Selective Memory

The Ultimate Insider Tries to Hoodwink us Again. Twice.

Work Hard, Study…and Keep Out of Politics! Adventures and Lessons from an Unexpected Public Life

The Iraq Study Group Report:The Way Forward – A New Approach

The ultimate crony is back on center stage. James A. Baker III, the single most powerful and most recognized non-elected politico in the U.S., has emerged again to play power politics. And once again, Baker is using his influence to hoodwink the American people. This time, he’s doing it on multiple fronts.

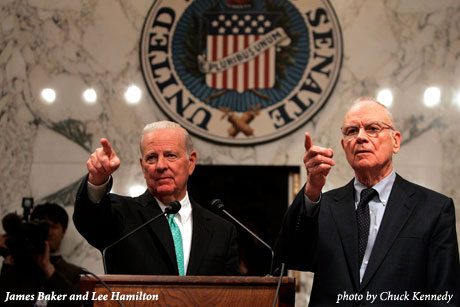

The first hoodwink comes from Baker’s new book: Work Hard, Study… and Keep Out of Politics! Adventures and Lessons From An Unexpected Public Life, released in October. The second is found in The Iraq Study Group Report: The Way Forward-A New Approach, the much-ballyhooed document published on December 6. The release of the two books—and particularly, the attention given to the Iraq Study Group (ISG) report—has led to Baker’s nearly constant presence on TV news, political talk shows and in the newspapers.

And while Baker is, once again, receiving adulatory coverage from much of the mainstream media, the books he has produced are notable as much for what they omit as what they include, and those omissions expose the fundamental dishonesty of both efforts.

Before delving further into the sanitized version of history Baker presents in his book, and the ISG recommendations, it’s essential to give the man his due. James Addison Baker III is the Clark Clifford of the modern era—the presidential adviser who never strays far from the corridors of power. Clifford, the ultimate Washington insider, advised presidents from Harry Truman to John Kennedy. Under Kennedy, he served as the head of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, the group with access to all of America’s most-secret intelligence. In 1968, Lyndon Johnson appointed Clifford as his defense secretary. Clifford was on the job in the Pentagon during North Vietnam’s Tet offensive of early ’68, a move that caught U.S. forces off guard and brought the fighting to the streets of Saigon. (In July 1969, after Richard Nixon took office, Clifford wrote that the war in Vietnam was lost and that “Nothing we might do could be so beneficial… as to begin to withdraw our combat troops… we cannot realistically expect to achieve anything more through our military force.”) Clifford parlayed his government service into a sizable personal fortune as one of Washington’s most prominent lawyer-lobbyists. It’s exactly the same business model that Baker has followed.

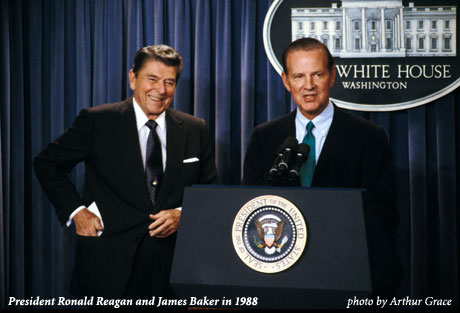

Baker’s career at the forefront of presidential politics began in 1976, when he ran Gerald Ford’s unsuccessful campaign to stay in the White House. Four years later, he managed George H.W. Bush’s primary campaign—an effort that led to Bush’s selection as Ronald Reagan’s running mate. Despite being perceived as a foe by some members of the Reagan camp, Baker became a key player in Reagan’s 1980 campaign. After Reagan won the White House, Baker became his chief of staff. In 1985, Baker left to become Reagan’s treasury secretary, a job he held until he quit to run Bush’s presidential campaign in 1988. When Bush was elected, one of his first acts was to appoint Baker to be his secretary of state. Baker served in that job during one of the most tumultuous periods in recent world history, a time that included the breakup of the Soviet Union and the first Iraq war.

As secretary of state, Baker demonstrated his toughness while trying to negotiate peace between the Arabs and the Israelis. Like the elder Bush, Baker believed that there was no chance for peace in Palestine if the Israelis continued to build settlements in the Occupied Territories. So Baker issued an ultimatum: The U.S. would freeze all loans to the Israelis unless the construction of new settlements stopped. This led to an outcry from the Israeli government and the pro-Israel lobby in the U.S. But Baker refused to budge. Since that time, he has repeatedly stated that the Israelis’ settlements in the West Bank (which continue to be built) “make peace impossible.”

After the elder Bush’s failure to win re-election in 1992, Baker moved back to Houston and began taking jobs that allowed him to cash in on the enormously lucrative intersection of business, legal work, politics, and diplomacy. He became a senior partner at Baker Botts, the law firm founded by his great-grandfather. He became an equity partner and senior counselor at the Carlyle Group, the huge private equity firm. He joined corporate boards, including that of Houston Lighting & Power (now known as Reliant Energy Inc.), and Electronic Data Systems Corp., the Dallas-based information-technology giant. (One of his fellow board members at EDS: Dick Cheney.) Baker signed up to lobby for Enron Corp. on deals in Kuwait, India, Turkey, Qatar, and Turkmenistan. And through all of that work, he helped drive business to Baker Botts. How much business? That’s hard to say, but James A. Baker IV, the son of the former secretary of state who is now the managing partner of the firm’s Washington, D.C., office, said a couple of years ago that his father had been “reserved in his business development activities, but it would be disingenuous to say it hasn’t been an asset.”

In fact, since Baker III joined his family’s firm, and particularly since George W. Bush became president, Baker Botts has become one of the world’s most influential law firms. It has become a major player in the energy business, particularly in Russia, where it has worked for the Kremlin-controlled gas giant, Gazprom. The firm now has offices in Austin, Dallas, Houston, Dubai, Hong Kong, London, Moscow, New York, Riyadh, and Washington. Baker’s job as a rainmaker at Baker Botts probably pays him several hundred thousand dollars per year. But it’s doubtful that his partnership interest in the firm accounts for a substantial percentage of his wealth. More likely, he’s made it by peddling his status as an insider with the Carlyle Group. According to one published account, Baker’s stake in the private equity firm (which he left in 2005) was worth $180 million. Baker has consistently refused to discuss his finances. In late 2003, I caught up with Baker during a black-tie benefit for the think-tank that was named for him, the Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University.

After Dick Cheney, the event’s featured speaker, had finished declaring that Saddam Hussein had “an established relationship with al-Qaeda” and that thanks to the American invasion, “Iraq stands to be a force for good in the Middle East,” I was finally able to buttonhole Baker, who had refused my requests for an interview. I asked about the $180 million figure. “That’s bullshit. You print that,” he told me. Asked how much his Carlyle stake was worth, he replied, yelling, “That’s for me to know and you to not know” and refused further questions.

Despite Baker’s high-profile jobs for the Bush administration, none of his financial information is publicly available. While Baker was working for the Bush White House as its representative on Iraqi debt, he was deemed a “special government employee,” a status that shields his finances. It’s up to the White House general counsel’s office to determine if Baker has any conflicts of interest.

While Baker’s first book, The Politics of Diplomacy: Revolution, War & Peace, 1989–1992, deals almost exclusively with his tenure as secretary of state, Work Hard is a personal reflection, a look back at his family life, his life in politics, and his upbringing in one of Houston’s most prominent families. It was a privileged childhood. Baker relates that when the University of Texas played football against Texas A&M, his grandfather, James A. Baker I, known as the Captain, “often took us to the game in a private rail car arranged through one of his railroad clients.” His family’s aristocratic ties inevitably led to fundraising and politics. And Baker explains how the elder George Bush consistently encouraged him to get into the political game.

Much of the new book focuses on Baker’s work for Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and his long relationship with, and fondness for, the elder Bush. Baker provides his spin on the Florida recount fight in 2000. “Florida is largely remembered as a legal battle, but in my opinion it was every bit as much a political battle, and we may have understood this point better than the other side.” Baker takes credit for the Bush camp’s decision to fight the battle in federal court and the U.S. Supreme Court. In Baker’s view, Bush and his team prevailed for several reasons: “…the law was on our side. And yet again, we still had more votes than the other side—537 to be exact.” Naturally, Baker omits facts that don’t fit his narrative, the most important being his consistent misrepresentations of the facts during the Florida fight. For instance, on November 11, 2000, Baker told a packed news conference, “The vote in Florida has been counted, and then recounted. Gov. George W. Bush was the winner of the vote. He is also the winner of the recount.”

Baker was making it up. He knew full well that the recounts had only just started. The day before Baker delivered his sound bite, the Gore campaign had requested recounts in at least four counties, but only two of them had actually begun recounting their ballots. But Baker stuck to that sound bite, and in doing so he helped assure that Bush won the political battle in Florida.

While Baker’s views on Florida are revealing, and some of the vignettes from the Reagan era are entertaining, (in one photo caption he declares that Nancy Reagan “was always an ally”) Work Hard is fundamentally dishonest. Here’s why: It completely omits one of the most important historical events of the Reagan era and the last few years of the 20th century: the savings and loan disaster.

Baker—perhaps more than any other single American—bears substantial responsibility for the loss of more than $100 billion in taxpayer money during the savings and loan meltdown of the late 1980s. Baker served as Reagan’s treasury secretary from early 1985 to August 1988, a time when it was clear that fraudsters and con artists were looting banks and thrifts all over the country, but particularly in Texas. Baker worked to downplay the magnitude of the growing disaster for obvious reasons: Admitting the scope of the mess would make Texas look bad, it would make Reagan look bad, and in doing so it would hurt the political aspirations of the elder George Bush, who was running for president in November 1988.

Evidence of a massive cover-up can be seen in Baker’s testimony before a House Appropriations subcommittee on April 19, 1988. During that appearance, Baker said that the $10.8 billion that had recently been appropriated to the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corp. to clean up the S&L disaster was all that was needed. That amount of money, Baker told the panel, “will provide FSLIC with enough resources to handle the problems of the industry over the next three years.” Baker went on to say that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., which insures banks, had plenty of funds. “There are some commercial banks that are having problems, but the FDIC’s fund, currently with about $18.6 billion in it, should be able to handle these problems.”

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of Baker’s statement. Few people in America had more information about the troubles facing the nation’s financial system than Baker. He had dozens of staffers whose jobs were to monitor and assess the health of the nation’s financial systems. As early as 1986, Baker and other Treasury Department officials knew that the cost of the cleanup would be $50 billion or more. In fact, at about the same time that Baker was testifying before the House, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board was putting out its own estimate on the cost of repairing the nation’s S&L industry. That group estimated that resolving the problems at the 500 worst S&Ls in America would cost $21.8 billion—more than twice what Baker was claiming. Furthermore, by the time Baker testified, America’s S&Ls were racking up losses at the rate of $1 billion per month.

Even Baker’s own deputy, George D. Gould, the Treasury Department’s undersecretary for finance and the Reagan administration’s top policy-maker for banking and finance, was saying more money was needed. In May 1988, the month after Baker appeared before the House subcommittee, Gould told the Associated Press that $20 billion was “probably not enough.”

Not only did Baker hide the extent of the cost, he agreed to get rid of Edwin Gray, the competent and aggressive head of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board. In 1986, Gray, a political appointee, launched an aggressive investigation of Texas S&Ls, including Vernon Savings, which was being looted by a group of bandits led by Don Dixon. In 1987, rather than appoint Gray to another four-year term, the Reagan White House replaced him with M. Danny Wall, a bureaucrat whose only real job qualification was that he’d been the Republican staff director of the Senate Banking Committee when it drafted the Garn-St. Germain law, which deregulated S&Ls and opened their vaults to fraudsters and looters in the first place.

In June 1985, just a few months after he moved to Treasury, Baker was warned by the head of the FDIC, William Isaac, that the “problems of the thrift industry are of such proportions that they will soon overwhelm” the FSLIC. Rather than deal with Isaac’s ominous warning, Baker ignored it.

In my book, Cronies, I wrote about the S&L mess and Baker’s role in it. I quoted William Black, an attorney who helped clean up the scandal-ridden industry while working for the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation and, later, as the deputy director of the Office of Thrift Supervision. Black told me that the Reaganites were “willing to do the most outrageous, unprincipled and dangerous things to maintain the cover-up” of the S&L disaster. And, said Black, Baker was one of “the centerpieces of this strategy.”

To be fair, Congress shares the blame for the S&L meltdown. Jim Wright, the Democratic speaker of the House from Fort Worth, worked hard to prevent federal regulators from cracking down on S&Ls in Texas. And his role in obstructing investigations into various S&Ls contributed to Wright’s fall from power. On the other side of the Capitol building, the Keating Five, a group of senators that included 2008 presidential hopeful John McCain, ran interference on behalf of disgraced S&L boss Charles Keating, the chairman of California-based Lincoln Savings and Loan. But none of those congressmen and senators was the secretary of the treasury. None of those men had their signatures on American greenbacks. None of those men had the power to appoint aggressive regulators to delve into the unfolding S&L disaster. Baker did. Yet he did nothing.

For the record, 1,169 savings and loans in the United States failed. Texas had the most failures, 237. That’s more than twice as many as any other state. In 2000, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation issued a report that said thrifts with total assets of more than $500 billion had failed. The bill for taxpayers on the S&L disaster, according to the FDIC, is some $124 billion. That sum does not reflect the entire bill. To pay for the S&L bailout, the federal government sold bonds. By the time those

bonds are finally retired in 2020 or

o, the total cost of the S&L mess will likely approach $300 billion.

Despite those numbers, despite the magnitude of the S&L mess, despite the fact that he was on the job during the worst of the fraud and looting, none of this information appears in Work Hard. In fact, the words “savings and loan” don’t even appear in Baker’s book.

A similarly flagrant omission is evident in the work of the Iraq Study Group. The bipartisan panel’s report has some useful ideas, including convening a meeting with some of the other key players in the Middle East, especially Iran and Syria. It also concludes that the U.S. “cannot achieve its goals in the Middle East unless it deals directly with the Arab-Israeli conflict and regional stability.” Yet it also offers ideas that have already proven to be nearly impossible to achieve, namely the creation of a reliable Iraqi security apparatus. The report says the Iraqi government should “accelerate assuming responsibility for Iraq security by increasing the number and quality of Iraqi Army brigades” and that the U.S. should increase its efforts to train the Iraqi army. But that process simply hasn’t been working. The Iraqi army cannot even meet its own logistical needs, much less work as a cohesive fighting force in a nation riven by Sunni-Shia hatred.

One other suggestion from the ISG that exposes its startling grasp of the obvious are recommendations 62 and 63, which, boiled down, can be summarized thusly: Iraq should reform its oil sector, expand production, and stop the corruption that plagues the country’s most important industry.

Pardon the use of the vernacular here, but there’s only one word that fits: Duh.

Iraq’s oil sector has always been the key. As energy economist and professor of economics at Ohio Northern University A.F. Alhajji has rightly declared, “Whoever controls Iraq’s oil, controls Iraq.” The U.S. never had enough troops in the country to control the oil. And that has meant that since mid-2003, the Iraqi oil sector has been on the down escalator toward disaster. Like many earlier analyses of Iraq, including those done by the neoconservatives at the outset of the war, the ISG contends that Iraq could increase its oil output to as much as 3.5 million barrels of oil per day—if only there were better security. And there—as Mark Twain once wrote—is “the bare bodkin.” Without security, more oil production is impossible. And without more oil production, the country can’t afford more security. Oil has always been the key to Iraq’s recovery from the corruption that typified the Saddam Hussein era. But during my visit to Kuwait in mid-2006, and in my discussions since that time with contractors who have worked in Kuwait and Iraq, it’s clear that the chances for reform are almost nil. Chaos reigns within the Iraqi oil ministry. Corruption rules the country’s motor fuel market. In August, the Washington Times reported that some service stations in Baghdad had two queues: one for regular customers and another for those paying bribes.

There are plenty of other ways to deconstruct the 79 recommendations included in the ISG’s report. But like Baker’s book, Work Hard, the report is most notable for what it omits. Just as the S&L disaster is missing from Work Hard, the ISG report lacks a simple declarative sentence that addresses the fundamental question: Should America stay in Iraq or leave?

The members of the ISG had access to some of the smartest people in Washington. It had researchers, former CIA officials, and others to help them understand the dimensions of the war and the problems that the U.S. military is having on the battlefield. The group surely heard about how roadside bombs are savaging the American military and how, despite billions of dollars invested in various technologies, changes in tactics, and years of effort, the military still can’t solve the problem. On the day the report was released, 13 American soldiers died in Iraq, eight of them killed by roadside bombs. There was plenty of other data to show how dire the situation has become. About 100 Iraqis are dying every day. The U.S. military, despite nearly four years of deployment, still doesn’t even control Baghdad. Anbar province, in western Iraq, is out of control. In the south, near the critical oil export terminals at Basra, Iranian influence is increasing.

Despite all these facts, Baker and his cronies on the ISG couldn’t bring themselves to state the obvious: that America has lost the war in Iraq and it must begin its retreat. The most forceful statement that the ISG could muster was that if its recommendations are followed, then the U.S. could “begin to move its combat forces out of Iraq responsibly.”

Of course, the ISG’s report may ultimately do some good. It might force George W. Bush to temper his faith-based foreign policy with a dollop of reality. Baker may, by applying the right pressure in Congress, allow for some negotiations with America’s foes in the region. Baker may be able to convince the younger Bush of the need to deal with the Israeli-Palestinian question.

Regardless of whether the ISG report is accepted or rejected, Baker has made the most of it. With the release of Work Hard and the ISG report, he has polished his reputation and guaranteed that his legacy will stand apart from that of George W. Bush. He has assured that he will be known as the foreign policy realist, the one who sees the world as it is, unlike Bush and the neocons, who view the world in the way they want it to be. Baker has, once again, fulfilled his duty as the family’s consigliere and done his best to help the Bush Dynasty out of a jam.

Unfortunately for the U.S., unfortunately for Iraq, unfortunately for all of the American soldiers who have died or been wounded in the second Iraq war—a war that Baker opposed because the U.S. lacked an international consensus—it appears that not even the mighty James A. Baker III can rescue George W. from this mess.

Austin-based Observer contributing writer Robert Bryce is working on his next book, Petroleum Soldiers, which will be released in fall 2007.

Baker, Baker Botts, and the Bushes: A brief history (sidebar)

2006: George W. Bush asks Baker to lead the Iraq Study Group, which is charged with finding a new strategy for the U.S. in Iraq.

2004: The younger Bush taps Baker to join his re-election campaign to negotiate with the campaign of Democratic nominee John Kerry over the rules and format for the presidential debates. Baker’s counterpart in the Kerry campaign: Vernon Jordan, who later serves in Baker’s Iraq Study Group.

2003: George W. Bush taps Baker to negotiate debt relief for Iraq, calling his job a “noble mission.” Baker is designated a special governmental employee by the White House, a move that allows him to avoid public disclosure of his financial holdings. Among Baker’s main stops: Saudi Arabia, which holds more Iraqi debt than any other country. While Baker was visiting Riyadh, lawyers from Baker Botts were representing Prince Sultan bin Abdul Aziz, the Saudi defense minister (now the country’s crown prince), in a lawsuit brought by survivors of the victims of the 9-11 attacks.

2000: Baker managed the Florida recount, assuring the White House for George W. Bush. A key to Baker’s success: his ability to tap the legal talent at Baker Botts.

1992: Baker gives up the only job in government that he’d ever really wanted—secretary of state—to take over George H.W. Bush’s foundering re-election campaign.

1991: Baker Botts lawyer Robert Jordan starts working for George W. Bush after the Securities and Exchange Commission inquires about Bush’s sale of stock in Harken Energy Corp. A decade later, after the younger Bush wins the White House, Jordan is appointed U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia.

Nov. 1988: About three weeks after George H.W. Bush is elected, the outgoing Reagan administration admits that the savings and loan mess will cost taxpayers more than $100 billion.

Aug. 1988: Baker takes over the elder Bush’s faltering presidential campaign against Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis.

Apr. 1988: As treasury secretary, Baker leads concerted effort to downplay the magnitude of the growing savings and loan debacle.

1980: Baker manages George H.W. Bush’s presidential campaign. That leads both men to prominent jobs in the Reagan administration.

1975: Baker works as undersecretary of commerce in the Ford administration.

1972: Baker acts as the 13-county chairman for Richard Nixon’s Houston-area Committee to Re-elect the President.

1964: George H.W. Bush makes his first run for the U.S. Senate, with Baker as a key advisor.

1962: George W. Bush gets his very first job, in the mailroom at Baker Botts in Houston.

1959: George H.W. Bush moves to Houston from Midland and quickly meets Baker. The two become tennis partners at the Houston Country Club. About the same time, lawyers from Baker Botts begin handling Bush’s legal work for the initial public offering of Bush’s drilling firm, Zapata Off-Shore.