The Best Government Money Can Buy

The Money Men: Capitalism, Democracy, and the Hundred Years’ War Over the American Dollar

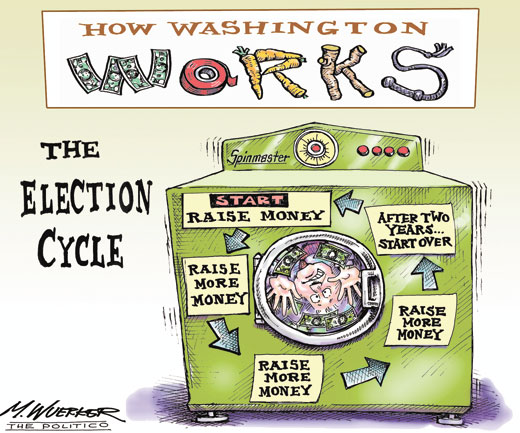

Though I would like to think we would do away with the Electoral College and let the people directly elect the president, my fear is that the system would be replaced with an auction, with the candidate raising the most campaign money emerging as chief executive.

Imagine a constitutional convention (“brought to you by Geico”) resolving the following (Amendment XXVIII): “The president and vice president shall be chosen among those candidates who have demonstrated a proven ability to raise funds during the previous four years. The president shall be the candidate who has successfully raised the most money, net of bank loans, matching grants, and other internal transfers, including that of family trust funds. The vice president shall be chosen by the political action committee that has disguised the most donations as spontaneous, small gifts from its membership. In the event of a tie, an eight-hour telethon, conducted live on the floor of the House of Representatives, will determine the winner.”

I thought wistfully of the Electoral College-that gathering of wise men and women who ensure that democracy does not get out of hand-when the press seized on the Federal Election Commission’s first-quarter 2007 fundraising summary as though the presidential campaign was a variation on mutual fund results. Hillary Clinton raked in $26,041,107, confirming her bona fides as a candidate. Barack Obama and Mitt Romney proved their political wisdom by raising, respectively, $25,665,688 and $20,737,149. Other candidates’ chances and competencies were ranked according to cash flow. Those who could not even pull together $500,000, such as Dennis Kucinich and Tommy Thompson, were dismissed as unworthy. Why have an election if money means nothing?

Who has paid tuition at the Electoral College is one theme woven into The Money Men, the latest book from H. W. Brands, a prolific American historian and the Dickson Allen Anderson Centennial Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin. Brands is a felicitous writer, whose well-regarded books include biographies of Benjamin Franklin, Andrew Jackson, Woodrow Wilson, and Teddy Roosevelt. Brands is also the author of Lone Star Nation: The Epic Story of the Battle for Texas Independence. He has written extensively about America’s colonial interventions (from the Philippines to the Middle East) and the Cold War, including an appraisal of why Lyndon Johnson failed to nail Ho Chi Minh’s hide to the barn door.

Brands’ writing occasionally lapses into hagiography when he reflects on the patriotic machinations of robber barons. In this book, for example, Jay Cooke (the merchant banker extraordinaire who brought us the Panic of 1873) and J.P. Morgan (lender of last resort to numerous administrations) come across as altruistic sellers of savings bonds.

According to Brands, from the revolutionary period until World War I, “a single question vexed American politics and the American economy more persistently than any other. … The question was the money question. In simplest form it asked: What constitutes money in the United States? Gold? Silver? Paper currency? Bank notes? Checks? This central question raised subsidiary questions. How much money shall there be? Who ought to control it? To what ends?” The American political system became one long, endless dispute about whether the country should have a central bank, a national currency, federal debt, and a gold standard.

The question of capitalism’s compatibility with democracy, which divided the likes of Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton, remains fundamental to American politics. At the moment, the consensus is that the American economy has a cloudless future, in part because it has been spun off to the investment banking business. But don’t kid yourself: When you see the likes of Robert Rubin and Henry Paulson (both ex-Goldman Sachs) running Treasury, clothe them in your mind with the whiskers and waistcoats of a Morgan or Jay Gould. With the House of Goldman installed in Washington, recall the thoughts of Cooke’s father, who during the Civil War saw his sons and their placemen well appointed in and around the Lincoln administration. According to Brands, father Cooke reflected: “Now is the time for making money. … The door is open.”

Hamilton and Jefferson were contemporaries from the mid-1770s until 1804. During the Revolutionary war, Hamilton was an officer on Washington’s staff and led a bayonet charge at Yorktown. He was in Philadelphia the summer of 1787 during the constitutional convention and co-authored The Federalist Papers. John Adams called him “the bastard brat of a Scottish peddler” and later resented the way Hamilton manipulated President Washington. But everyone respected his financial acumen.

At times Jefferson and Hamilton worked well together, and a dinner in Philadelphia led to the federal assumption of state debts in exchange for the relocation of the Capitol to the banks of the Potomac. They served together in Washington’s first cabinet but disagreed, almost violently, on the principles of American government and economy. Nevertheless, it is thanks to Hamilton that Jefferson, and not Aaron Burr, became president in 1800. (After Burr killed Hamilton in their famous duel, he reflected: “Had I read Voltaire less and Sterne more, I might have thought the world wide enough for Hamilton and me.”) Jefferson said his rival was “amiable in society, and honorable in all and duly valuing in private life, yet so bewitched & perverted by the British example, as to be under thoro’ conviction that corruption was essential to the government of a nation.”

According to Brands, Hamilton’s vision of a strong central government dominating the national economy is triumphant today in Washington. He carried the early debate on whether the United States should be capitalist with some democracy, or democratic with some capitalism. (The Constitution makes no reference to either system.) Hamilton, for example, convinced the government to redeem Revolutionary War-era debts at par (what Jefferson described as Hamilton’s gift to the “stock-jobbing herd”), delivering a windfall to early speculators who had snapped up financial paper at pennies on the dollar. He set up the first Bank of the United States, maintaining, as Brands quotes Adam Smith, that a central bank could be a “great engine of state.”

A hard-money man, Hamilton believed banks should only lend against specie in their vaults (not against Enron-like inflated balance sheets). Unlike Jefferson, he believed the federal government had the right and obligation to issue money and incur debt. He was the first proponent of deficit spending. By contrast, Jefferson thought “banks more dangerous than standing armies” and saw the future of America in its villages and small farms, not in the assets and liens of its moneyed class. Jefferson wrote whimsically (in part about himself) that Virginian planters were “a species of property annexed to certain mercantile houses in London,” and resented having a mortgage over both himself and the democracy.

The Bank of the United States, the only federally chartered bank, lasted until the presidency of Andrew Jackson, who went after it as though it were snake loose in the Oval Office. Brands quotes a conversation between Jackson and his vice president: “The Bank, Mr. Van Buren, is trying to kill me. But I will kill it!” In particular, Jackson despised the bank’s president, Nicholas Biddle, for his pretensions toward oligopoly, his deference to capital, his bribery of certain legislators (including Daniel Webster), and, no doubt, the spread he took on government deposits.

An uneasy relationship had always existed between the Bank of the United States and the government. Brands describes its initial public offering, in Hamilton’s day: “Thirty members of Congress-more than a third of the total membership, and half of those who voted in favor-became charter shareholders.” Biddle, however, thought government finance too important to be left to the people: “We believe that the prosperity of the Bank and its usefulness to the country depend on its being entirely free from the control of the officers of the Government, a control fatal to every bank which it ever influenced.”

A product of the emerging West, Jackson saw Eastern capital behind every bank column and determined to rid the democracy of money changers. As Brands recounts: “Jackson believed the Bank undermined democracy by creating a monopoly of money. Of the Bank’s twenty-five directors, only five were answerable to the people. The rest served the interests of capital.” He withdrew the government’s money and vetoed the bank’s charter extension. Biddle retaliated by tightening the money supply and driving the country into the depression of 1837. He scoffed at Jackson’s threats (“It has all the fury of a chained panther biting the bars of his cage. It is really a manifesto of anarchy.”) and called in his congressional markers. In the end, though, the national bank was broken, or as Jackson railed: “The government will not bow to the monster.”

Jackson’s agrarian capitalism, which included an unsolicited bid for Texas, lasted only until the Civil War, which Brands describes as a victory for central bankers and bond dealers. He writes: “The planters lost their slaves; the capitalists won control of the national government. The capitalists created a national currency, a national tax code, a national banking system, and a national system of credit …” Brands’ conclusions cast Gettysburg in the guise of a hostile takeover.

Lincoln might have preferred to save the Union with eloquent proclamations and pithy letters to his generals. But by December 1861, the Union was insolvent. To prosecute the war, Lincoln was forced to take the U.S. off the gold standard and issue an early form of junk bonds. Jay Cooke’s genius, according to Brands, was “to convert bond sales from a wholesale business to a retail one.” Cooke and his agents practically sold them door to door. Cooke believed in the Union cause and may well have been a war profiteer with a human face. But he also belongs in the pantheon of private contractors, from the Revolution’s Robert Morris to Halliburton in Iraq, who have outsourced American wars with rigged bids and hidden commissions, all taken in the name of patriotism.

The Civil War shaped the economic argument in the United States for the next 50 years, a contest between the interests of Wall Street and those of the West. The battle for the American bank account divided those who put their full faith and credit in paper money from those who believed in gold.

The gold standard was a legacy of the California rush and the British Empire, which, like the United States today, thought banks (or at least a reserve currency) ruled the waves. Nominally, during Reconstruction, American paper money was redeemable against a fixed ratio to gold. (Higher prices for gold drove down the value of the dollar, helping exporters; weaker gold in relation to the greenback was better for importers.) But gold, despite its magical luster, was still a commodity, like pork bellies, and vulnerable to corners and manipulation, something practiced with gusto during the administration of Ulysses Grant.

By the 1870s, the altruistic Civil War bond salesmen had become railroad speculators and political insiders. They included Jay Gould, who attempted to corner gold. Brands describes his motives: “His immediate purpose was what he had said all along: to depress the dollar enough to get the crops moving and keep his railcars full.” In this instance, the financially gullible Grant smelled a rat and sold off government gold reserves, breaking the bubble.

The ensuing panic of 1873 again emphasized the Hamilton-Jefferson fissures in the economy between gold traders on Wall Street and the farmers of the Great Plains, for whom gold’s periodic deflations were ruinous. Beyond the Mississippi, it was long felt that, “By stealing its specie, the capitalists of the northern seaboard sucked the life out of the South and West.” Little wonder that William Jennings Bryan emerged from the prairie, as Brands writes, preaching “the gospel of silver.” With money tied to something other than the inside trades of merchant bankers, both farmers and the democracy might not be nailed to a cross of gold.

According to Brands and other historians, the American economic wars that started with the Bank of the United States ended with the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, which established an independent central bank with the power to regulate the money supply. In effect, Hamilton’s heirs won. In theory, the economy would no longer be the province of amateur politicians, but have on call the kind of financial savvy that J.P. Morgan brought to the table when he routinely saved markets (and the country) from extraordinary popular delusions and the madness of crowds.

Admittedly, the Fed and the Hoover administration made a hash of responding to the 1929 stock market crash-they cut spending, raised taxes, and increased tariffs. Since then, according to the folklore of capitalism, the altruistic and independent Fed has avoided panics and ushered in numerous eras of good feeling, not to mention the sustained stock market rally that began in 1982. In this brave new world, we are all Hamiltonians, if not bond traders for Goldman Sachs.

Overlooked in the euphoria that has turned the American economy into a Speculator’s Ball is the extent to which the democracy has been reduced to a hedge fund, leveraged to the same interests that Jackson went after with a stick. According to the annual reports of the Bush administration, the economy has gone from strength to strength because of the pluck and luck of its entrepreneurs, the self-regulating mechanisms of its markets, and the thrift of its citizens. My feeling is that the game is unchanged since it was practiced by the Jays (Cooke and Gould): Financial self-interest is dressed up as patriotism, and citizens are being taken for a ride (perhaps on one of Morgan’s railroad trusts).

At almost every level, what is sustaining the U.S. economic miracle is Hamilton’s beloved debt. The federal government balances its books with paper laid off to Asian bondholders under the Faustian bargain that they buy our securities and we buy their exports. Domestically, the lender of last resort is not the Fed, but the U.S. consumer, sadly as innocent about speculators as Abraham Lincoln.

In the last six years, to pump liquidity into the market, the government has not only run record deficits but laid off further indebtedness on its citizens, who have been forced to borrow against the equity in their houses just to pay for college. Mortgage debt is now almost $11 trillion, up from $6 trillion in 2001. More than half of this debt floats with interest rates, leaving borrowers exposed to a credit squeeze. The same is true of consumer credit, which in the last 10 years has increased from $1.1 trillion to $2.4 trillion. (Popular T-shirt: “I can’t be overdrawn. I still have more checks.”) No wonder candidates for president are judged as collection agents.

So long as the carousel of indebted prosperity keeps turning, consumers can buy a new car every few years, and the executives of major investment banks can pay themselves salaries and bonuses that routinely exceed $15 million annually. The winners from this great wheel of fortune are the financial intermediaries-banks, investment houses, hedge funds, and stockjobbers-that issue credit cards, securitize mortgages, collect monthly payments, package bonds to pension funds, and process payments at the mall. (As Mark Hanna crowed when William McKinley was elected: “God’s in his heaven; all’s righ

with the world.”)

When the merry-go-round stops, the well paid executives will have retired to Boca Raton, but citizens will be left holding IOU bags that put their houses financially underwater and their government hocked to the Chinese. At that point, leasing the country to Hamilton’s speculators will not look like much of a deal.

Matthew Stevenson is a contributing editor to Harper’s Magazine. His books are available at www.odysseusbooks.com. His e-mail address is: [email protected]