A Bloody Injustice

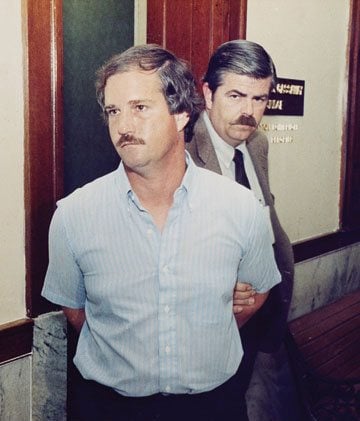

Warren Horinek was a vicious drunk with a history of threatening his wife. But his conviction for murdering her was based on junk science--like thousands of others.

Warren Horinek was so intoxicated he could barely speak. His first words to the 911 dispatcher were mangled and unintelligible. He gathered himself and tried again. The words were still slurred, but he managed to force them out: “My wife just shot herself.”

Horinek had been married to his wife, Bonnie, for three years. Their marriage was turbulent, and some of Bonnie’s friends would later say that Warren—a former Fort Worth police officer whose drinking got him kicked off the force—was abusive. They thought the couple was headed for divorce. But on that Tuesday night, March 14, 1995, they seemed to be having fun. Bonnie had left her office at the law firm of Jackson & Walker in downtown Fort Worth at about 7:15 p.m. and met Warren for dinner at a TGI Friday’s. They hung around the bar and kept drinking, closing their tab at 11:09 p.m. to head home. The Horineks lived about five minutes away, which was fortunate because they were both drunk. Warren had consumed at least 11 Coors Lights. Bonnie had been drinking chardonnay, and tests would later show her blood alcohol level nearly double the legal limit. At 11:39 p.m., a half-hour after they left the bar, Warren called 911.

On the recording, he is frantic. As the dispatcher contacts paramedics, Warren can be heard in the background yelling, “Why’d you do that, goddammit. Why? Why? Why? Why?” When he returns to the phone, he is panicking. “Are you there? My wife just shot herself. Get over here now!” The dispatcher tries to calm him, saying an ambulance is on the way. “She’s already blue,” Warren says. The dispatcher tells him to begin CPR. In the background, Warren can be heard breathing into Bonnie’s mouth. He picks up the phone again: “I need somebody here.” Is she breathing? the dispatcher asks. “She shot herself in the throat, I think.” Is she breathing? “Yes, she’s breathing,” Warren says. After a pause, he adds, “Goddamn, get somebody here now!”

By the time paramedics and police arrived, Bonnie Horinek had died. She was lying on the bed in her pink nightgown with a single gunshot to the chest. Warren was still performing CPR. Paramedics told him it was too late, but he wouldn’t stop. When they pulled him off the bed, he scrambled back to her body to continue chest compressions. The paramedics eventually had to drag him from the room.

When police examined the scene, they found two weapons on the bed: a bloody .38-caliber revolver next to Bonnie and, on the edge of the bed, a 12-gauge Winchester shotgun. There was no sign of a break-in. No one else was in the house. There were two possible scenarios: Either Bonnie Horinek had committed suicide, or her husband, in a drunken rage, had killed her.

From the start, Warren Horinek has claimed his wife shot herself. As the police investigation unfolded, the people normally responsible for sending a murderer to prison—the crime scene investigator, the police sergeant who oversaw the homicide investigation, the medical examiner who performed the autopsy, even the assistant district attorney initially assigned to prosecute the case—all came to believe that Horinek was telling the truth.

When Horinek was tried for murder, they testified in his defense. Their testimony and expertise wouldn’t matter. Horinek’s fate would hinge on a few specks of blood found at the scene. A few specks of blood, that is, along with the testimony of a single forensic expert who may have misread the evidence. As a result, an innocent man may spend decades in prison. He won’t be alone.

Initially the crime scene puzzled Fort Worth police. Why were there two guns on the bed with Bonnie Horinek’s body? Why was a pillowcase wrapped tightly around her neck? Why was there so much blood on Warren’s T-shirt? Where was the bullet?

One of the first officers on the scene, J.D. Roberts, theorized that Warren had shot Bonnie with the shotgun and tried to strangle her with the pillowcase. That theory was debunked by the autopsy. The medical examiner’s office determined that Bonnie had been shot with the .38. The bullet had ripped a path through the mattress, box spring, and carpet, and left a mark in the house’s foundation, though the bullet was never found. The autopsy also showed she hadn’t been strangled. The pillowcase, which Warren said he wrapped around her neck because he thought she’d shot herself in the throat, had caused no damage.

Besides the single gunshot wound, Bonnie had no other injuries. There were no signs of a struggle. The wound to her chest, the autopsy showed, was a contact wound, meaning the gun had been placed firmly against her skin. While the manner of death was officially classified as “undetermined,” the autopsy report made clear that the medical examiner’s office believed Bonnie had likely committed suicide. “Both the location and proximity of the gunshot wound along with absence of defensive wounds are suggestive of a self–inflicted gunshot wound,” the report reads.

The case landed on the desk of Mike Parrish, then an assistant DA in Fort Worth. After reading the autopsy report and speaking with police officers and the medical examiner, Parrish decided not to prosecute Warren Horinek for murder. “I always thought that it was suicide,” Parrish says. “Still do.”

But Bonnie’s parents, Bob and Barbara Arnett, found the notion that their daughter had killed herself ridiculous. She had too much to live for. Here was a successful attorney with a budding career. She had just landed a posh new job at a major downtown firm, where she was earning a six-figure salary practicing labor law. True, Bonnie had experienced periods of deep depression, particularly after her first marriage had ended. But the half-dozen friends and co-workers who later testified at trial said Bonnie seemed mostly happy. She fretted about her crumbling marriage and what people would think if she were twice-divorced, they testified. None thought she was contemplating suicide. She just seemed too upbeat, they said. To Bob and Barbara Arnett, it was obvious: Their daughter had been murdered by their son-in-law.

He was a drunk—and an obnoxious, occasionally violent, drunk. Bob Arnett, who was an engineer for Lockheed Martin Corp. in Fort Worth, never understood what his daughter saw in Warren Horinek, he told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in 1996. He thought she could do better. He would often meet Bonnie for lunch in downtown Fort Worth, but he told the newspaper that she never told him how bad the marriage had become. She did confide to friends that when Warren was drunk, which was often, she was afraid of him.

When the district attorney’s office refused to prosecute, the Arnetts couldn’t believe it. So they decided to do it themselves. Bonnie’s parents hired an attorney and a private investigator, who unearthed several incidents that would make for compelling, though circumstantial, evidence against Warren Horinek.

For one thing, when he was drunk, Horinek liked to play with guns. He had served on the Fort Worth Police Department for nearly nine years, beginning in 1985, and he kept a healthy collection of firearms in the house. One night in 1992, when he and Bonnie were living together in the Fort Worth suburb of Benbrook before they married, police had been called to the house after neighbors heard gunshots. It turned out that Horinek had gotten drunk and was firing into the pool.

The following year, after another night of drinking, Horinek fired a gun over Bonnie’s head while she lay in bed. The bullet entered the wall a foot-and-a-half above her pillow. Explanations for this event vary. At trial, the prosecution contended Horinek did it to frighten his wife—part of a pattern of abuse. Horinek, interviewed recently by the Observer, calls the incident “inexcusable.” He says Bonnie had been playfully ignoring him, hiding her head under her pillow. “I’m not listening to you,” he says his wife was saying. “Stupidly,” he says—as a joke and to startle her—he fired the gun into the wall. He contends that he didn’t shoot at Bonnie, that the nose of the gun was pressed against the wall and tilted upward when he fired it. (A private forensic expert hired for the defense, Max Courtney, testified that he found evidence to verify Horinek’s claim. Courtney said he found gunpowder traces on the wall, which would have happened only if Horinek had pressed the weapon against the wall when he pulled the trigger.)

That wasn’t the end of Horinek’s suspicious behavior. Later in 1993, his drinking cost him his job with the police. The day he was forced to resign, he got drunk, shut himself in a room and threatened suicide, according to court testimony. Bonnie called the police. Officers arrived and calmed Horinek down. Police regulations required that he be taken for a psych evaluation at the emergency room. As Horinek was led away, several officers would testify at trial, he shouted to Bonnie that he would make her pay for doing this to him.

With these snapshots of Horinek in hand, the Arnetts and their attorney, Mike Ware, decided to circumvent the district attorney’s office. Ware knew about a rarely used quirk in Texas law that allows any concerned person to bring evidence before a grand jury. While there was little physical evidence of murder, the grand jury found Ware’s presentation convincing. In March 1996, a year after Bonnie’s death, Horinek was indicted for murder.

The Tarrant County district attorney’s office refused to act on the indictment. It’s not often that a Texas prosecutor refuses to go after an indicted defendant. But Assistant DA Parrish wouldn’t do it. “Ethically, if you don’t believe they’re guilty, then you can’t prosecute,” he says. With the DA’s office recusing itself from the case, the judge assigned two attorneys in private practice to serve as special prosecutors.

That led to an upside-down trial in which nearly everyone trying to convict Horinek was in private practice—private attorneys serving as prosecutors, using private forensic experts and private psychologists. Meanwhile, the agents of the state—the district attorney, crime scene investigator, and homicide sergeant—were all siding with the defendant. In 27 years at the Tarrant County DA’s office, Parrish had never seen such a bizarre case—and never did again. Nobody had.

From the start, Horinek says his lawyer assured him there was nothing to worry about. He figured it wouldn’t even reach a grand jury. “Even the DA believes you’re innocent,” his attorney said. After Horinek was indicted anyway, his lawyer predicted the case would never come to trial; the county didn’t want to prosecute him.

Once he went to trial, Horinek was again reassured: He could never be convicted. There was no evidence. As bad as the private prosecutors would make Horinek sound, as compelling as the anecdotes of drunken gunplay were, that was all circumstantial evidence—incidents that occurred months or years before Bonnie’s death. You can’t be convicted of murder for being an obnoxious drunk or an abusive husband.

For most of his trial, Horinek’s attorney seemed prescient. The jury appeared to be convinced of his innocence. Later, when this anything-but-textbook trial was over, the foreman would say that the jurors were going to acquit Horinek. That was before the prosecution’s final witness took the stand. This case, like hundreds of others, was decided by the testimony of a single forensic expert.

His name is Tom Bevel. He’s a private, Oklahoma-based expert in bloodstain patterns. The study of blood spatter has been around since the 1890s. But unlike other forensic evidence—DNA or fingerprinting, for example—blood spatter evidence rarely provides the sole basis for prosecution. Blood patterns—like those found on Warren Horinek’s Hard Rock Cafe T-shirt that night in 1995—can be used to augment evidence in a criminal case, but they’re rarely the only evidence. The reason is simple: Bloodstains can tell you only so much about who committed a crime, or how. Some experts, Bevel included, have tried to use blood-spatter forensics to reconstruct where blood came from and by what method. If that sounds fantastical, it sometimes is.

In recent years, flawed blood-spatter evidence has led to at least three wrongful convictions across the country, from North Carolina to Indiana. In 2009, the National Academy of Sciences released findings from the most extensive study ever conducted of forensic evidence in American courtrooms. The authors didn’t think much of blood-spatter analysis, writing that the “uncertainties associated with bloodstain pattern analysis are enormous,” and concluding that the opinions of blood-spatter experts like Bevel are “more subjective than scientific.”

In that respect, bloodstain analysis is similar to other kinds of forensic science. With the exception of DNA testing, much of the forensic evidence used in U.S. courts—including fingerprint matches, ballistics, and arson evidence—is based on junk science. CSI it ain’t. Contrary to what’s portrayed on television, bullets are regularly matched to the wrong gun, fingerprints are misidentified, crime labs botch their analysis, and accidental fires are misread as arson.

Most criminal-justice experts believe that flawed forensic evidence—and overreaching expert witnesses—have sent thousands of Americans to prison for crimes they didn’t commit. The solution is to ensure that forensic testimony is based on sound science. Reconstructing how blood flies through the air is obviously dicey business. The science academy recommends that anyone attempting to analyze blood patterns have an advanced degree (or expert knowledge) of applied mathematics, physics, and the pathology of wounds.

Bevel, whose testimony sent Warren Horinek to prison, has no such advanced degrees, Though he has taken professional courses in these subjects, he has little background in science. He spent nearly three decades in the Oklahoma City Police Department and developed an interest in blood spatter. He began contracting out his services as a blood-spatter expert, usually testifying for the prosecution. Eventually, he taught courses and has published three editions of a textbook, Bloodstain Pattern Analysis with an Introduction to Crime Scene Reconstruction.

Horinek’s 1996 trial took place 13 years before the academy’s scathing report on the limits of blood-spatter analysis. So when Bevel took the stand as a rebuttal witness—one of the last people the jurors heard from—they found him awfully believable. The defense had neither the academy study, nor other known cases of wrongful conviction, to poke holes in Bevel’s impressive-sounding expertise.

Bevel had studied the T-shirt Horinek was wearing the night Bonnie died. It was covered in blood. Bevel was especially interested in the dozens of small specks of blood on the shirt’s left shoulder. Were these spots caused by Horinek’s administering CPR or, perhaps, by a gunshot?

The tiny size of the blood spots was the key to their origin, Bevel said. Spots so small had to originate from a “high velocity occurrence”—a gunshot—rather than from CPR. “If the … majority of the bloodstains are well below one millimeter in diameter and less, then that is consistent with what you’d expect to find from a high velocity occurrence. … There are better than 100 bloodstains that you can find with the stereoscopic microscope specifically to the left side of the shirt that are certainly consistent with a high-velocity occurrence,” Bevel testified. He said this indicated, with little doubt, that Horinek had shot someone at close range.

The defense never countered Bevel’s testimony. At a later appeals hearing, the foreman, Bruce Peters, was asked what convinced the jury that Horinek had shot his wife. “The gentleman who testified last, to the atomized blood, was the one that, in my opinion, put him in the scene of the crime,” Peters said. Horinek

as convicted of murder and sentenced to 30 years in prison.

At the time, hardly anyone suspected the conviction was based on flawed evidence. After Horinek went to prison, the case faded into history. The jury members went back to their lives, the criminal justice machine moved on, and most everyone forgot about the former police officer sitting in prison. All except one person.

“This case has haunted me since 1995,” says Jim Varnon. “There are dozens of reasons that all indicate this was a suicide.” He always believed Warren Horinek was innocent. And for the past 13 years—ever since Horinek wrote him a letter asking for help—he’s been trying to overturn the conviction.

Varnon is no innocence attorney. He recently retired after 35 years in the Fort Worth Police Department, the last 25 as a crime scene investigator. He was one of the first officers at the scene the night Bonnie died. When he arrived, he vaguely recognized Horinek’s face from Warren’s years on the police force, but the two men didn’t know each other before that night. The evidence convinced Varnon that Horinek was innocent.

Varnon has a presentation he gives about the evidence in the case: a half-dozen large boards adorned with crime scene photos, trial testimony, blood-spatter recreations, and his own field notes. It’s become famous in the Fort Worth Police Department.

Varnon contends that the physical evidence verifies Horinek’s version of events. Horinek has supplied the same consistent story since the night Bonnie died (including in a recent prison interview with the Observer): He and Bonnie returned home from TGI Friday’s and got ready for bed. Warren went to his study to check messages (he had a home business that provided companies with language translators). He heard a single gunshot. He assumed someone had broken into the house, so he grabbed a shotgun and rushed to the bedroom, where he found Bonnie bleeding from an apparent neck wound. Blood had pooled at her neck, which, combined with her strained breathing, made Warren mistakenly think she had been shot in the neck, not the chest. He wrapped a pillowcase around her throat and called 9-1-1.

The pillowcase is an interesting piece of evidence. Why would Horinek wrap it around her neck, Varnon wonders, if he wasn’t telling the truth? If he’d shot her, he’d know where the wound was. What’s the point of wrapping something around her neck? It might backfire and make police think she had been strangled, which some officers first believed.

Then there are the two guns. The autopsy confirmed that Bonnie had been shot with the revolver. So, Varnon wonders, why was the shotgun in the room if Horinek isn’t telling the truth? If he staged the scene to look like a suicide, why bring the shotgun in and risk the presence of another weapon incriminating himself?

And the scene looked like a suicide. As police reported, there were no signs of a struggle, and as the medical examiner found, Bonnie’s body had no defensive wounds or other injuries. “I’ve worked hundreds of suicides involving a gunshot,” Varnon says. “When they occur on a bed, a person is frequently lying just like she is. The gun is within reach normally. So often they go where it’s comfortable, which is their bed.”

Varnon has also seen hundreds of contact gunshot wounds, and he remembers only one that wasn’t a suicide. The reason is twofold: If you pull a gun on someone, getting close enough for a contact wound invites a struggle. And if two people are already struggling for a gun, it’s rare that the killer can overpower the victim enough to inflict a contact wound. In the crime scene community, Varnon says, a contact wound is almost always a suicide. “If that was a murder, he’s smarter than all of us in crime scene and all of us in homicide all put together, because he left no evidence of it,” Varnon says.

Of course, Horinek is a former police officer. If he knew these tendencies among investigators, might he have staged the scene as a suicide?

There are two factors, Varnon points out, that make a staged scene unlikely. First, Horinek didn’t have time. The 911 call establishes a short time frame. Bonnie died within minutes of being shot, and she was clearly still alive when Horinek dialed 911 (her labored breathing is audible on the recording). The 911 tape ends when the paramedics arrive. So if Horinek staged the scene, there was a window of only a minute or so before he called 911. There is one other reason Varnon and others believe Horinek couldn’t have staged a suicide like a master criminal: He was fall-down drunk.

“If you hear the 911 tape, you can hear Horinek is shit-faced,” says Parrish, the former assistant DA. (At one point in the call, after performing the first round of CPR, Horinek can be heard pressing buttons on the phone in an apparent attempt to dial 911 again, though the emergency dispatcher was already on the line.) Moreover, Parrish says Horinek’s tone on the 911 tape is compelling evidence. About a minute into the call, Parrish says, “You can hear the adrenaline kick in.” Horinek’s tone does change. His sentences sharpen, and his voice is panicky, desperate, insistent that he needs help. It sounds like he just walked in on a suicide.

Still, these are the same arguments that Varnon and Parrish and homicide Sgt. Paul Kratz made during Horinek’s trial—and they didn’t work. If Varnon was going to make headway on overturning the murder conviction, he had to confront Bevel’s blood-spatter testimony. He had always doubted Bevel’s analysis. It’s well known in the crime-scene community, he says, that CPR (or even a bloody nose) can leave flecks of blood on a shirt—which Bevel testified was not possible. “There are many things that can cause that fine mist of blood, not just a gunshot wound,” Varnon says.

Varnon took his poster boards to upstate New York and presented the case to Herb MacDonell, a renowned forensic scientist whose groundbreaking research on blood patterns in the early 1970s made the field more scientific. He is often called the father of modern bloodstain analysis. (Bevel himself studied for a time under MacDonell.) MacDonell found his former student’s testimony suspect. In 2005, he asked a prominent analyst who’d worked in his lab, Anita Zannin, to examine the case. After studying all the documents and evidence, she concluded—and MacDonell later concurred after his own analysis—that Bevel’s initial testimony was utterly incorrect.

Zannin and MacDonell contend—in a report and two affidavits—that blood spots smaller than one millimeter aren’t necessarily the result of a gunshot, as Bevel testified. Flecks that small can often result from CPR or someone with a punctured lung trying to breathe.

To prove it, MacDonell set up an experiment at his lab in Corning, N.Y., in which a student placed a small amount of blood in his mouth and then simply breathed on a white shirt. The result was a blood-spatter pattern similar to the one found on Warren Horinek’s shirt.

There is no way to reliably determine if the spots on Horinek’s shirt were the result of a gunshot or of CPR. For that reason, Zannin and MacDonell say, blood spatter never should have been used as key evidence against Horinek.

Bevel has defended his work in the case. But in a recent interview with the Observer, Bevel backed away from his testimony that the size of the blood spots is what matters. Bevel now has two different reasons why he believes Horinek is guilty. The first is the appearance of the blood spatter. Blood that a person breathes out has a lighter color and a more bubble-like appearance because it contains more air, Bevel contends. Because the blood on Horinek’s shirt is a normal color, it’s likely the spatter resulted from a gunshot wound, not CPR. But these bubbles aren’t always present. So Bevel also concedes that the lack of bubbles on the shirt doesn’t necessarily eliminate CPR as a cause. He now agrees with Zannin and MacDonell that blood spatter from CPR can sometimes look very much like spatter from a gunshot wound.

That leads him to the second reason he believes Bonnie Horinek was murdered: the lack of a blood spatter trail. If the specks on Warren’s shirt had come from blood that Bonnie breathed out of her nose and mouth, then there would be a trail of spatter leading back from the shirt toward her face. “You have to look at the context of this scene,” Bevel says. If the spatter came from CPR, then “you should be able to find more of that type of spatter between where the shirt reportedly was and the mouth and the nose.” He doesn’t remember finding any.

The problem with that reasoning is that Bonnie’s chest, neck and face were soaked with blood, which could easily have obscured any small spatter she breathed out. And Bevel concedes he can’t be 100 percent sure what happened that night. “There has to be a foundation with which you’re able to call it,” he says. “In this particular case, in my opinion, the best explanation is that it is from a gunshot. In science, there is no 100 percent. It just doesn’t exist. You look at the data, the possibilities, what is found, what isn’t found, and you try to identify the best explanation.”

That isn’t enough to base a murder conviction on, Zannin and MacDonell say. Though they can’t be sure, Zannin and MacDonell suspect that the blood spots were the result of CPR. For one, a single gunshot is unlikely to produce the amount of spatter seen on Horinek’s shirt. Secondly, if Horinek had been leaning over Bonnie while delivering mouth-to-mouth resuscitation—as the 911 recording and police testimony indicate—the left shoulder of his shirt would have been perfectly aligned with the gunshot wound in her chest. That’s where the blood spatter appeared. Also, the bullet punctured her lung, which makes it likely that Bonnie would have breathed flecks of blood on anyone giving her CPR.

These experts’ conclusions add up to a chilling irony: In effect, Horinek’s attempts to revive Bonnie resulted in blood spots that—in the hands of the wrong expert—led to his conviction.

After working on the Horinek case for more than three years, bloodstain expert Zannin contacted Waco attorney Walter Reaves, who handles innocence claims pro bono. Reaves became convinced that Horinek had been railroaded. He gathered affidavits from Varnon, Mike Parrish, Zannin, and MacDonell. In May, he began the legal process to get Warren out of prison by filing a writ of habeas corpus.

These post-conviction writs are always a long shot, especially in cases without testable DNA that can conclusively prove innocence. Horinek remains hopeful, though. “I think this is going to work,” he says. After already serving 15 years, Horinek also will come up for parole for the first time next year.

In the meantime, he waits in prison, one day blending into the next. It could be worse. The flaws in forensic evidence have likely sent many other innocent people to prison, and unlike Horinek, most of them don’t have former district attorneys and police officers working to free them.

Instead, many wrongful convictions—whether due to faulty blood-spatter analysis, misread fingerprint matches, shoddy lab analysis, or junk arson science—disappear into the shuffle of the criminal justice system. No one knows about them. And there’s little chance they’ll ever be overturned.

Listen to the 9-1-1 call (WARNING: includes graphic material)

Listen to Dave Mann discuss this article for the Texas Observer podcast series.