Review

One Day in Dallas

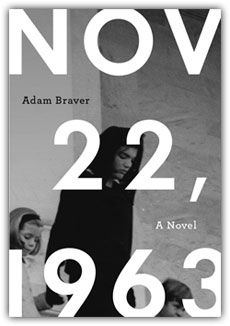

Adam Braver’s novel about that day in Dallas, published in November 2008, 45 years after the assassination, apparently arrived too late for Texas media to take note. Near the end of December, I discovered the book serendipitously at my local Barnes & Noble, and so far as I know the only newspaper in the state to review it was the Houston Chronicle, which ran a canned review from the Los Angeles Times.

Braver’s book deserves to be known in these parts; it ranks first, I believe, among novels focused on the death of JFK. These include Edwin Shrake’s Strange Peaches (1972), Bryan Woolley’s November 22 (1981), and Don DeLillo’s Libra (1991). Shrake’s roman à clef approach draws heavily on his firsthand experiences with friend and fellow writer Gary Cartwright in the hard-partying world of the Dallas rich in the months leading up to the assassination. Woolley presents a multiple third-person point of view, in the manner of John Dos Passos, to create a montage of fictional characters and their actions on November 22. DeLillo arrived on the scene with conspiracy guns blazing through one of his typically paranoid plots, which is nearly impossible to follow or summarize. All the while, he spiraled out enough dazzling prose to keep readers involved, if somewhat confused.

Arguably the only work that eclipses these interpretive responses is The Warren Commission Report (1964), authored by the President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, which, I am now convinced, largely got it right.

Perhaps Braver was drawn to the story because it occurred in the year of his birth: 1963. In any event, his novel stays away from conspiracy theorizing and obfuscation, instead focusing on the most intimate of physical and psychological details. He employs clever subheadings to mark narrative sequences-“Walking Spanish” (you have to read the novel to find out what this means), “It’s Mandatory,” “Seven Reasons Why She Knows She’ll Never Go Back to the White House,” and so forth.

The she in the quotation above, obviously, is Jackie Kennedy, and if the novel belongs to a single character, it belongs to her.

November 22, 1963

Braver’s Jackie is a woman deeply in love with her husband, though she is aware of the scents of other women on his person. The trip to Dallas, one might not recall, was Jackie’s first public appearance following the death of the couple’s infant son Patrick a few months before. The reader, thinking about the purpose of their visit to this distant province, realizes that it was Lyndon Johnson’s failure, his petulance, his pique, his inability or unwillingness to heal the breach between Gov. John Connally and Sen. Ralph Yarborough, that impelled Kennedy to make the journey in the first place. Team Kennedy did not want to go to Texas, but JFK felt he had to. This is but one of the many what-ifs dogging our memory of that day.

Another, unremarked in this novel, is that if Lee Harvey Oswald had secured a requested visa to travel to Cuba, he wouldn’t have been in Dallas when the president was. Instead, Oswald would have been entering his latest fantasy world, Communist Kumbaya City, Castro’s Cuba.

(In an apparent error of fact on Braver’s part, he refers to “… a hammer … being cocked on the sixth floor.” The phrase doesn’t seem quite right to describe the workings of a bolt-action rifle.)

But the novel is not about Oswald, an oblique, unseen, unknown figure whose presence marks the novel in only the most tangential way. November 22, 1963 is about Jackie and the emotional and psychological impact of a shooting that shattered a woman’s world and traumatized a nation.

Braver inventively seizes on both fictional and factual strategies to breathe new life into that day of death. Here, for example, is how he describes Mrs. Kennedy waiting for the new president to be sworn in on Air Force One-an act she can scarcely bring herself to consider:

Sophisticated.

Charming.

Graceful.

Demure.

She used to be known by adjectives. Now she is just an object. There are no modifiers to describe her.

Braver also opens his own lines of investigation into the event, examining facts that seemingly no one has examined before. Consider Kennedy’s salary. He was taken off the federal payroll at 2 p.m. Eastern Standard Time, November 22, 1963. Who says the federal government can’t act with dispatch? At that same moment, Johnson’s pay nearly tripled.

Or consider the casket. There’s a whole chapter devoted to the casket. We learn of its original purchase by a funeral home in Dallas and of its waiting in storage for nine months until it was ordered brought to Parkland Hospital to house the dead president’s body. It was a high-end casket, priced at $1,031.

A Dallas funeral director haggled for two years with the Kennedys and the government over payment for the casket and “professional services.” The government wanted an itemized bill, and the funeral director, finally tiring of the delay, traveled to Washington to collect the casket. The government wouldn’t allow that. (Backtracking: As soon as the president’s body arrived in D.C., another, more modest, casket was purchased from a local funeral home). At the request of Robert Kennedy, the Dallas casket was weighted and dropped into the Atlantic in February 1966. He couldn’t stand the idea of its surviving as an artifact of his brother’s death, on display in Dallas or somewhere, like Bonnie and Clyde’s death car.

The novel is filled with such material history. A harrowing chapter is devoted to the autopsy and the Zapruder film receives an enriched new context. Obscure actual figures like Dallas motorcycle policeman Bobbie Hargis, who was so close to the presidential limousine when the fatal third shot rang out that he was splattered with brain matter, are brought front and center to tell their stories again.

The only time Braver’s inventive technique falters is the chapter titled “Mrs. Kennedy Is Coming Back,” which is narrated by an African-American member of the White House staff. Here Braver’s accustomed sharpness of language gives way to a kind of hushed, reverential tone that seems stilted and forced. There is one telling point to be made by the interruption: One of the staff has been in the presence of the new president and, pressed as to what differences other staff members can expect, he tells his colleagues that Johnson is “louder.” That one word speaks volumes.

“Louder” doesn’t get quite all of Johnson. “Jackass” perhaps comes closer. Braver reports three telephone conversations between the new president and the dead president’s widow. I had read these exchanges before, but their appalling nature acquires new force in the rich ambience of the novel’s emotional turmoil. In a phone call on Dec. 2, Johnson called Jackie “sweetie” and flirtatiously invited her to come to the White House to see him. In a call on Dec. 7, the president said Jackie looked “gorgeous” in a recent photograph and again implored her to visit the White House so he could take a walk “down to the seesaw with you like old times.” The last thing he said was to hug her children and “tell them I’d like to be their daddy.”

Braver’s novel shows what can be done when a writer delves deeply into the textures and facts of a historical event about which we thought we knew everything. Of course we did not; we never know everything. His curiosity and reconstruction brings to life the human drama in a way that Oliver Stone and a roomful of conspiracy buffs never could. Yet the conspiracy buffs get all the press. Braver’s novel deserves a bigger share.

Don Graham’s most recent book is State Fare: An Irreverent Guide to Texas Movies (TCU Press, 2008).