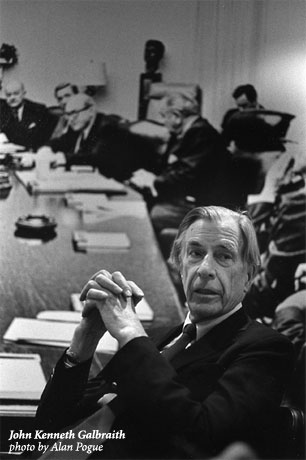

Ken Galbraith is Gone

Remembering the giant who did so much in the endless struggle for justice

Ken Galbraith is gone. The tallest and grandest tree in the Harvard neighborhood fell on April 29, from complications of pneumonia, at 97.

What a life he led. In his 70 million copies of his four dozen books distributed around the world, the six-foot eight Canadian did more than any economist to insist and teach that in democracies economic arrangements are determined by political power, making social justice the proper focus of economics. As his biographer Richard Parker says, Galbraith was a liberal who believed in markets offset by both government regulation and the welfare state. Initially his underlying theory of societal shape was countervailing power; economics, he saw as a balancing of power between giant corporations and powerful labor unions. He lived to regard as misbegotten even that modified faith in markets—that is, in capitalism—as the major corporations successfully conspired with the government they have literally bought to ruin the union movement and obscenely begin to reverse, step by step, the welfare state.

In the fall of 1973, in his book Economics and the Public Purpose, (in describing which I am following Parker’s biography), Galbraith shocked the conventional wisdom with what in a different history could have become the second New Deal, carrying forward the spirit and thought of the 30 “Young Turks” in the U.S. House in the 1930s, who were led by Maury Maverick of San Antonio. Galbraith advocated five kinds of limited socialism that variously were (and are) already safely and beneficially in use in Western Europe and Japan: “public service socialism,” direct public authority over health care, transportation, and housing; “defense socialism,” making military contractors publicly-owned enterprises to curb wasteful weapons systems and military adventurism; “technostructure socialism” to correct the impotence of stockholders at controlling the corporations they “own,” buying out (at full value with Treasury bonds) the stockholders of the largest several hundred corporate giants and bringing them under public ownership; “the socialism of ends,” direct public planning of goals and ends and of productive output; and “socialism in support of the market,” the government providing “research and technical support, capital, and qualified talent” for small business while stabilizing prices and profits. Galbraith made dozens more proposals including an expanded and increased minimum wage, a guaranteed annual income for the poor, and greater government support for unionization.

Though he was 1,700 miles away from Texas, Galbraith was a force in Texas liberalism and with The Texas Observer from the first. I recall receiving a note on his half-sheet stationery from the Littauer Center at Harvard just as we started out on the Observer, enclosing $100, I believe it was, making him a lifetime subscriber, and throughout the decades we received notes of advice and contributions from him.

He was as essentially a politician as he was a professor. One reason I was enthusiastic about Adlai Stevenson for President in the 1950s was the wry and self-mocking, always original jokes with which he opened his speeches. Many decades later my regard for Adlai suffered when I learned that Galbraith wrote those jokes. Galbraith, entering fully into the Observer’s suspicion and distaste for the presidential candidacy of Lyndon Johnson, became a key adviser to John Kennedy, opposing Walter Heller’s tax cuts in the name of Keynesianism and as early as 1961 starting a series of messages to Kennedy warning him not to wage the war in Vietnam. As Kennedy’s ambassador to India Galbraith significantly moderated the war then between China and India. Galbraith wrote Johnson’s speech starting off the Great Society, but turned down other job offers from Johnson because of Vietnam.

Galbraith was a very funny man. He told Kennedy he wrote him directly from India because corresponding with the State Department was like fornicating through a mattress.

Receiving one of his many honorary degrees, he said that his only rule about them was to get more of them than Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. As for the supply-siders’ trickle-down theory of prosperity, he said that, “After feeding oats to the horses, one should not gaze too closely at what trickles down to the sparrows.”

Those who knew him intimately said Ken was not given to anger, yet I believe I angered him one night, during dinner at the home of Richard Parker, by expressing my view then that Ralph Yarborough, the leader of the Texas liberal movement from the late fifties through the sixties, should not have become a candidate for President. Galbraith was a loyal Democrat through to the end of his life, bridling against too much disappointment with leading Democrats, with the exception of Lyndon Johnson in Johnson’s Darth Vader incarnations. When he was angry Galbraith turned cold. His reputation for arrogance may have been caused by his coldness when he was angry.

On the night of the 1970 election, when it had become clear that Lloyd Bentsen had defeated Yarborough in the Democratic primary for U.S. senator, Ralph called me into his office, and for more than an hour made the case that, in defiance of his defeat, he should now become a candidate for the Presidency in 1972. Because Ralph’s desk was always piled high with unfinished tasks, because he did communicate with enough of his constituents, and because he blamed his best supporters for his defeats—because, in private, he was often furious and excitable—I thought him not a good enough candidate for President. During that long session I made notes assiduously, neither agreeing nor disagreeing, which in the personal context meant I disagreed. It was years later, during dinner at Parker’s, that my telling this to Galbraith angered him.

Since then I have thought quite a lot about that night in Ralph’s office and about the history of the country since 1970. I now believe Ralph Yarborough was right, that this great populist Southern senator should have run for President in 1972. Take from this, if you will, a lesson for the future. When deciding about those who have earned the public’s trust as reliable friends of the people, set aside their personal failings, their comings-short of being wholly wise and equable, and consider first the needs of the people and the condition of the body politic.

Although I think Galbraith never forgot that night at Richard Parker’s, he held no grudges. Amicably we shared a few times a park bench in the Francis-and-Irving-Streets neighborhood just off-campus at Harvard, near where my wife and I also live now with our English cocker, Nicky. When I was taking my four years out from the Democrats, experimenting with support for Ralph Nader for President, I called on Galbraith at home and asked him to join with us. Gently, indeed, apologetically, he said he understood, but explained that he had always been a Democrat and he would not be changing at his age. The last time I saw him, Jim Hightower and I called on him in his upstairs study, exchanging our views on the times, with Ken partially reclined on a chaise lounge, on which, apparently, he was most comfortable.

In his last note with his contribution to The Nation he said: “Continue. Do not relent.” According to The Nation, at the end he told his doctor, “I’ve had enough now.”

God knows John Kenneth Galbraith did his part in the endless struggle for justice.

Ronnie Dugger is the founding editor of the Observer.

Sidenote

Dear Co-Editors,

For the last 25 years, or in any case a considerable part of it, my interest in Texas politics has been minimal and my knowledge of it greater than that of any other state, possibly even including Massachusetts. The reason for this remarkable asymmetry is The Texas Observer. The writing is so good, the liberalism so good, and the humor so sharp that I am forced to learn about things in Duval County completely against my instincts and will. I intend to continue my reading of the Observer either in this world or, subject to whatever inconvenience, from the next for all of the ensuing quarter century.

Yours faithfully,

JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH,

Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

This note to co-editors Kaye Northcott and Molly Ivins, published in the December 28, 1979, issue of the Observer, is one of the many that John Kenneth Galbraith sent over the years. We wish him continued happy reading …