Louisiana Justice

So there is Al Sharpton, and here am I, crying in the truck while a man gets arrested.

In Jena, Louisiana, the Rev. Sharpton has come with busloads of protesters to decry the unfair application of the law along racial lines. Six black kids fought and beat up a white kid after months of being terrorized by him and others. Now the black kids face attempted murder charges, while the white kids go untouched by police. These teenagers are being tried as adults, and the phrase “Jena justice” is being tried out as a new reference to unduly harsh treatment of African Americans by the police and courts.

That this is wrong goes without saying. That this is unsurprising in the Deep South also, sadly, goes without saying.

The same week the massive protests are held in Jena, I am working in New Orleans, driving a box truck to pick up recycled building supplies. I back out of a parking space and into the front end of a red truck parked behind me. I hadn’t seen it, and though I don’t hit it hard, the sound of the truck hitting the plastic bug-guard is terrifying. I set the brake and leap out to inspect the damage.

From the other truck’s cab emerges a young man, visibly shaken. “I’m so sorry,” I tell him. “I didn’t see you. Were you in the truck? Are you OK?”

The man and I inspect his truck. The damage is minor. He nods. “I’m OK. Yeah. I was in the truck,” he says. “And so were my children.”

“Are they OK?” I ask.

He nods, and I can see him begin to relax. “Yeah,” he tells me. “They’re OK. The baby didn’t even wake up.”

Inside the truck are a 1-year-old boy and a 3-week-old baby. The little boy opens the door. “Hi,” I say. “I’m sorry I hit your car. You OK?”

The boy nods and looks at his father, then shyly shows me the toy truck he’s holding.

“I’m really sorry,” I tell the man again.

He nods and smiles. “It’s OK. I know,” he says.

The truck’s owner turns out not to be James, the driver, but his uncle. James calls his uncle, who calls the police to have them come out and take a report for insurance. Meanwhile, my co-worker, Ateven, and I call our work to report the accident, and they, too, call the police.

I walk back to where James sits, now joined by his partner, Erika. (The first names of James and Erika have been changed to protect their privacy.) James looks up from his cell phone. “My uncle called the police for some reason,” he says, shrugging apologetically.

I nod: “My work did, too.”

We settle in to wait for the police.

It is an hour and a half before they come, during which time James and Erika and Ateven and I talk. James and Erika talk about being exhausted. (“To be honest with you, I didn’t even see you hit me,” James says. “I had my head down for a minute. That baby had me up until 3 a.m.”) James says he works overnight stocking at Lowe’s. (“You like it?” I ask. He grimaces and says, “I gotta work tonight. And the Saints are playing, too.”) James’ uncle shows up and inspects the damage, then confers with James briefly before driving away.

I squint at him, feeling terrible. “Is he mad?” I ask.

James shrugs. “Let me put it like this, I’ll probably hear about it when I get home. My uncle is also my landlord, so I am sure I’ll hear about it from him and my auntie.”

I groan. “I am so sorry.”

James shrugs again. “It’ll be alright.” We watch his son crush ants on the sidewalk with his car. James swoops him up and over his head, and the child shrieks with delight.

Eventually a police officer pulls up. From Ateven and me, she asks for license, registration, proof of insurance. I find everything but a current registration, and instead give her the expired one in the glove box. From James and Erika, she asks for all that, then asks where they were going, whom the car belongs to, why did they have it, where did the children live, where do James and Erika live, where do they work. She takes the information and returns to her car.

After some time she calls me over. “Do you have current registration? This is expired,” she says.

I make a face. “Probably?” I tell her uncertainly, “but I don’t know where.”

She nods and says. “Well, you have the sticker on your plates to show you are registered. But you have to keep current registration in your vehicle.”

“I know,” I say. “I just started this job. I didn’t realize it wasn’t there.”

“So what happened?” she asks.

At this point I need to clarify some things. James and Erika are black, in their 20s, cleanly dressed. Ateven and I are white, slightly older, and filthy from work. The police officer is white, female, and maybe in her early 40s at most.

I tell what happened. “I pulled in. There was no one behind me. At some point he must have pulled in behind me, but I didn’t see him, so when I went to back up I hit him.”

The officer shakes her head. “Mmm-hmm. He told me he was already there. He said you hit him.” She says it as though she caught James in a lie.

I look at her, confused. “Yes,” I say. “I hit him. He pulled in behind me at some point, and I didn’t see him, so I backed into him. It was totally my fault.”

She nods. “Well, I’m going to have to give you a ticket, but I am going to give you the cheaper of the two I could give you. That’s all I can do for you.” She says this nicely, and it is clear she is trying to help me out. I thank her. She nods. “He is going to be sorry he called the police,” she says conspiratorially.

“What?” I say, alarmed. “He didn’t call the police. He didn’t do anything. I hit him. This isn’t his fault.”

The officer just shrugs. “You’ll see.”

I walk away from the car, feeling dread. James and Erika are both at their truck, on the phone. I tell Ateven what just happened. “The only thing that could make this worse,” I say, “is if now she arrests James for some reason.”

Ateven shakes his head. “He wouldn’t have sat here and waited for the cops if he had a warrant or anything,” he says. “I’m sure he’s fine.”

I am less sure. “But this is Louisiana,” I say. “People go to jail here for anything. You can go to jail here for a parking ticket. A parking ticket!”

Ateven shakes his head. “It’s probably nothing,” he says.

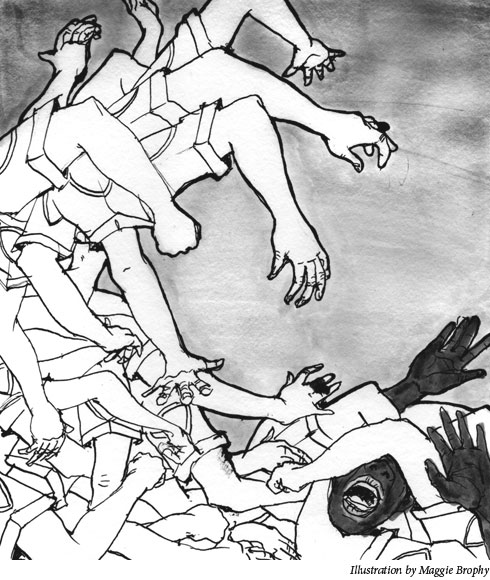

Twenty minutes later, the officer calls James and me to her. He and I trade one last look, eyebrows up, and smile at each other. The officer hands me a ticket and tells me I am free to go. Then she grabs James and handcuffs him. “You have a parking ticket you haven’t paid, and there is a warrant for you because of it,” she tells him, and begins to recite his rights.

“No!” I tell her before I can think. “Ma’am, no, you can’t do that. He didn’t do anything. He has a 3-week-old baby in the car.”

“The judge wants to see you,” the cop tells James. “That’s all I know. So you are going to go to jail.”

I can’t shut up. “Ma’am, no! No! He didn’t do anything. This was my fault!”

She says, “That’s between him and the judge.” She marches him into the police car. James doesn’t resist. His face has gone closed and hard. Then he is in the car, and I can’t see him. I turn and walk to Erika and the children.

She looks at me. “What happened?”

I start crying. “She arrested him. She says there is a warrant because of a parking ticket.” My hand is clutching the ticket, and I hold it over my mouth.

Erika frowns. “He paid that,” she says. The cop walks over, and Erika says it again. “He already paid that ticket!”

The officer shrugs. “All I know is, there is a warrant that says he didn’t.” She tells Erika where James will be taken and leaves.

Erika gets on her cell phone. I approach, ask if there is someone I can call, something I can do.

“It’s OK,” she says. “I’m calling someone.”

“You want me to wait with you until someone comes?” I ask. She shakes her head.

“It’s OK,” she says. “We’ll be OK.”

Later that night I call Erika. “Maybe I can go to James’ work,” I say, “and tell his manager it is my fault he’s missing work tonight, so he doesn’t get fired?”

Erika says, “I’m on the other line with the manager right now. I’ll call you back.”

An hour later she calls. “He’s not going to get fired. He had paid that ticket, we have a receipt. So I have to go down there tomorrow with the receipt, and then they will let him out.”

“Tomorrow?” I ask, incredulous.

“Yes.”

I ask her to let me know if there is anything I can do, and apologize again. Erika is unbelievably pleasant, considering I just brought such an afternoon of hell into their lives. “OK,” she says. “It’s going to be OK.” She thanks me for calling and hangs up.

It’s not like I just moved here. I’ve lived here nearly six years, and not in a bubble. I was here during Hurricane Katrina. I live in an African-American neighborhood. I went to Jena when I first heard about the six kids there, and marched through the town with their families. I grew up with an African-American best friend.

It’s not that I don’t know things are screwed up. It’s not that I have never experienced racism.

It’s that, in Jena, the cases were thrown out, and there seemed to be movement for the better, but in this broken city the brutal kick always waits for delivery to the next African American whom someone backs into. It’s that, as the white party, I became a vehicle for this unfair punishment. It’s that, if it had been me with the unpaid parking ticket, I would have had a finger shaken at me and nothing more.

It’s that I was powerless in the face of it, am still powerless in the face of it. It’s that Jena justice is Louisiana justice, which is United States justice. This man could have lost his job, his home, and his ability to provide for his children because of my accident and the officer’s disregard. It’s that the children of nice, hardworking, young black people have to watch their father get taken away in handcuffs by the same government that will punish them if they grow up angry and act out. It’s that, if I were James or Erika, I don’t think I could ever have had half the grace they had. It’s that all I can do now is offer myself again and again to these kind people who wish I would just leave them alone.

And I can tell this story, to anyone who will listen.

Alec Hamilton is a writer living in New Orleans.