For Bolaño, No Divine Miracles

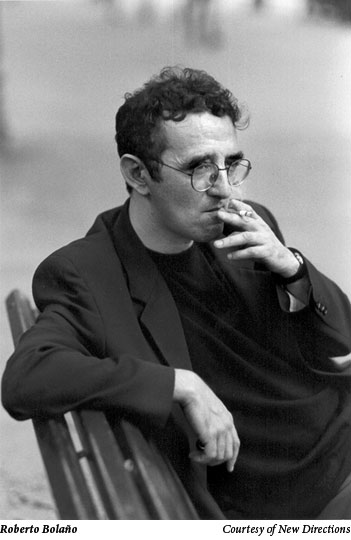

Since his death in 2003 at age 50, Chilean-born writer Roberto Bolaño seems to have skipped over the typical stages of an emerging literary cult figure and moved quickly toward canonization. A novel, a collection of short stories, and three of his novellas, including Amulet, have been translated into English since his death, and more works are set to follow.

His writing puts an end to the assumption that Magic Realism (and its marketable knockoffs, typified by the popular works of Isabelle Allende and Laura Esquivel) is the dominant form of exported Latin American literature. Bolaño denounced Gabriel Garcia Marquez as a kind of cultivated sellout who was “thrilled to know so many presidents and archbishops.”

“He was famously dismissive of most Magic Realist writers,” Natasha Wimmer, who has translated his work for Farrar, Straus & Giroux, said in an interview. “He claims some of their forefathers, like [Jorge Luis] Borges and [Julio] Cortazar, and he retains a kind of Latin American identity-a sense of solidarity with the Latin American past, a sense of hailing from a global backwater-that other writers of his generation have taken pains to shed.”

There are no divine miracles or anthropomorphized landscapes in Bolaño’s books. Instead, he chases modern stories of perception and epiphany married with a raw attention to urban exile. His vibrant, open-ended social critiques, Wimmer notes in her essay Roberto Bolaño and The Savage Detectives, have “received the kind of acclaim that marks a shift in the landscape.”

Almost all his characters-skywriting fascists, book-reviewing priests, and misguided activists-are writers, and there are no apologies. An eerie mix of melancholia and political poesy binds readers to Bolaño’s guilty men and women of letters.

Bolaño grew up in a series of Chilean backwater towns. His father was a truck driver and amateur boxer; his mother taught math. Bolaño was a dyslexic kid, an adolescent with chronic anxiety. He was a dropout, a book thief, and a heroin addict before settling into happy family life. He was a man who read everything, from Cervantes to junk sci-fi. He watched horror movies when he couldn’t sleep. He worked a string of menial jobs, from night watchman to jewelry seller, and without a desk wrote on the floor.

He eventually came to fiction, but not before denouncing it, swearing to never write novels. Bolaño was a poet first. At 23, wild-haired and wearing aviator goggles, he read from his manifesto, Leave It All Again, which challenged poets to take to the road, jump the cozy world of coffee shop-bookstores, and engage in actual encounter, inaugurating the dada-inspired movement Infrarealism.

It might have seemed like big talk from a young and impassioned idealist, but Bolaño took to the task. Already a kind of nomad, having moved from Chile to Mexico because of political upheaval, he spent his life on a trek that led to Paris and Spain, and to his opinion that Latin America was somehow initially planned as a kind of mental asylum for Europeans.

Bolaño started writing fiction after the birth of his son Lautaro, entering state-sponsored story contests and sending the same work with different titles to multiple contests. Winning multiple times for the same piece was in some way a stab at financial stability.

Though he did not fall into writing fiction easily, Bolaño won immediate critical acclaim for his work, garnering the coveted Romulo Gallegos prize with the 1998 publication of The Savage Detectives.

Reading the novella By Night in Chile, or certain digressions in Savage Detectives, Borges and Cortazar are obvious influences. Bolaño delights in mapping damnable policies and is urgently concerned with the immediate world. His rough and mannered compositions leave a reader with the feeling that the man is clumsy with elegance. Perhaps this has something to do with Bolaño’s nods to pop culture and his rendering of the politics of his time.

Chris Andrews, who has translated Bolaño for Harvill and New Directions, agrees that “‘clumsy with elegance’ is a neat formula. It captures something original in Bolaño’s work: a deliberate roughness combined with imposing eccentric erudition.” In an interview, Andrews adds: “We are used to writers being (a) rough and raw and responsive to the ‘real’ (i.e. the extra-literary) or (b) elegant and erudite and preoccupied with style. We are not so used to a writer who uses an elaborate system of literary references to grapple with the real, while declining to smooth off the surface of his own work.”

By the time he wrote Amulet, Bolaño had largely given up poetry for prose (going so far as to omit verse in Savage Detectives) and found success in that arena. Amulet in particular seems to lament the sacrifices made for poetry.

Amulet is the story of Auxilio Lacouture, a Uruguayan refugee who settles in Mexico City before the revolution and tends to the poets she admires, cleaning for the elder lyricists Pedro Garfias and Leon Felipe. The masters get on her case for trying to do away with accumulated dust, for “dust and literature have always gone together,” Bolaño writes. Art must court not only its own decay, but the falling away of the world that might appreciate this very decay. Auxilio realizes that “the dust was never going to go away, since it was an integral part of the books, their way of living or mimicking something of life.”

Auxilio is preternaturally suited for this understanding, as her sense of time and place is malleable: “I came to Mexico City in 1967, or maybe it was 1965, or 1962. I’ve got no memory for dates anymore, or exactly where my wanderings took me; all I know is that I came to Mexico and never went back.” Auxilio doesn’t bemoan the nuances of her life as a literary domestic. She is grateful to serve, and she is a poet as well. Her acts of aesthetic altruism make her a “mother of Mexican poetry.”

Amid the sudden rush of a military raid at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Auxilio is on the toilet on the fourth floor of the faculty of philosophy and literature, reading Pedro Garfias. Fortuitously, she becomes a standout resister in the raid: “I saw people with books in their hands, people with folders and typed pages spilling onto the ground, bending down to pick them up, and I saw people being dragged out of the faculty building or coming out covering their noses with white handkerchiefs, which were rapidly darkening with blood.” What looks like a light, survivor-type fable becomes unhinged and racks toward the ephemera of every light and break in light. Professors kill themselves for love. Poets are changed by war. Misanthropic painters embody the dialogues of the gods. Young people take themselves seriously, and the future of literature is crooned to Auxilio by a weak but eternal word-spirit. Anton Chekhov will be reincarnated again and again, with no stay of longevity. Kafka will again be read underground.

This heroine is haunted. In her open-hearted observation, she is permitted the perspective of the cunning seer. Her burden is to annex language and know its ends and releases: “The children, the young people, were singing and heading for the abyss. I raised a hand to my mouth, as if to stifle a shout, and held the other hand out in front of me, fingers extended and trembling, as if trying to touch them.”

This novella is, in fact, an elaboration of a scene in Savage Detectives, a sprawling novel of competing narratives that looks back with humor and disillusion at the author’s days of youth and Infrarealism.

Bolaño must have felt that the story of Auxilio Lacouture, based on real-life Uruguayan poet-exile Alcira who went mad hiding out for 10 days during a 1968 military raid, needed its own plane. “I think the character was calling out to him for more space and time,” Andrews says. “She was an emblematic character strongly associated with poetry, youth, and Mexico City.” Bolaño’s work was a rhizomatic beast at this point. “There was no reason why he had to stop there; any of those digressions could have spawned new works. When you start looking at how the expansions were done … it’s dizzying. Even if Bolaño had days when he was on fire and days when he was smoldering, it seemed that from the mid-nineties up till his death lack of narrative ideas was never a problem.”

Andrews sees that: “In Amulet, and elsewhere, Bolaño is paying tribute to all the idealists who commit themselves to a field where the chances of symbolic and financial gain are very slim indeed. I think he felt that he betrayed the cause, in a way, by going over to prose. He admires the sacrifices made for poetry while lamenting them: health, career prospects, financial security, respectability. Auxilio Lacouture is a saint in the religion of poetry, because she gives up all those things, and her own poetic ambitions as well, content in her role as the mother of Mexican poetry. This is an aspect of Bolaño’s work that is likely to seem exotic in North America, where poetry is not taken so seriously outside the universities, but I think it would be a mistake to see poetry primarily as a metaphor for something more general.”

Amulet is dedicated to Mario Santiago Papasquiaro, a friend and Infrarealist co-conspirator of Bolaño’s immortalized in Savage Detectives. Andrews concedes that Amulet “is an indirect elegy for Mario Santiago, another emblematic figure: the pure poet, the poete maudit, Bolaño’s unlucky double. Bolaño must have thought, sometimes, ‘That could have been my life too’: obscurity, poverty, addiction, early death. They were born in the same year, 1953, and in the end they died only five years apart.”

Wimmer, who also has translated writers such as Mario Vargas Llosa and Pedro Juan Gutierrez, says of her work on Savage Detectives: “I definitely felt from the beginning that this was a translation that would be required to stand the test of time, and I did my best to use language that wouldn’t date. I try to do that anyway. But it’s also true that the better the novel, the easier the translation tends to be. To some degree, a great novel carries the translation-the better the book itself, the better the reader feels the translation to be.” Andrews, an award-winning Australian poet, has a similar view: “Overall, Bolaño has a fairly robust style: not that it’s easy to translate, but it’s powerful and distinctive, so that in a sense the task of the translator is not to get in the way, or, rather to transmit the impact as fully and as directly as possible.”

Amulet‘s prose is not instructive or pushy. Bolaño wryly and blithely accepts the demands of art. Art wants every damn thing and may offer back only the understanding that it needs every damn thing. Amulet seeks not to subvert, but to find waspy succor in the recognitions of art’s unchanging burden. Amulet and the yearning represented in its pages is an anthem to march by, to carry as one stands. There is a ring of eternal return in these pages. Souls that make lyrical sense of the universe are a constant in Bolaño: as old as the Earth, as old as the desire for eulogy that accommodates all that is fine.

Despite what may appear a tendency-in his characters and in his life-toward cynicism and judgment directed at an arbitrary canon, Bolaño was obsessed with his literary afterlife. Two of his better short pieces, “A Literary Adventure” and “Dance Card,” find their gravity in this worry. There are rumors that he might have postponed the liver transplant he needed so that he could see that his last book, 2666, was ready to be considered a good draft, reasoning that he could start the revisions after an operation that never came.

Roberto Ontiveros is a freelance writer living in New Braunfels.