Review

New Orleans Agonistes

Hurricane Katrina was the costliest hurricane in U.S. history. Most of us still have in our heads images of the flooding of New Orleans and its neighboring parishes, and the suffering of people stranded in their devastated city. We also have opinions about the failure of local, state and national government agencies to prevent and respond to the disaster.

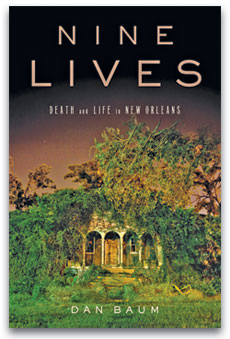

In Nine Lives, Dan Baum tries to help us understand what the disaster meant for the people of New Orleans, how they feel about the slow rebuilding of their city, how they deal with political corruption and incompetence, and what they lost in economic, cultural and human terms. “[T]he nine intertwined life stories” in his book, Baum explains, are his “attempt to convey what is unique and worth saving in New Orleans.”

Baum’s nine principal informants, as he describes them, include “a retired streetcar-track repairman from the Lower Ninth Ward, a transsexual bar owner from St. Claude Avenue and the jazz-playing parish coroner, a white cop from Lakeview and a black jailbird from the Goose.” Their stories give us a feel for their neighborhoods as communities with diverse ethnic and racial compositions, distinctive local cultures and value systems, and different degrees of importance to the local, state and federal governments.

Nine Lives is not a standard oral history. Baum did interview his informants, and they “unpack[ed] their innermost moments for a stranger. … They invited me into their heads and hearts, so that seemed to be the best place from which to tell their stories.” But of Baum’s nine informants, only the “black jailbird,” Anthony Wells, an off-and-on addict, has his story told in direct quotations.

The other eight are told in the manner of historical fiction. Baum explains: “I have re-created scenes and dialogue based upon what my sources told me. I put words to thoughts and feelings that, during the months working on this, were laid bare by these remarkably candid people.” Baum admits that he changed the names of “three peripheral characters to avoid hurt feelings,” but he assures us that “nothing here is invented out of whole cloth.” Note that Baum speaks of real people here as “characters.”

The result does for New Orleans what John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil did for Savannah. It gives us a good sense of what made New Orleans special well before Katrina hit and why its people have responded as they have to death and destruction, and to the much-delayed help in rescuing them and in rebuilding their city. Baum’s narrative begins with older informants shortly after Hurricane Betsy sent floodwaters into the city in September 1965. The stories continue up to 2007, two years after Katrina.

We get to know these individuals and the city they still call home. We get to understand what they mean when they tell Baum that New Orleans wasn’t and isn’t “the worst-organized city in the United States,” but “the best-organized city in the Caribbean.” We get a feel for life among the poorest residents of the neglected Ninth Ward and its large, almost rural, “jungly lots.” We come to understand the peculiar outlooks of New Orleans’ social and political elite, both established families and arrivistes like Billy Grace, Baum’s “millionaire king of carnival” who lives at 2525 St. Charles Avenue, one of the most important addresses in the New Orleanian social register. Every year during Mardi Gras, this stately old house hosts a formal toast to the carnival Rex of 1907. Continuing this tradition was almost as important in reviving New Orleans’ public spirit as rebuilding the city’s infrastructure.

Through Baum’s stories, we also get a feel for New Orleans’ native myths, and its attitudes toward skin color, wealth, class, gender, sexual identity, religion, education, opportunity and power. This is a big list, but Nine Lives delivers insights into each.

One myth, especially, now finds itself challenged, if not shattered, for many residents, black and white, rich and poor. Before Katrina, according to Baum’s informants, citizens would mix at times across social, political and economic barriers and color lines with little wariness and without outright antagonism or deep misunderstanding. Many New Orleanians wanted to believe that in their city, differences of wealth, power, status and color never outweighed respect for basic human dignity. After Katrina, none of Baum’s informants believes that.

While Baum’s intertwined stories read like good fiction, they convey the same sense of reality as the late Studs Terkel’s oral histories about race, the Great Depression, and the working lives of Americans. Eventually we come to understand the effects of Katrina with our own hearts, and we grasp the deep sorrow, disillusionment, and near-ruin the hurricane and the inept response by gov-ernment agencies and officials brought to the lives of so many residents.

If you want to know what it felt like to be poor, abandoned, and forcibly evacuated from New Orleans, just listen to Anthony Wells:

Finally they put us on a plane, a regular airline plane because they’d run out of Army planes. The whole time they wouldn’t tell us where we were going. “You’ll know when you get there,” they said, but what kind of shit is that? … Like we was under communism or some shit. … Set down right before dawn. When we come to a stop, the door opens and this white man gets on. He’s wearing a suit and tie all buttoned up, and it’s five o’clock in the morning. He looks like a preacher. I look back to see what he’s looking at, and oh Lordy Jesus, that plane was full of stinking, crazy-looking niggers. We got dogs, we got cats. We got that dude with the motherfucking hedgehog. … This little white dude in the suit, he must have thought his world about ended. The best of New Orleans delivered up fresh to his doorstep! But I’ll tell you, he was cool. He smiled like he was on a game show. Said, “I am the mayor of Knoxville, Tennessee, and I’m here to welcome you to my city.”

Wells finds out the hard way one reason Knoxville eagerly takes in Katrina refugees. From his perspective, the city and its businesses profited off the misery of the refugees, who were given no information or choice about where they were going, how and how long they would be temporarily housed, or what practical forms of assistance might be available in Knoxville to help them rebuild their lives. There wasn’t even local bus service close to their temporary housing.

Wells saw virtually none of the assistance money he was promised, and he is charged handsomely for rent in the apartment complex where the refugees were forcibly placed. Wells experiences what he considers overt racism of a kind he never felt in New Orleans: “The white people [in Tennessee] think everything is theirs. Only reason we’re not sitting at the back of the bus is because they ain’t got no buses.”

In New Orleans, meanwhile, the poor congregants of St. Augustine Church, are “consumed in losing struggles-against FEMA, insurance companies, the state rebuilding authority, the federal housing program, crooked contractors who had descended on the city like vultures.” Another of Baum’s nine main informants, Frank Minyard, the longtime parish coroner and one of the book’s real heroes, discovers the reason for delay after delay in collecting bodies for autopsy and identification. Minyard, as coroner, was there waiting for bodies to be brought in. Leaders of the 82nd Airborne and National Guard volunteered to have their troops collect the bodies. But they were forbidden to do so, in Minyard’s opinion, while the Bush administration contracted with a private company to do this critical job.

In Minyard’s view, private profits trumped identifying bodies for the sake of grieving families, relatives and friends, and acting quickly to head off the public health crisis of decaying corpses in the streets. Minyard says flatly, “Let me see if I’ve got this straight. Dead people rot on the streets of New Orleans for a week and a half so the feds can sign a private contract.” He later realizes that corpses are being listed as dying of “natural causes” so FEMA and private life-insurance companies can avoid paying out on hurricane victims. “I’m putting all these down as storm-related,” he decides. “These are my people. It’s the least I can do.”

Another low-key New Orleans hero, before and after the storm, is high school band instructor Wilbert Rawlins Jr. His narrative begins in 1980, when he is 10 years old, and continues through a post-Katrina rebuilding event. There, one of the many boys Rawlins influenced with structure and discipline and his presence as a father-figure says, “I got one brother dead and another at Angola, and if it wasn’t for Mr. Rawlins, I might be right there, too.”

Rawlins’ dedication represents the spirit of many average New Orleanians, those who continue to care enough about their city, and about each other, to endure, rebuilding homes and lives together.

Tom Palaima is Dickson Centennial Professor of Classics at the University of Texas at Austin, where he teaches seminars on the human response to war and violence.