Arts in Aggieland

I wanted to put on a festival like those seen all across Europe each summer, when entire villages are turned into a stage, with stilt-walkers and magicians working the crowds, scholars and writers holed up in the mayor’s reception room, and food stalls filling the streets. Musicians stroll, storytellers perch on the edge of a village fountain talking to a crowd of eager kids. Alleys are lined with kiosks and tents full of craftwork, pottery, beads, and dolls.

This is what I imagined bringing to the dour campus of Texas A&M.

Late in the fall of 2005, I put out a notice to interested faculty and students of plans for something never before done at A&M—a festival to celebrate the art and writing of the Southwest. I have been here for the past 32 years teaching creative writing, watching A&M play catch-up with other universities in the state that have launched bigger and better-funded writing programs. Ours is small but growing as part of a national trend. But we hadn’t made our mark in any public way, aside from the occasional poet or novelist visiting for a day or two.

When I told a meeting of planners what I envisioned, the feeling in the room was, so how do we pull this off? What will the theme be? That was easy—turn all the regional stereotypes inside out, find the writers writing the real thing, not falling back on coming-of-age stories or the poetry of the isolated soul’s finding the whole world hostile to one’s visions. We really wanted to get past the nostalgia for the open plains, grandpa’s ranch, the last Indian weeping under a mesquite bush, the last wild buffalo roaming the desolate hills. Enough already. The Southwest is not just the tomb of the gallant Anglo settler; it’s alive and thriving under an emerging Latino majority, and the growing voices of African-American poets and Asian voices along the coast. And pushing the Southwest out of its macho chrysalis are women re-examining their past with fresh eyes, looking at the looted landscape and the pillaged environment, and demanding change. We wanted to hear about a new, saner, more generous vision of our lives, what to do to help this region rebound and thrive again as a habitat for wild animals and plants, alongside a more tolerant and open-minded humanity.

The event was planned for October, and money trickled in from deans and department heads, the A&M Arts Council, and Bryan’s Arts & Cultural Association. We began signing up headliners like poets Linda Hogan and Lorna Dee Cervantes; Uruguayan poets Ida Vitale and Enrique Fierro, both living in Austin; and wilderness writer Doug Peacock, an old friend of Edward Abbey. Other stars included Steve Harrigan, reading from his new novel Challenger Park, the Hopi poet, and Kachina doll maker Ramson Lomatewama. Novelist and translator C.M. Mayo came from New York on her way to the Texas Book Festival held two days later.

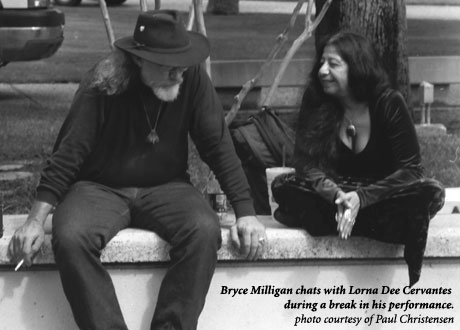

We also brought in the Austin poets Joe Hoppe, Lyman Grant, and John Herndon; and flew in Miguel Angel Zapata from Hofstra University. Bryce Milligan and Roberto Bonazzi drove over from San Antonio; Clay Reynolds, the novelist, drove down from Dallas. Naomi Nye was busy and couldn’t come; others turned us down politely, not quite knowing what to make of our sudden eagerness to open our doors.

There were some anomalies to the mix, like the poet Nathaniel Tarn, an English-born anthropologist who lives in Santa Fe, and Loren Goodman, a poet from Tyler who won the Yale Younger Poetry award last year. We drew on our own faculty, including Larry Heinemann, whose novel Paco’s Story beat out Toni Morrison’s Beloved for the National Book Award, and Angie Cruz, author of Let It Rain Coffee. Poets Janet McCann and Michael Collins read alongside our graduate-student writers Mick White, a Dobie-Paisano fellow, and Jeff Stumpo. We included rock bands, among them Wish Found Nation, Trellis The Valentines, Still Life, and The Favorites. We put folk singers out on the campus, and a storyteller. A high school folk-dance instructor brought his troupe to the Palace Theater. Rain washed out some acts. We had a wide assortment of other heavies and dabblers, and a variety of student poets from across Texas and neighboring states.

In all, we brought together 120 performers and squeezed them into a three-day schedule between October 24 and 26 with events that overlapped and sent people scurrying around the campus. Opening the festival was Karan Watson, our dean of faculties and an electrical engineering professor with Cherokee in her blood. The other festival was about to happen in Austin, the Texas Book Festival, and a score of us were headed there as soon as we brought down our own tent. Maybe that’s why we could reel in some of the bigger stars. And in every case but one, events were well attended, with students filling up most of the rows, taking notes for reports that would earn them extra credit.

The festival was like water spilled in the desert, a sudden greening of A&M in the middle of fall. More than one student told us that “it felt like Austin,” high praise.

The kiosks and stilt walkers were not to be. Permits are required for almost anything one puts on in the Rudder Plaza, the hub of the campus. Our musicians had two hours starting at noon each day in which to sing with a microphone. After that, the plug was pulled, and you went acoustic if you wanted to keep singing. Many did. Getting the Texas Ladies Aside, a Peruvian horse drill team from nearby Caldwell, onto campus required a police escort, a permit to park the trailers, a strict path to the drill field where 50 people stood in the wind as these elegant women dressed like 19th century peeresses rode side-saddle in close-order drill on the patchy grass.

Each night a headliner filled the great hall of Stark Gallery. On the second night, Ida Vitale read her poems and stood aside as the translator recited English versions. At one point the back door flew open, and a stout dancer dressed in feathered headdress and bells came up the aisle, only to be chased off by the poet Eduardo Espina, host of the reading. The dancer, a huge, 6-foot-5 brave, was part of the Alabama-Coushatta tribe, whom we had hired to dance outside. But rain forced them indoors into the cavernous Flag Room, a hall full of sofas and huge marble globes studded with flags. Students piled in to watch the rain dance, the slow, mincing steps of a harvest dance, the gentle, bell-jingling shuffle of the women, and finally a round dance that we all joined.

In the afternoons, beards and ponytails mingled with cadet uniforms and sorority girls. A folk singer slouched in the corner of the plaza and twanged away, with a few onlookers stopping to tilt a head and wonder what it was all about. Boots were everywhere— Don Graham’s worn-out boots; Mark Busby’s ropers and blue jeans; Seth Prichard, the story teller, had on full-quill ostrich specials. The rest of us were in sneakers or sandals. Susan Bright’s long, ashy hair cascaded down her shoulders and over her cloth book bag as she held court. Her hand was up much of the time to quibble over facts or to fill gaps at the “Black Southwest” panel. Students eyed her curiously; debate is rare in classes here. Suddenly everyone had a point to make, and the students began to relax, to open up. Why not?

The festival came on the eve of the elections and the turnover of Congress to the Democrats. Robert Gates, our outgoing president, had rammed through some far-reaching reforms that had made A&M more attractive. Not only had he hired 400 new faculty, the student body now has far more African-American and Latino students than at any time in its history. Morale was up, and Gates was just big enough to talk back to conservatives and boosters of Ole Sarge and the Aggieland of the past. He could move the rock a good way to the center, but he couldn’t reach down to the middle managers as fast as he wanted. Now he was leaving for the Pentagon to clean up after Rumsfeld, but leaving behind a work in progress. That, too, had its effect on how we felt. There was something crisp and clean in the air those three days, with kids beaming and running off to hear more writers. After Linda Hogan finished reading, a line of young women holding newly bought copies of The Woman Who Watches over the World formed. She spent time with each, and their faces told you everything. Others waited to talk to Doug Peacock at the Wednesday night reception, and students formed a circle around him.

When it was over, we hadn’t quite transformed the trim lawns and stately oaks into a carnival ground, but we had succeeded in launching a very public affair that spilled over from the campus into College Station and Bryan. We used bars and amphitheaters to accommodate the bands, and the little Revolution Café was jammed with students listening to Paul Ruffin’s stories. Sitting back in the corner of the bar, peering through chinks in the crowd, I had to admit—it was like Austin. It could have been the Cactus Café or the Broken Spoke on a regular night. It could have been away, but it wasn’t—it was right here in Aggieland, and we will do it again.

Paul Christensen is a poet and essayist who teaches modern literature and creative writing at Texas A&M. His new book of poems, Hard Country, won this year’s “Violet Crown” award for best book of poems awarded by the Writers’ League of Texas.