Better Debate Than Never

Where’s the governor?”

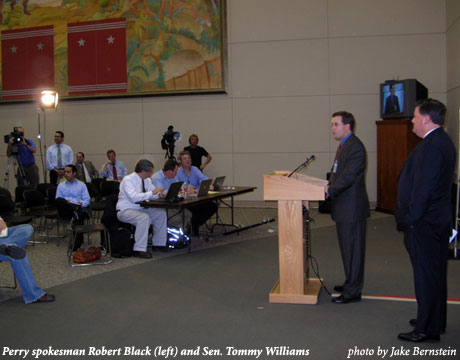

The lone debate of our bizarre four-person race for the Texas governorship had been over for barely 20 minutes on October 6, and already incumbent Rick Perry had apparently fled the scene. Perry, like his three opponents, was scheduled to meet with the press following the hour-long debate. He was the only no-show. That left the assembled reporters—sequestered in the high-ceilinged, glass-encased lobby of a gated-studio building in Dallas—with one question on their minds. They kept shouting it at Perry campaign spokesman Robert Black, who manned a position behind the podium in place of his boss.

“Where’s Gov. Perry?”

Black tried to ignore it. “Gov. Perry won the debate decisively tonight,” he began.

“Where’s Gov. Perry? Where’s Gov. Perry?”

The reporters hurled the questions at him like rocks. Black, perhaps sensing the makings of a mob, finally responded. “The governor’s not coming,” he said. “The governor said what he had to say during the debate.” That non-answer answer only stoked reporters’ ire. Black plowed ahead: “I’d like to introduce state Sen. Tommy Williams, who will speak on the governor’s behalf.” Williams, a rotund Republican from The Woodlands, stepped to the podium. He looked like he’d rather be having gum surgery.

“Where’s Gov. Perry?”

Williams began his statement: Perry won the debate and is the only candidate with a vision and a plan for Texas. Most reporters didn’t even bother to write it down.

“Where’s Gov. Perry?”

Williams finished quickly, and Black, a tight little grin fixed on his face, returned to the microphone.

“Where’s Gov. Perry?”

“He’s on his way back home,” Black said.

“Is the governor afraid to talk to the press?”

At this, Black stopped grinning and narrowed his eyes at the questioner. “No, the governor’s not afraid to talk to the press.” He said the governor meets with reporters all the time—in Austin and on campaign swings all over the state. This was news to most Capitol reporters. “He’ll be in a debate. He will be debating for the next 30 days with the people of Texas.” With that, Black walked out while aides distributed a press release from the Perry camp. It was a two-paragraph statement, not from Perry, but rather from Black, providing further description of Perry’s “decisive victory.” Reporters shook their heads. A consultant with the Kinky Friedman campaign standing nearby observed, “I guess that’s why 65 percent don’t like him.”

There’s a fine art to winning re-election when at least 60 percent of the electorate plans to vote against you. It helps enormously, of course, to have the anti-Perry vote spread among Democrat Chris Bell and independents Carole Keeton Strayhorn and Kinky Friedman. Perry’s base will likely deliver him no less than 35 percent on November 7. That gives the incumbent about a 10-point lead with a month to go, according to most polls. To win, Perry simply needs to run out the clock.

The entire night’s events seemed designed to shield the governor from as much public exposure as possible. That was the political strategy behind ducking the statewide media—sidestep a chance to put his boot in his mouth. Similar political thinking guided Perry’s rejection of at least five other invitations to debate his opponents. The one debate he did agree to was scheduled on a Friday night during high school football season and the night before the University of Texas-Oklahoma showdown across town in the Cotton Bowl. The four candidates debated in a closed-off studio without an audience. In fact, the only members of the public or press who actually saw the governor in the flesh were the four reporters asking and moderating the questions. To make matters worse, the company that hosted the debate, Belo Corp.—the Dallas-based owner of the Dallas Morning News and numerous television stations—decided to treat the broadcast rights like Coke handles its secret recipe.

As debate sponsor, Belo could set the broadcast rules, and company executives refused to allow any but their own stations to show the debate live in Houston, Dallas, Austin, and San Antonio. They did permit PBS and Spanish-language stations in those markets to air the debate, but only on tape delay, and only for four days afterward. “We’re not going to go through all this time and expense to hand over our work and investment to competitors in the marketplace,” WFAA station manager Mike Devlin told the Austin American-Statesman. So much for the idea that the right to access the public airwaves brings with it responsibilities to the public.

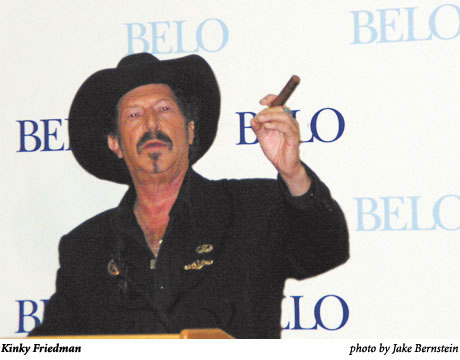

Despite the odds, the debate drew surprisingly good ratings. It was the most-watched show in its time slot on Friday night in every major market except Dallas-Fort Worth, where it finished third. Those who did tune in saw a motley crew of candidates: the governor, hair resplendent as ever, laboring to defend a lackluster record in office; Friedman, dressed in his black “preaching coat” and cowboy hat, waving an unlit cigar but landing few of his famous one-liners in this unfamiliar format; Strayhorn, the fast-talking Democrat-cum-Republican-cum-independent state comptroller, standing out in an electric pink jacket; and Bell, the earnest Democrat, who looked like an eager-to-please tax lawyer.

Yet it was Bell who fired off the night’s first zinger. Following bland opening answers from his three opponents to a bizarre immigration question (it’s a federal, not a state matter), Bell offered, “I’m glad to have the opportunity tonight to stand here as the Democratic nominee with my three Republican opponents.” He then called for more sensible immigration policies, asking, “Does anyone seriously believe that we can deport 12 million people?” A few minutes later, the candidates got to ask each other one question. Bell was assigned Strayhorn, and the Democrat hammered her for accepting campaign contributions from tax firms that do business with the comptroller’s office. Strayhorn denied the charges, but Bell wouldn’t let her off the hook in his rebuttal. “The facts are the facts,” he said. “It’s part of the pay-to-play culture that currently exists in Austin.”

Strayhorn had the good fortune of winning the right to ask Perry a question. There’s no shortage of fodder, and political geeks had speculated for weeks how vicious Strayhorn might be. But when the moment arrived, Strayhorn ventured way out into right field, asking why Perry hadn’t passed a “Jessica’s Law” to increase punishment for pedophiles. It was an odd choice. Jessica’s Law hasn’t been a major issue in the Legislature, nor on the campaign trail, and Strayhorn herself has rarely mentioned it. The question seemed a transparent and clumsy stab at taking advantage of the recent scandal surrounding former Congressman Mark Foley’s advances toward underage congressional pages. Perry, looking relieved, easily brushed aside the query: “I’ll tell you what, one thing people don’t get confused about is that Texas is a tough on crime state.” He noted that first-time sex offenders receive an average of 20 years in prison, and then floated the idea that repeat offenders should get the death penalty.

Strayhorn had a tough night all around. She talked at a sprinter’s pace, racing through stump speech lines such as, “In a Strayhorn administration, we’re going to shake Austin up and tell people the truth. We’ll put the people first, not the special interests.” Despite the breakneck speed of her patter, she was cut off midsentence at least four times when her responses ran too long. Several times, she mentioned something called the Texas First Plan and something else called her Texas Next Step Program, but she never quite had time to describe what they are. And, of course, Strayhorn provided the night’s headline moment when, during the highly entertaining lighting round of political Jeopardy in which candidates had 15 seconds to answer rapid-fire questions, she couldn’t name the president-elect of Mexico, Felipe Calderón.

Bell was the sharpest of the four. He was asked a trick question in the lightning round, “What’s the term limit for Texas governor,” and the Democrat produced the line of the night: “There is no term limit for Texas governor, and that’s why people should be horrified—because Rick Perry says he plans to run for another term if he’s successful this time. That’s the best reason I can give you tonight to vote for me.”

Perry tried to remain above the fray and emerged relatively unscathed. The governor fiercely defended his most controversial policies, especially the Trans-Texas Corridor plan. Perry’s lone moment of unease came, oddly, during his closing statement, which he appeared to read from notes. He twice lost his place and fumbled sentences. It’s also worth noting that Perry’s closing statement contained his only obvious attack of the night, and he aimed it, interestingly enough, at Bell—accusing the Democrat of supporting big government. That may indicate that Perry’s camp considers Bell the one remote threat to the governor’s re-election. It also served to further minimize Strayhorn.

The post-debate news conferences offered revealing contrasts of styles. Bell was the first to venture into the lobby to meet with the press in front of a backdrop with “Belo” scrawled all over it—lest we forget who was bringing us our public debate. Standing with his wife, Alison, Bell announced he would receive significant new financial support from wealthy trial lawyer John O’Quinn. The attorney who helped win the state’s tobacco lawsuit later said he would pledge $1 million to Bell and raise another $4 million. “He’s not going to lose for lack of money,” O’Quinn promised reporters.

Kinky was next, and the musician-author paced behind the podium while firing off one-liners he probably should have used in the debate (“Rick Perry is the well-lubricated head of a well-oiled political machine. He says nothing and does nothing”). Kinky was hammered in the debate for past racist comments that have emerged during the campaign. Yet he was never humiliated on a detailed point of public policy, of which he admittedly knows little. Asked to assess his performance, the Kinkster declared, “I’m still voting for myself.”

Strayhorn appeared with each arm draped over a granddaughter and two of her sons, Brad and Scott McClellan, standing behind her. (Scott, you’ll recall, is a former White House spokesman.) Given her dismal debate performance, the scene had the feel of a farewell tour. It’s worth remembering, though, that the self-proclaimed One Tough Grandma still has more than $5 million in campaign cash to spend.

And then there was Perry. Or, more accurately, there were Perry’s surrogates, who confidently declared victory to the media and walked out.

The debate seemed unlikely to dramatically alter the race’s dynamic. Perhaps the night’s most striking aspect was how much the whole episode seemed emblematic of the current political moment in Texas. Consider the recent controversies: The state plans to grab farm land using eminent domain for a megahighway for which the contract—recently signed with a Spanish company—still hasn’t been made fully public; power companies try to build 17 new coal-fired power plants, though Texas already leads the nation in mercury pollution; and the Texas Ethics Commission considers a rule that would allow public officials to receive cash “gifts” without having to disclose the amount. The small cadre of rich men running the state has rarely seemed more powerful or secretive.

So it seemed appropriate that the most public of political events—a candidates’ debate—took place in a studio deep inside a media corporation’s sprawling complex, walled off from the public and the press (save for the three reporters asking questions), while everyone else watched on television. And when it was over, the state’s highest public official bolted out the back door under the cover of darkness.

Additional writing and reporting contributed by Jake Bernstein.