Political Intelligence

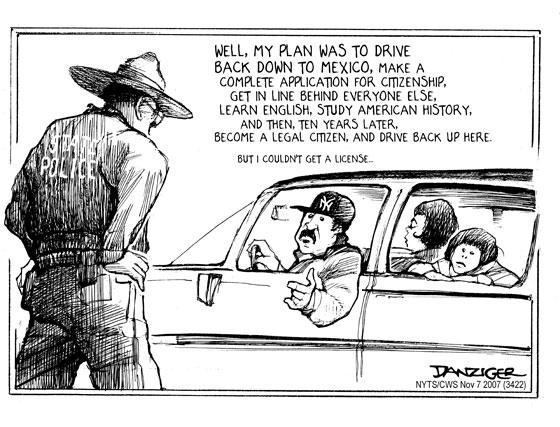

No Wall Will Stop the Wave

FENCING OVER THE FENCE

Tucked into the 2005 federal Real ID Act is a little-noticed provision, Section 102, that gives the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security unprecedented power to suspend any law that stands in the way of building a wall along the border. In late October, for the third time, Homeland Security chief Michael Chertoff used the act to waive statutes-19 in this case-protecting water and air, endangered species, migratory birds, and archaeological sites, among others. He did so after the Sierra Club and Defenders of Wildlife convinced a judge to issue a temporary restraining order halting work on a 2-mile section of fence that cuts through Arizona’s San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area. A district judge in Washington, D.C., agreed with the environmental groups that the government had failed to adequately assess the environmental impacts of the wall.

On November 1, the two groups amended their lawsuit, alleging that the Real ID Act violates the Constitution. According to the amended complaint, Section 102 “violates the U.S. Constitution’s fundamental Separation of Powers principles by impermissibly delegating legislative authority to a politically appointed Executive Branch official.”

Though centered on Arizona, the legal challenge has major implications for South Texas, where construction on the border wall has not yet started. A court victory for the environmental groups could derail Chertoff’s plans for Texas, says Scott Nicol, from Weslaco and a member of the No Border Wall coalition. “[Homeland Security] will have to comply with all our nation’s laws including the Endangered Species Act and the Migratory Birds Treaty Act,” he says.

Biologists and Texas border residents warn that the wall could deal a serious blow to the binational ecology of the Rio Grande Valley, the most biologically diverse region in the U.S. and an epicenter of migratory bird populations. The latest map of the wall shows 21 segments totaling about 70 miles between Roma and Brownsville. The wall would erase miles of riparian habitat, splitting the 90,000-acre Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge, a decades-in-the-making wildlife corridor and home to the spotted ocelot, of which only 100 remain in the world. The Sabal Palm Audubon Center in Brownsville would be sealed off from the rest of the United States, leaving this rare grove of palms stranded in a no-man’s-land. It would also damage the Texas economy. Ecotourism in the Valley brings in an estimated $150 million annually.

The Border Patrol says the wall will enhance the environment by deterring illegal immigration. But the fight has just begun. From Laredo to Brownsville, communities on both sides of the border have called on the Bush administration to abandon its plans to divide the region. Some mayors are even refusing to give the feds access to public land.

Privatization Pains

The walking wounded gathered in Porter, a small town north of Houston, on October 27. They shared two things: All had been injured in Iraq, and all felt they weren’t receiving the medical treatment and disability benefits they deserve. They weren’t soldiers, but representatives of the more than 100,000 nonmilitary contractors in Iraq. The meeting was the third by a loose national network of former civilian contractors held together by a Web site called www.americancontractorsiniraq.com. At least 917 contractors have been killed in Iraq, and more than 12,000 wounded, according to The New York Times, though precise statistics are hard to come by.

Most at the meeting were truck drivers, not the private contractors getting rich off the war or firing on cars along Iraqi highways. Of the 10 contractors who attended, three were injured in the same truck convoy in September 2005, and hadn’t seen each other since just after the attack. Some said they had earned around $84,000 a year hauling food and supplies to troops in Iraq-good money, but hardly a windfall. “These are not the Blackwater types,” says Jana Crowder, a contractor’s wife who runs the group’s Web site. “They’re not walking around in their ‘Terminator’ sunglasses.”

Art Faust, the 57-year-old retired trucker who organized the meeting, left his job hauling groceries around East Texas in 2004 to go to Iraq, where his son was already stationed as a soldier. Faust hired on with KBR Inc., the former Halliburton Co. subsidiary, and drove the dangerous roads between U.S. bases. His was the eighth truck in a convoy that came under attack. Despite being pinned down in his truck while the convoy took gunfire that killed three drivers, Faust miraculously wasn’t shot. Shaken by the experience, though, he left his job and came home feeling isolated and distant around his family. “I sort of came home feeling like I didn’t fit in,” Faust says.

While KBR’s insurance company, AIG Inc., has declined to cover Faust’s treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder, he has been helped by therapy he’s paid for out of his own pocket. His therapist, Sandra Dickson, spoke at the meeting about recognizing PTSD and the need to treat it like any other injury. Others at the meeting had similar complaints about their inability to receive care through insurance companies.

Chris Winans, an AIG spokesman, says more than 90 percent of the claims the company receives from contractors injured in Iraq are paid without any dispute, which he says is consistent with the rate for domestic claims. “There is not a product out there that achieves 100 percent customer satisfaction,” he says. “We’re very interested when our claimants feel they have been treated badly and want to help them.” Winans says it’s particularly difficult to diagnose PTSD, as opposed to a physical injury, but that half of the 200 PTSD claims AIG has received from contractors in Iraq were paid without dispute. “Of the rest, the problem is usually a lack of documentation,” Winans says.

Faust’s group hopes to help remedy that.

Bad Behavior

Fed up with years of inaction, on October 29 the county attorney for El Paso County asked state environmental officials to recommend that a criminal investigation be opened into ASARCO LLC. The copper mining company operated a smelter in the city for more than a century leaving a toxic legacy of lead, arsenic, and other metals (see, “Clean Up or Cover Up,” October 8, 2004). The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality has 45 days to respond. “Asarco’s past behavior is a constant repetition of environmental violations, failure to pay the penalties for those violations, failure to complete actions intended to correct past violations, a steady stream of excuses, and bankruptcy,” the letter to TCEQ states.

The complaint accuses ASARCO of failing to pay $30 million in cleanup costs and penalties ordered by the EPA and the TCEQ in 2004. ASARCO says the unpaid costs will be addressed in ongoing bankruptcy proceedings. The company, a subsidiary of mining conglomerate Grupo Mexico SAB, declared bankruptcy in 2005.

“This is not the sign of a multinational company really showing good faith, in my view, in meeting its obligations under environmental and health laws, and that’s why we have concluded, you know, enough is enough,” says José Rodriguez, El Paso County attorney.

The request also turns on allegations that ASARCO illegally burned hazardous waste in its smelter. New evidence emerged last year when the citizen group Get the Lead Out Coalition uncovered a document from federal regulators. In a 1998 memo, the EPA accused ASARCO and Encycle, a Corpus Christi-based subsidiary, of “extensive sham recycling” of more than 5,000 tons of hazardous waste in the 1990s. “This activity, plain and simple, was illegal treatment and disposal of hazardous waste,” the EPA concluded in the memo.

ASARCO officials have responded that the EPA’s charges have already been addressed in a 1999 civil settlement that was modified in 2004. Under terms of the settlement, the company agreed to remediation and to pay penalties of just under $20 million.

Meanwhile, ASARCO is seeking approval from TCEQ to reopen its El Paso copper smelter. In a perverse form of polluter logic, company representatives told state lawmakers earlier this year that revenue from the facility could help pay for environmental remediation. Despite a recommendation from two administrative law judges to deny the permit, TCEQ is allowing the company to fix deficiencies in its proposed pollution controls. And in the unlikely case that criminal charges are filed against ASARCO, the company could still receive a permit from TCEQ, says Neil Carman, clean air director for the Lone Star Chapter of the Sierra Club. Terry Clawson, a TCEQ spokesman, says “criminal convictions relating to compliance with requirements under the jurisdiction of the TCEQ” would be considered during permitting. A pending criminal investigation, however, has no effect.

Rodriguez says allowing ASARCO to reopen in light of its track record defies common sense. “The best predictor of future behavior is past behavior,” he wrote to TCEQ, “and ASARCO’s past behavior is cause for alarm on behalf of El Paso, for both their pocketbooks and their health.”

Home Alone

State Sen. Eliot Shapleigh (D-El Paso) calls it an approaching tsunami. In 2008, more than $300 billion worth of volatile subprime home loans will spike to higher interest rates nationwide, and a torrent of foreclosures will likely follow. In Texas, where subprime mortgages have glutted the housing markets of several cities, the effect may be severe.

Mortgage lenders grant subprime loans to homebuyers who don’t make enough money, or whose credit is too poor, to qualify for a standard mortgage. Subprime loans are typically adjustable rate mortgages that lure in homebuyers with ultra-low “teaser” interest rates that jump after the first two or three years. As the housing bubble expanded in recent years, the subprime market became catnip for lenders. But as the rates on loans spike, homeowners suddenly find they can’t afford their monthly payments. Foreclosure becomes almost unavoidable.

In August, nearly 244,000 homes were foreclosed nationwide, a 36 percent increase from July and a rise of 115 percent from the previous year, according to RealtyTrac, a group that compiles foreclosure data. Texas had the ninth highest foreclosure rate in the nation in August-a 36 percent increase from July.

Shapleigh believes that’s just the beginning. At nearly 40 percent, the border city of McAllen boasts the country’s highest percentage of subprime loans. Moreover, the nation’s top five subprime refinance markets-and seven of the top 10-are all in Texas. If the housing market in those cities crashes, the state’s economy could suffer.

“Texas could be the epicenter of this deal because of all the subprime lending in about six counties,” Shapleigh says. He says many Texans could lose their homes, and state and local governments could lose property tax income. He warns of a potential budget deficit for the 2009 legislative session.

A recent congressional report documented the potential economic cascade of a further crash in the housing market. The report, by the Joint Economic Committee of Congress, estimated foreclosures on 2 million homes with subprime mortgages nationwide by the end of 2008. The foreclosures could weigh down property values by more than $100 billion. That drop in value would deprive state and local governments of $917 million in property taxes, according to the congressional report.

The senator recently requested that Gov. Rick Perry call a special legislative session next spring to address a looming foreclosure crunch. In his letter to Perry, Shapleigh proposed that state officials encourage lenders to find alternatives to foreclosure. He also suggests increased state funding for nonprofit housing counselors, and requiring that borrowers receive some counseling and education before taking out a risky subprime loan.

The governor’s office has said Perry has no plans to convene a special session, though he is “monitoring the situation.”