Long Past Enough

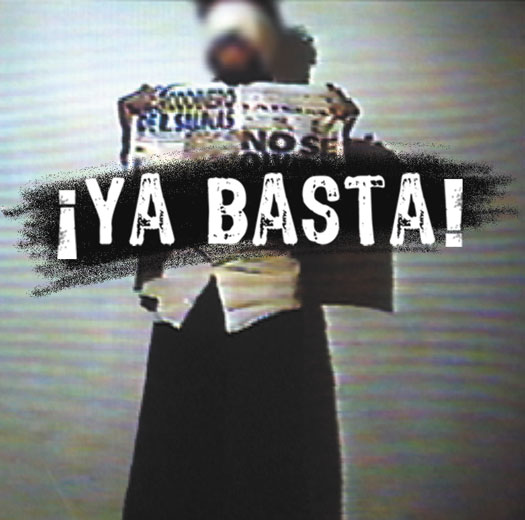

¡Ya Basta!

Every day in Mexico there are an estimated 10 kidnappings. ¡Ya Basta! is an intimate documentary that captures the harrowing stories of six. It’s also a film about an antiquated judicial system incapable of dealing with a sudden and vicious wave of crime. And hopelessly corrupt police. And a nascent victims-rights movement. And efforts to reform the police. In short, this new movie by Austin-based psychologist-psychoanalyst, filmmaker, author, musician, and University of Texas professor Ricardo Ainslie is an ambitious work. While Ainslie’s curiosity and search for solutions to what may be intractable problems muddies the 72-minute film, ¡Ya Basta! often rivets viewers with penetrating insights and leaves behind disturbing questions. For anyone wanting a glimpse of modern Mexico’s difficulties, Ya Basta is a must-see.

Mexico leads the world in kidnapping. The ultrarich have responded with machine gun-toting bodyguards, and walls topped with surveillance cameras and barbed wire. Unable to penetrate these defenses, kidnappers have targeted the middle class and even the poor. Traditional kidnapping-spirit the victim to a safe house and demand money-has been supplemented with new forms of extortion. Secuestro Express is the term Mexicans use to describe cases when a victim is grabbed, usually in a taxi, and forced to withdraw money from their bank account, sometimes over successive days to foil ATM limits. Then there is virtual kidnapping, whereby a phone call threatening violence and including a few choice personal details convinces victims to hand over cash. It all adds up to an explosion in violent crime during the past decade.

Ainslie, who grew up in Mexico, decided to make the documentary after visiting Mexico City for the first time in years and discovering the chaos into which it had descended. Family members and friends all had horror stories about assaults. Those who could afford them showed up at neighborhood cafes with bodyguards. Local press attention chronicling the widespread violence, combined with several high profile murders and kidnappings, galvanized citizen outrage. But most folks in the United States were unaware of what was going on. People need to know this is happening, Ainslie thought.

The filmmaker began tracking down kidnapping victims. Among those chronicled in the film, two stand out. Each story on its own would have made a compelling film. Pedro Galindo is mostly featured sitting on a wooden chair against a blank wall, a sparse setting mirroring his matter-of-fact recitation of a true tale of terror. Americans accustomed to tearful television confessions might have trouble connecting to this stoic small businessman, who was grabbed out of his car and held for 29 days. Ainslie cuts between Galindo and his wife, Maria Elena, as they describe how the kidnappers demanded money the family didn’t have. Galindo coolly narrates how the kidnappers sawed off one of his fingers to show they meant business, leaving it for the family in a plastic bottle on a roadside. Suddenly, the shocking fact that three of his fingers are missing comes into sharp focus. Galindo’s ordeal only ends when he is rescued by the A.F.I., or Agencia Federal de Investigaciones, a new police force modeled after the FBI.

In the second story woven through the film, Eduardo Gallo, an accountant, tells about the abduction of his 25-year-old daughter Paola, murdered despite the payment of a ransom. Gallo realizes the investigation by prosecutors is riddled with errors and uninvestigated leads. He puts his life on hold, closes his business, and dedicates the next two-and-a-half years to hunting down the kidnappers. “I couldn’t allow the kidnapping and murder of my daughter to become a statistic,” he says.

Gallo is a worthy proxy for exploring myriad problems in the Mexican judicial system, but he is underutilized in the film. Ainslie depends on a variety of experts to detail how Mexican justice-which dates to the Napoleonic era and has no juries, no detectives, a glaring lack of resources, and rampant corruption-cannot be depended upon. In fact, it is something to be avoided. The A.F.I is offered as one partial, possible solution.

The film offers a menu of reasons for the explosion in crime. Mexico’s dire poverty and lack of social mobility is an obvious answer. Ainslie manages to score an interview with an actual kidnapper, who appears to be in police custody. The kidnapper offers few insights, but does say, “Currently kidnapping is almost, as they say, in vogue because it brings money … brings a lot, you know?”

One of the more interesting insights into Mexico’s turn toward anarchy parallels the situation in Iraq. Under the 70-year-old dictatorship of the PRI political party, Mexico’s government was authoritarian, but kept its corruption systematic and controlled. Once Mexico became more democratic, it was no longer clear who was in control. Accountability vanished, and a system of social strictures along with it.

The film ends with a 2004 protest rally where a million people marched through Mexico City under the banner, ¡Ya Basta! (Enough Already). After Pedro’s kidnapping, Maria Elena Galindo helped form an organization called Mexico Unido Contra La Delincuencia, which sponsored the march. Despite the impressive turnout, Ainslie’s subjects acknowledge little has changed. As the film ends, he tells us that at least one subject of the film has left the country. The file containing original evidence of Paola Gallo’s murder has mysteriously disappeared, and the kidnappers Gallo rounded up are in danger of being set free. At the end, one is left wondering whether, since Mexico’s ruling class can afford to exempt itself from the threat of violence, the country has truly reached its ¡Ya Basta! moment.