can cost hundreds of dollars to go to a game. Parking alone begins at $50.

The opera house and Cowboys Stadium opened at the same time, and they’re both masterworks of contemporary architecture that aim to transcend their primary purpose. Comparing the two illustrates how hard it will be for Dallas to change its habits, but at the same time shows how much mainstream support exists here for cutting-edge projects.

The new billion-dollar stadium is far from downtown Dallas. It’s an hour away, in Arlington, a city without a real downtown or a public transportation system. Unlike most new stadiums, which have gone for a retro look, Cowboys Stadium is an aerodynamic glass-and-cement saucer that rises from its sprawling asphalt parking lots like a futuristic cathedral to football. Inside, the décor is more luxury Las Vegas than gritty gridiron. Sleek modern furniture. Soft lighting. Three thousand high-definition TVs. And, in an unprecedented move, 17 enormous contemporary art pieces—sculptures above all the entrances, and huge murals covering hundreds of square feet of concrete above concession stands and in staircases.

The stadium is the vision of Cowboys owner Jerry Jones. But his wife, Gene, insisted on the artwork. She was inspired by what art was doing to downtown Dallas (she’s on the executive board of the Performing Arts Center). “I thought, this stadium just needs to be the same quality, and do the same thing for people who enjoy fine things,” Gene Jones said. “I just wanted this to be the best of the best, and I didn’t think it could be without the art.”

“We knew we were going to have a different type of football stadium,” she continued. “It was going to be very futuristic. And we thought every great building needs art in it. It needed to be contemporary art, to go with the style of the building. And it had to be huge, or you wouldn’t notice it. We wanted to be powerful, explosive, something that reflects a football game.”

Jones brought together an arts panel that included curators from the state’s largest museums. They wanted to commission work that would connect with football fans, but they didn’t shy away from difficult art. One of the artists chosen by Jones and her committee was Houston-based Trenton Doyle Hancock of Houston, known for his colorful, surreal paintings. “My first reaction was, really?” Hancock said. “To have a stadium outfitted with art seemed too good to be true.”

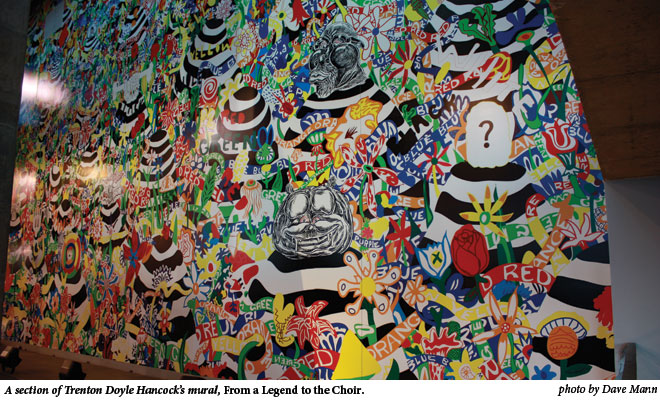

Once he realized the scale of the project, he signed on and started working on a piece called From a Legend to a Choir. His work stretches along a wall on the outer ring of the stadium, and fans can see it from several vantage points as they make their way up a ramp to their seats. The piece is incredibly dense, featuring a flowering field full of Hancock’s distinctive, zebra-striped creatures called mounds, hybrids of a sort between plants and humans. Hancock, who played high school football, worked in some gridiron references. One of the mounds is wearing a football helmet, and they’re lined up on a grassy field, just like the players on the other side of the wall.

The piece is classic Hancock, but the process was different than anything he had gone through before. The arts committee was involved from the conception. “Usually, I go into my studio, and what I make is what you get,” Hancock said. “But this was a bureaucratic process; the final say was not my own. You figure out inventive ways to solve problems, and I’m happy with what we came up with.”

The members told Hancock to avoid any sexual or violent imagery, which sometimes crops up in his work. And his first proposal was sent back—too much pink. “It’s hard to find a football team that uses pink well,” he chuckled. “One thing I heard was that it wasn’t about the pink exactly, but more that it looked red, which was close to the [Washington] Redskins’ color. Whatever the case, the pink was out.”

Walking around inside the stadium as the Cowboys squeaked out a win over the rival Redskins on Nov. 22, it was striking to see football fans framed by cutting-edge contemporary art. Although the game was both fleeting and miles away from Dallas proper, it felt exactly like the kind of public space that arts district officials want to create. All sorts of people mingled with each other, surrounded by great art and architecture, and they were thrilled to be here, together in a common purpose: winning the game.

While the district uses art and culture to transform downtown, the stadium is using art to transform the experience of football. At times, it seems to be working. Fan Rosalind Perry relaxed in one of the stadium’s lounges after the game, near a sculpture of floating stainless-steel orbs called Moving Stars Takes Time by the hot international artist Olafur Eliasson. “It just made me feel like I was floating, like I was high,” Perry said. “I’d already had one margarita, so it just took me to another level.”

But a lot of football fans told me just what you’d expect. I found Travis Smith waiting in line for food, and asked him what he thought of a red-and-white striped mural over the concession stand. It’s by the artist Terry Haggerty and called Two Minds. “Is that art? Looks like a bunch of painting,” Smith said. “I don’t have an opinion about it because I just don’t care.”

When I told Gene Jones that many fans hadn’t noticed the pieces, she just smiled and nodded. “Not everyone knows it’s art, but we’ll teach ’em,” she said in her sweet Dallas drawl. “That’s our goal!”

Jones believes these great buildings and art give the city “credibility.” And there’s no doubt that these bold new buildings have already made a statement that Dallas is willing to bet big on world-class culture. The performing arts center is adding momentum to a downtown that is already changing fast. The football stadium could help turn a young football fan into the next Picasso. Now if the Cowboys could just make it to the Super Bowl again.