Scotland, Texas

I don’t remember whether you could see the house from the highway. It was about 4 miles east of town on a low rise, under a glaring sky at the end of a dirt road. It had plowed fields behind it and, in front, a long slope down through eroded pasture studded with prickly pear and prehistoric-looking sandstone formations. I remember one shaped like a fountain, with a shallow bowl a 5-year-old boy could climb up into and rub with a rock to create a self-perpetuating sandbox. The pasture ended at the brushy shores of muddy old Lake Arrowhead.

I don’t remember whether you could see the house from the highway, but you could see it from a fishing boat on the lake, because one afternoon not all that many years ago, Clay and I came out of Deer Creek, and our eyes were blinded by the glint of sunlight on a tin roof.

“There’s y’all’s old house,” Clay said.

I shielded my eyes and looked. I hadn’t remembered it being so small or so close to the water. I seemed to remember the pasture sloping for several hundred yards before reaching the shore. I said as much to Clay, who had never stopped fishing this lake. “The lake was low back then,” he said. “It hadn’t even finished filling up all the way.”

Muddy old Lake Arrowhead indeed. It hadn’t occurred to me that, when I was 4, 5, 6 years old, when my family lived there, the lake was not much older than I was.

In the evenings, my father came home from work and picked me up-I’d been waiting-and we drove through the pasture to the johnboat we kept tied up in the brush. It was my job to push us off, trying not to get my feet wet. As the flat-bottomed boat glided away from the shore, my father gave a crank on the rope, and the outboard Evinrude coughed to life in a cloud of oily blue smoke. We maneuvered among ghostly trees slowly drowning in the shallows, out into the open water of what had been, once upon a time, the Little Wichita River.

And the fish we harvested from that lake! Never mind that I could rarely stay awake past the second trotline. The bottom of the boat writhed with slick, whiskered channel cat. It was all we ate, the two and a half years we lived there. Anything with scales was thrown back. Snapping turtles were decapitated on the spot, their armored bodies sinking and their stump necks pumping gouts of blood. For “pollies”-the poison-finned, hard-headed little mud cats-a special indignity was reserved: the polly stick. You stood in the boat with a sawed-off paddle, tossed the fish to a short height, then whacked it like a baseball on the descent. The sound was as final as a verdict if you connected. If you didn’t, the fish had a story to bring back to the tribe.

“The polly stick,” my wife asked me. “You’re making that up, aren’t you?”

No.

Red-ant beds sprouted in the scorched dirt road like angry pimples. I caught horny toads by the fistful and set them among the teeming ants and squatted at a distance; the horny toads flattened out and looked back at me with sunken eyes. The ants changed course.

Grasshoppers the color of the dirt clicked out from the dust in front of my feet and sailed forward on pale yellow wings opening like paper umbrellas. I smashed the grasshoppers with a toy shovel against the hard, flat road; the yellow wings fanned out.

Plastic army men in combat positions squinted around dirt clods where the plowed field crumbled away to the road. I made quiet gunfire noises with my mouth. I repositioned the survivors.

We had a Water Wiggle, an orange, cowbell-shaped apparatus with a simplistic, smiling face scrawled onto it, that Mama hooked up to the hose in the backyard. My sister and I put on our shorts and danced and hopped barefoot among the grass burrs while the Water Wiggle rose and shimmied before us like a friendly cobra, hissing water.

In an abandoned tin shed I found a kitchen knife with a yellowed bone handle. I kept it for years. One day-I don’t remember when-I realized I hadn’t seen it in a long time and likely never would again.

Some evenings he didn’t get home in time. Some evenings he got home in time, but instead of going to run the lines, we drove down to the Bluegrove highway and crossed the low bridge spanning Deer Creek, where old men and women wearing wide-brimmed hats fished from lawn chairs beside the road. We turned north at the blinking light governing the intersecting highways that constituted the inexplicably named settlement of hard-drinking German Catholics-Scotland-passing two liquor stores, the Exxon Full-Serv, Frances’s Cafe. The Cowboy Country Club, run by a woman named Josephine, was a few hundred yards up the highway. From the caliche parking lot, I could hear the muffled laughter and music from the jukebox inside. “I won’t be long,” he said.

But he would be. Eventually I’d slip inside. If the shuffleboard table wasn’t being used, I’d linger at one end and sight down the polished boards filmed with sawdust, sliding the heavy pucks along, not understanding the game or what the goal was. But I liked how the smooth glide and slow twirl of the pucks along the wood surface felt like the johnboat drafting clear in the shallow water near shore after it had cleared the rocky ground.

Finally somebody would notice me, and there’d be the exaggerated joking laugh: “Uh oh! Gene’s in for it now!”

“Don’t you take him there anymore! Not in there with that redhead!” my mother screamed after we got home. My little sister would wail and wail, and after a while I would join her, my mother running onto the porch calling my father’s name, and my sister and I crying like the world’s end as we heard his pickup driving away in the night.

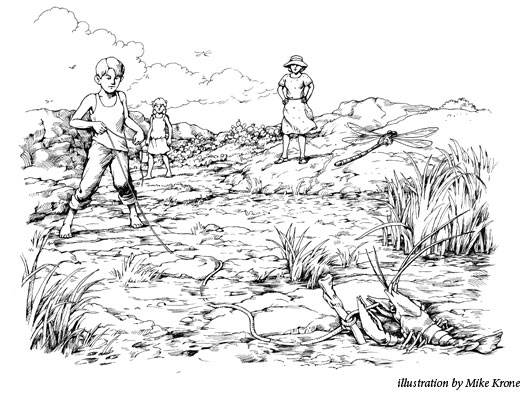

The crawdad tank wasn’t really any kind of reservoir most of the time since it retained water only after a heavy rain, and then only briefly. It caught the runoff from the hill, true, and during heavy downpours, from the window of the attic where my sister and I slept, you could see the water coursing in small rivers down the series of rocky crevices lining the hillside, emptying into that mudhole. After the weather cleared, you could walk down there and see the tank full again, hear the sudden explosion in the frog population, maybe even see a baby turtle no bigger than a 50-cent piece stranded in a water-filled hoofprint farther up the bank, treading water in an endless slow twirl. The crawdad tank after a rain was like one of those overnight boomtowns from the twenties, a free-for-all. For the next several days, you could walk down there in the mornings and see the busy footprints of raccoons and coyotes and bobcats and the remnants of last night’s feast: crawdad claws, eggshells, mussels broken apart, a few feathers, a killdeer running along the water’s edge dragging her wing, pretending to be injured so as to lead you away from her nest in the scrub.

Most of the time, however, the tank was a semi-arid bog. First the water would soak away until only a few isolated pools remained, and then that would soon be gone too. A blistery pudding skin would develop. As the days grew hotter, the tank emitted a fetid smell. Dragonflies flourished, feeding on something nobody else could see. The surface of the tank would bake slowly until it took on the hue of the surrounding pasture, cracking into segmented tiles whose edges would curl up, allowing the sun to begin baking the next layer below. Still, no matter how dry it got or how long it stayed that way, if you poked a stick through the crust, no more than a half inch down you’d find the ground cool and wet and firm. In that eternal miasma, below their mud towers crumbling like abandoned cities, the crawdads lived on, waiting for the next thunderstorm.

After the rains we trooped down there, we three-my mother, my sister and I-down that rocky pasture, carrying twine, bacon, a chicken bone, baloney, whatever we had in the house a crawdad might like, and, optimistically, a 5-gallon bucket.

Crawdad fishing. It’s delicate work, requiring great patience, tedious for anyone but the very young and the very lonely. You tie the bait to a string and toss it into the water, not more than a couple feet off the bank. You wait for the slow tug, the crawdad backing away with your line. You match its tug with one of slightly greater force, pulling the line in slowly, an inch at a time, between forefinger and thumb tip. The crawdad might let go, but not if you do it slowly and evenly enough. The trick is knowing when to jerk the line. If the crawdad sees you, it will let go immediately. So you keep an eye out for the place in the muddy water you think it will emerge, and when you see the first whiskery antenna break the surface, you snap the line like cracking a whip. If it is done well, the crawdad can’t let go, and is launched out o f the water and onto the bank behind you. Pick it up just behind the pinchers, using thumb and forefinger; the pinchers stretch up like the arms of robbed stagecoach passengers.

Later in the afternoon the bottom of the bucket was barely covered, but we picked up our gear and traipsed back up the slope to the house, my mother telling me to hold my little sister’s hand and watch for snakes, which I did with great vigilance. On the cement pad beside the cistern, she picked one crawdad at a time from the bucket and shook loose those clinging to it; they dropped like refugees from the runners of the last helicopter out. She snapped the tail from the living body, squeezed the cold meat from the shell, extracted the fecal tube that lay along the spinal ridge, and dropped the little white nugget of meat into a bowl. The rest of the crawdad went into the yard, or the cistern, or back into the bucket to be cannibalized. The handful of tail meat in the bowl, the point of all this, she fried in cornmeal and bacon grease in a skillet on the stove. We waited for Daddy to come home.

That little family I was a part of didn’t stay together long. A few weeks into second grade, we moved back to Young County, the home I didn’t remember, where I would spend the rest of my childhood and adolescence, and which I would leave for good at 18.

So it turns out that the time in Scotland, on that muddy lake, had been destined to be temporary. How was I supposed to understand that when I was 4, 5, 6 years old? Within a year or so after the move, my father had pretty much stopped coming home, but still I would stand outside until after dark, on the dirt road in front of another rented farmhouse, waiting to see the headlights I hoped were his.

As it turns out, my wife is from Scotland, but I mean the country this time. We live in Houston. So we’re both a long way from home.

Our children are not. It’s something I remember when I come upon my son, not yet 5, wearing glasses he’s worn almost half his life, crouching beside the flower bed staring at something-bug, leaf, worm-that only he can see because only he is seeing it for the first time. I remember, with intermittent bursts of clarity and haze, the look on my young mother’s face as she watched my sister and me pulling in our crawdad lines, and on my son’s behalf I feel the old familiar regret: Whatever he’s looking at with such intensity and concentration, however completely he has memorized it, he’ll never see it again. Or when I hear my little girl, just turned 2, singing to her dolls as she puts them to sleep, in one long row, while the refracted light of the backyard pool through the patio door unsettles the shadows around her on the carpet. I don’t see that light because it’s a light that exists only in childhood; I am seeing only the diluted memory of it. The infinite splendor and mystery of the world for them starts here, I remind myself, as does all the rest. In those moments I marvel at their innocence and beauty, even as I worry how fragile all this is, how easy it would be to screw it up, and how I still wouldn’t put it past myself.

Wade Williams, a former James A. Michener Fellow, lives in Houston.