Las Americas

The Many Mexicos de Don Felipe

Amid all the shoving, shouting, and whistling, and despite the banner proclaiming him a traitor to the Republic, on the morning of December 1, Felipe Calderón managed to enter the Mexican Congress—through the back door. He swore to uphold the Constitution, grabbed the presidential sash, fastened it over his right shoulder, and was out the back door again in less than five minutes.

Later that afternoon, Calderón spoke before a decidedly more receptive audience of party loyalists, government officials, and the international and business elite at the National Auditorium. “I assume the presidency of the Republic with the legitimate mandate to serve the nation as chief of state and head of the government,” he proclaimed, adding that he was aware “of the complexity of the circumstances.”

For those who were counting, it was the third time in less than 24 hours that Calderón had assumed the presidency—beginning with a bizarre midnight ceremony featuring his soon-to-be predecessor, Vicente Fox, the incoming cabinet, and a couple of poker-faced, exceedingly young-looking military cadets that was broadcast live on Mexican television.

As to the “circumstances” in which the 44-year-old lawyer, former energy minister, and lifelong (from the crib) National Action Party, or PAN, político took office, they are indeed complex. Calderón starts his presidency with just a 0.56 percent edge over his leading opponent in the July 2 elections, according to the federal electoral court’s opaque and contradictory decision issued in September, following two months of protests.

On November 20, Calderón’s main opponent, former Mexico City Mayor Andrés Manuel López Obrador, held his own inauguration and launched his “itinerant presidency,” promising to visit 2,500 municipalities throughout the republic by the time the magic year of 2009 rolls around (midterm elections and the eve of the 100th anniversary of the Mexican Revolution in 2010).

Beyond the weak mandate and political deadlock, Calderón must contend with an unprecedented spate of organized crime-related killings, particularly in his own home state of Michoacán.

Most complex of all is “the problem” that Fox had vowed to solve before December 1—the ongoing political, social, and economic crises in the southern state of Oaxaca, where decades—if not centuries—of pent-up social neglect have been inflamed by a troglodyte governor and a political system intent on criminalizing social dissent.

One of the poorest states in Mexico, Oaxaca has more indigenous residents than any other state, with 16 different ethnic groups, a majority of municipalities that follow usos y costumbres (loosely translated, the traditional system of unpaid local responsibilities), and a significant indigenous movement firmly convinced that the laws, institutions, and practices of the current political regime do not meet the needs and aspirations of much of the population.

For generations the state has exported its workers. NAFTA has further decimated the countryside, prompting an even greater exodus of Oaxacans.

The region has a history of strong social movements and can point to three governors ousted in 60 years. The city of Oaxaca itself is one of Mexico’s great treasures, home to several of the country’s finest artists and photographers, filled with museums and galleries, street musicians and gifted artisans. For all its vibrancy, Oaxaca steadfastly remained in the hands of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, and a particularly anachronistic strain of the party at that. As a result, all state entities—the legislature, courts, even the state human rights commission—have taken their cue from the governor.

Ulises Ruiz became Oaxaca’s governor in December 2004, after the nation’s highest electoral court upheld what was widely considered a fraudulent election.

Even in a state that had not been blessed with a spate of good governors, Ruiz was decidedly different. “Different because he was worse,” says Omar Angel Pérez, a 30-year-old human rights activist from the Isthmus of Oaxaca who now lives in Austin.

The new governor quickly set about destroying beloved city landmarks. He turned the government palace into a museum that could be rented out for private functions, initiated controversial and costly construction projects that benefited family and cronies, and targeted human rights activists and others, including journalists critical of his administration. In July 2005, the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists criticized the Oaxacan state government for orchestrating a blockade of the office of Noticias, a newspaper that had supported Ruiz’s opponent. Members of a pro-government union—who did not work at the newspaper—camped outside the building for several weeks, confining the paper’s employees to their office. Finally, a group of masked intruders—reportedly carrying sticks and pipes—forced their way into the building, destroying computers and furniture and forcing the employees to leave. Officials from the state attorney general’s office were with the intruders, a Noticias reporter later told the CPJ. A flock of state police officers lingered outside.

In September 2005, Pérez met with Ruiz to talk about severe environmental problems in the isthmus, including contamination caused by Pemex, Mexico’s state-owned oil company. Ruiz was using a police quarters on the outskirts of the city as his office. “Never mind coming here and calling me a repressor,” the governor told him. “We still haven’t gone after you—yet.”

That all-or-nothing approach was on display during annual negotiations with the teacher’s union, a kind of Kabuki dance that for the past 26 years has brought thousands of teachers from throughout the state to the city of Oaxaca every May.

Ruiz decided that the protests and downtown encampments damaged the city’s image and decided to stop them. At 4:30 on the morning of June 14, police entered the camp at the Zócalo, beating and kicking the sleeping teachers and their families, spraying them with teargas and pepper spray, demolishing the camps as a helicopter buzzed around and around the plaza, launching teargas canisters.

The Oaxacan Human Rights Network later took testimony from witnesses and victims. A representative account:

A helicopter began to fly around and the teachers, absolutely terrified, came running toward the door of the house to take shelter in the patio. About 60 teachers. Some of them had been gassed; they were given water, wet cloths and asked not to leave, but the helicopter saw that there were many compañeros in the house and kept flying around and filming the whole area. With all that noise, my children couldn’t sleep. The gas got into some of the rooms, so I took the children to the patio to show them to the helicopter—so that they could see that in this house there were children, families. So that somehow it would touch their hearts and they wouldn’t keep spraying those gases.

“After that, the whole thing took a different direction,” says Emiliana Cruz, a doctoral student in linguistics at the University of Texas at Austin, who still owns a small café in Oaxaca. In 1989, when she was 18, her father was murdered. He had been working on land rights and environmental issues for their community in the southern mountains of Oaxaca and was on his way to an indigenous rights forum in Mexico City. “My father was murdered by one of the wealthiest families,” she says. “There was never an investigation. That’s my case,” she says, matter-of-factly.

But it’s one of many. Just days after the attack on the teachers, hundreds of indigenous rights and other organizations joined with the teachers to form the Asemblea Popular de Pueblos de Oaxaca, known as the APPO. Years of pent-up frustrations, the fervor of myriad causes, melded into a single chant: “Fuera Ulises!” “Out with Ulises!”

The governor had spent much of the year campaigning for the PRI presidential nominee, Roberto Madrazo. On July 2, for the first time in Oaxaca’s history, the PRI’s presidential candidate was overwhelmingly defeated throughout the state. The events of June 14 were still vivid. And the APPO was growing.

“A lot of people were not participating with the teachers,” Cruz explains, “but when the APPO comes into the picture it became very strong. It’s not just a problem of teachers anymore, but all the sectors of society that didn’t have a space to come together.”

In a state where the population is 3.5 million and the circulation of the largest newspaper, Noticias, is just 20,000, radio is the way to get the message out. On June 14, one of the main targets of the attack on the teachers was Radio Plantón, literally Sit-in Radio, a pirate radio station critical of the government. The following day, students took over the university radio station, Radio Universidad, to replace Radio Plantón. Weeks later a group of “intruders” destroyed Radio Universidad’s transmitting center. In response, a group of APPO women briefly took over state-run and commercial radio and TV stations. When Radio Universidad was back up and running, a series of anonymous announcers took calls from people who had always felt excluded from the media. La Doctora Bertha, a 58-year-old grandmother and medical professor, instructed her listeners on the best home remedies for tear gas. In between rounds of Chilean protest songs and her cheery sign-off—”Hasta la Victoria, Siempre!“—she would remind her listeners that this was a peaceful resistance movement, un movimiento pa-cí-fi-co.

Meanwhile, Ruiz set up his own pirate radio station and Internet site, Radio Ciudadano, citizen radio, an electronic witch hunt. Citizens could call up and identify people they considered to be threats to society, problems that needed to be taken care of. Photos and contact information were posted on the Internet site. Alarmed by the spiral of violence and presence of paramilitaries, on August 25, Amnesty International issued a warning: “Illegal militias in Oaxaca are participating in the security forces ‘dirty work.’ The current crisis in Oaxaca is the result of systematic failure and unwillingness to deal with the state’s underlying problem and to protect people’s most basic human rights.”

But the crisis in Oaxaca would have to wait for the crisis in Mexico City to pass. In late August, López Obrador supporters were camped out downtown in anticipation of the final decision of the federal electoral court. The congress was surrounded by military troops in anticipation of Fox’s final state of the nation address—which he ended up delivering in Los Pinos, the Mexican White House on September 1, after the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), blocked him from stepping up to the congressional podium. On September 5, the elections court issued its decision upholding Calderón’s victory by approximately 234,000 votes out of more than 41 million cast. On September 16, several hundred thousand López Obrador supporters amassed in the Zócalo. Vowing to never recognize the Calderón presidency, they proclaimed López Obrador the legitimate president of Mexico.

Meanwhile, Calderón tried taking a tip from Bill Clinton—or perhaps Dick Morris, who had reputedly advised the PAN campaign. He borrowed a phrase or two from López Obrador and proclaimed that poverty was Mexico’s number one priority, while appointing an orthodox economist and former top IMF official to head his economic team. After losing time with the protracted post-electoral protests and litigation, he began making the rounds on the international travel circuit, meeting heads of state. He began in South America and ended up in Washington, D.C. on one of the worst of all possible days to meet with President Bush—right after the November 7 elections.

Despite rifts within his own party and indications that he had lost popular support, López Obrador continued to insist that Calderón would not be allowed to take office. On November 28, amid rumors that the PRD was about to make its move on the congressional podium, the PAN seized the upper tier, sparking a free-for-all and a three-night sleepover as opposing congressional delegations vowed to maintain their battle positions in the halls of Congress. “Pajama Party in the Congress!” barked the headlines of several Mexico City newspapers, whose columnists wondered whether the ever-shrinking delegation of international guests would ever witness Felipe Calderón putting on the presidential sash.

In the end, the backdoor maneuver, which was not shown on Mexican television, accomplished its mission. However improvised, however hastily, Calderón was now the man wearing the sash with the red, green and white colors of the Mexican flag.

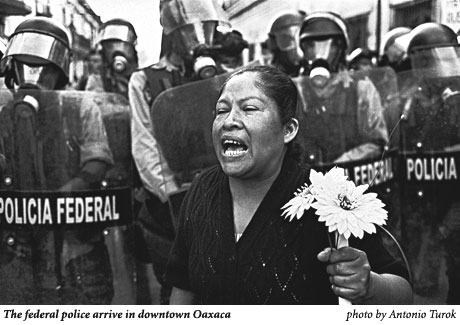

As the sash was passed in Mexico City, the “problem” in Oaxaca raged out of control. U.S. journalist Brad Will, a videographer with indymedia (www.indymedia.org) was shot and killed on October 27 while filming a police shootout at barricades several miles outside of Oaxaca. Fox ordered some 4,000 federal military police into the city. Two days later, the president boomed that peace and tranquility had been restored to the southern state. But the APPO regrouped, and the protests continued. On November 25, a march was called to demand Ruiz’s resignation.

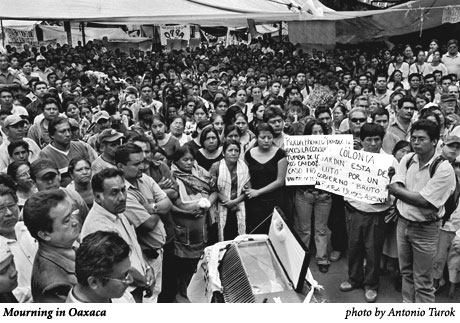

The protest, which started out peacefully, suddenly went very wrong as stones and Molotov cocktails flew and rockets were launched, setting buildings on fire throughout the center. At no time did firemen ever enter the city. When the fires burned down, the courthouse was in ruins; thousands of files were lost. Provocateurs? Infiltrators? Alienated kids? Paramilitary sharpshooters? The immediate response was a roundup of more than 140 people who were sent to prisons far away in Nayarit, in western Mexico, and Matamoros, across the border from Brownsville.

Just days after Calderón was inaugurated, Omar Pérez received an e-mail from the organization he had worked with in the isthmus. Things were very bad—house-to-house searches and illegal detentions; teachers who had only recently gone back to the classroom being whisked out of schools and taken prisoner. Emiliana Cruz was worried about some of her closest friends. She hadn’t heard from her friend Dionisio Martínez since August. Martínez was a leader in the teacher’s movement who had lost a brother in Mexico’s counterinsurgent war in the 1970s.

“He was also an artist, a writer,” says Cruz. “Somebody they would want.” Now she heard that another friend, Gerardo Bonilla, was reportedly missing. Bonilla was an artist who had exhibited in Brooklyn and Barcelona, Chicago and California. Three years ago, he was one of a group of Oaxacan artists whose work was exhibited at Austin’s La Peña Gallery.

On December 4, negotiations were set to begin between the new minister of the interior and the APPO. Instead, soon after giving a press conference in Mexico City, Flavio Sosa, the burly, 41-year-old man frequently i

entified in the press as an APPO leader, was arreste

and sent to a maximum security prison. The following day, an editorial in the Noticias recounted the events that had taken place in the waning days of the Fox administration and the beginning of the Calderón administration: “The presence of the federal police force in Oaxaca, supposedly to ‘re-establish law and order,’ has translated into a generalized breakdown of the rule of law in a de facto state of siege—a repressive escalation that forces us to remember the counterinsurgency of the military dictators that occupied this hemisphere in decades past.”

On December 6, Calderón launched his own national tour in a mountainous village in the state of Guerrero bordering Oaxaca, and revealed a program that he said would help the 100 poorest towns in the nation. “Beyond the colors of political parties, there is only one Mexico,” he said.

And in Oaxaca, there were plans for another march on December 10.