For Texas and Chile, an Axis of Anti-Poetry

Forty-one years ago, in July 1965, I made my first trip to Chile, as part of an exchange program suggested by Vice President Richard Nixon after his car was stoned in Venezuela in 1958. This State Department-sponsored program matched universities in South America with U.S. universities to create good will and better mutual understanding. But after a couple of years, only the exchange between the University of Chile and the University of Texas at Austin continued, lasting from 1959 to 1968.

Before leaving on what would prove a life-changing adventure, I flew with our group of 15 students to Washington, D.C., to be briefed on political issues, perhaps the hottest among them being the recent U.S. invasion of the Dominican Republic. Most of our group was made up of “student leaders,” like Kaye Northcott, editor of The Daily Texan [later editor of the Observer], and Ricardo Romo, the University of Texas track star who is now President of UT-San Antonio. In previous years, Carole “Grandma” Keeton Strayhorn and Lloyd Doggett had participated in this same exchange program. I had been the editor of Riata, the UT student literary magazine, and was probably chosen partly because a few years earlier Oscar Hahn, now considered one of Chile’s leading poets, had come to Texas in the program. My role was basically to demonstrate that Texans, too, were “into” poetry, including the poetry of Chile.

Little did I suspect that four decades later I would not only still be “into” Chilean poetry, but that I would be taking a group of UT students to study Chile’s grand tradition of world-class poets in situ. But thanks to the three-year-old “Maymester” program, in which students from UT-Austin travel abroad with a UT professor, I was able to help another group of Texas students come to know this long, thin land, to read its epic poets—including two Nobel Prize winners, Gabriela Mistral and Pablo Neruda—and actually to meet the revolutionary Nicanor Parra, former physics professor and winner of international renown for his “anti-poetry,” published in translation in New York by New Directions Press.

After my first trip to Chile, I returned the following year and formed a deep and abiding relationship with the country when I married my Chilean wife, María. Over the years we have returned to Chile numerous times, and I met with Parra several times. It was my special wish that the students who accompanied me to Chile on my most recent trip would have the unique experience of visiting the anti-poet, who on September 5 turned 92. Happily, they were able to visit Parra’s home on the Pacific Coast, listening to him as he recited from memory a Mexican border corrido and as he spoke of his great love of Shakespeare, whose King Lear he has translated into Chilean Spanish.

While we were reading Chile’s poets, the country’s secondary students were engaged in a nationwide protest over the conditions under which they are being educated. Paralyzing parts of the capital, Santiago, students marched with banners proclaiming their discontent with everything from bus fares needed to navigate the far-flung city, which exceeds New York City in area, to the inequality among schools that do not receive the same level of funding—reminiscent of our own Robin Hood controversy. Some of our group found the protest the most exciting part of the trip, though they soon decided that it wasn’t so safe to be in the line of fire of the so-called guanacos, water-spouting police vehicles named for the Chilean animal that spits at its opponent. It was clear to our group that Chile’s form of democracy allows for such protests, in which students take over a school and close it, under the protection of Chilean law. University students also shut down their campuses in symbolic solidarity with their high school fellows, which meant we were unable to visit classes at the Universidad Metropolitana.

We did, however, meet with a group of Chilean students from the Universidad de Desarrollo who were intrigued by the fact that we were studying their national poets. They felt that their own countrymen did not recognize fully the value of their own literature. This, I pointed out, is perhaps the case universally, even though it does seem that Chileans are quite aware of their country’s impressive poetry tradition—even taxi drivers know who Parra is. It is perhaps ironic that Chile has produced so many fine poets with international reputations by denigrating the traditional view of poetry as beautiful, if useless, language. As Parra has written, “poetry for the older generation was a luxury, for us it’s an absolute necessity,” even if he terms it “anti-poetry.”

After two weeks in Santiago, we moved our base of operations to the coastal community of Reñaca, a popular beach area during the summer season, but pleasantly relaxed in late fall. Nearby, our classes were held at the Universidad Marítima, where professor German Vogel and a number of his law students welcomed us warmly. As they listened to the sound of crashing waves, the students worked on their poetry papers and began to look forward to their visit with Parra. As many Chileans told them, they were in for a special treat. (Two teachers, who gave my students classes in Chilean slang, told them that they were envious and wished they could come along and meet the famous anti-poet.) Before the visit, we read some of his typical poems, like one that says “Let the poets come down from Olympus,” meaning that they need to deal with the real world. Parra is concerned about ecological destruction, and has declared, in the voice of God, “If you destroy the Earth, don’t think I’ll create it again.”

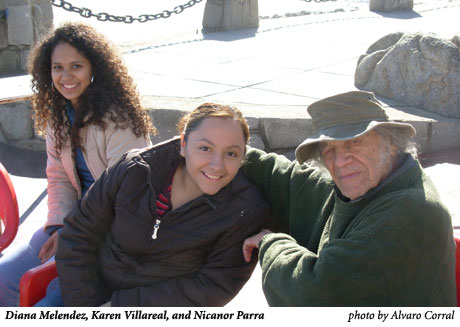

At nine in the morning on June 9, we and our wonderful guide, Paula Olguín, departed in a van for Las Cruces, a small fishing village located next to a spectacular bay. To escape the polluted capital, that’s where Parra lives. After we arrived, the anti-poet took us to a grassy area on the side of his house and began to talk about The Taming of the Shrew, comparing it with a work by a Spanish writer of the 15th century. From time to time, with gusto, he would quote Shakespeare in English, but when he noted that all but one of the students were Mexican-American, he launched into a long corrido about a Mexican who crosses the border and finds a tragic end. The students were duly impressed; one, Karen Villarreal, told Parra it was her father’s favorite song. Parra then commented on the current Chilean students’ protest movement, suggesting that the name “penguins”—as the students were referred to in Chilean newspapers—probably came from the fact that this bird with wings too short for flying has to claw its way along to get where it wants to go. He then invited us to walk along the beach. The students were hardly able to keep up with this 91-year-old anti-poet, who, they noted, had nothing about him that suggested his age, no wrinkles, no stooped back. He declared his secret was to take megadoses of vitamin C. His fisherman’s hat, sweater, baggy pants, and lace-up boots were, as he has revealed, all secondhand, even though he has won nearly a million dollars in literary prizes. As Parra explained, his only interest is his writing and the artifacts that he creates, including the white plaster statue in his house of a Greek goddess with his ironic sign that reads: “I’m frigid. I’m only moved by profit-making.”

Parra is famous for his dislike of cameras, but he allowed himself to be photographed with several students. For me the visit with the anti-poet was the highlight of our trip. It was a dream come true to share with another generation of Texas students the land of the highest mountain range in the Americas and of the grandest tradition of poetry in Latin America, with Parra for my money the most original and brilliant poet in the 21st century.

Dave Oliphant’s latest book, Jazz Mavericks of the Lone Star State, will be published by the University of Texas Press in 2007.