The Face Maker

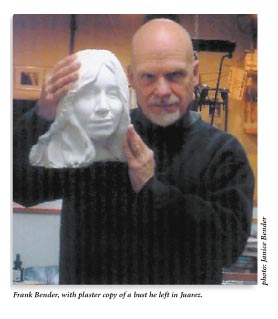

Combining science, art, and intention, Frank Bender tries to restore identity in Juarez

Frank Bender is an East Coast native who knows maybe four words of Spanish and not much more about countries where Spanish is spoken. Lately, though, he’s become obsessed with Ciudad Juarez: with bringing the women murdered there back from the dead—or at least, back to a semblance of life that might solve a decade-long spate of murders in Mexico’s biggest border city.

Juarez has been littered the last 10 years with scores of unidentified female corpses. They are part of a bigger body count: almost 350 girls and women killed variously by husbands, boyfriends, uncles, sons, neighbors, and, apparently, also by strangers. The corpses frequently retain signs of stabbing or shooting or strangulation. Many have been raped and mutilated.

The violence is appalling, but as any police detective will tell you, the first requirement for solving a homicide is the victim’s name. When a dead body is so rotted that identity is gone, the murderer will usually walk free.

Frank Bender restores identity.

If you visit his cluttered, combination home and art studio near downtown Philadelphia, he will lead you to long shelves of plaster busts. One is of a teenaged black girl with eyes that gaze heavenward, like a saint’s. “Her corpse was found in back of a high school,†Bender explains. He points out a young white woman with long, brown hair and a fatalistic, half smile, half frown. “This is Yvonne. She liked guys who were sharp dressers. Got mixed up with her boyfriend in a drug deal that went bad. She was killed in New Jersey then dumped in a woods near Philly.â€

The police at first knew nothing about gazes and dandies and drugs, because they had no idea who these dead people were. That’s where Bender comes in. The cops give him a skull. Sometimes it’s bone-dry and bone-clean. Other times it’s confounded with rotten tissue, and he gets paid extra to stick it in a pot of boiling water until the detritis falls away. Then the skull is tabula rasa and Bender makes a cast of it. After that he starts mapping the vanished identity by mounting little tubes of varying lengths on certain landmarks, like the cheek prominences and forehead. The tubes look like cut-up cigarettes and rise like girders in a tiny, Barbie-doll construction project. Bender lobs clay on the tubes and smoothes until they disappear. He gives, takes away, carves, and smoothes some more. A face takes shape. When it’s finished he casts it in plaster and shaves the mold line. He paints over the chalky whiteness: just the right skin tone, the correct shade of hair.

Skulls don’t show color, of course, and Bender can only guess at it, just as he can only take a stab at curly or straight hair, styled or indifferent, short versus long. But the choices he makes come from deduction and sixth sense.

Take the case of the girl found by the high school. A photograph of Bender’s sculpture of the corpse was widely distributed, leading to the identification of the young woman. After seeing Bender’s work, her parents supplied a photograph of their daughter that’s a dead ringer for the sculpture—right upturned gaze, in both the picture and the plaster. “Her parents were amazed that I knew she did that with her eyes,†Bender says. “How did you know?†I ask. He explains that sometimes police show him photographs of clothing found on the body. “Her clothing was so conservative that I guessed she didn’t pay much attention to people around her. I thought her eyes would also show that.â€

The girl’s race was easier: Bender—who has combined art training with a study of forensic anthropology—says you see ethnicity in certain bony features of the skull. But nuance of skin tone can be a mystery. On the shelf is a bust of another black girl, whose face Bender painted reddish brown. Police used the bust to establish an identity, and indeed, Bender says, the victim did turn out to have coppery skin. “How could you have known that?†I ask. “I dreamed it,†he shrugs.

Karen T. Taylor is an Austin-based, freelance forensic artist and author of Forensic Art and Illustration, the only textbook in the field. Taylor, who teaches facial reconstruction at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia, says she respects Bender’s ability so much that, “I mentioned Frank in my book. Not only does he consistently use wonderful art skills in his work, but he also incorporates reliable insights. He has broken ground by employing sculpture for facial reconstruction, rather than photography or drawing. He’s an innovator.â€

Bender’s combination of science and almost preternatural intuition first emerged back in the 1970s, shortly after he left the military and finished a few years of night courses at an art school in Philadelphia. A friend who fingerprinted bodies in the city morgue took him for a visit; they passed an unidentified, decomposed corpse and Bender said, “I can tell what she looks like!†The medical examiner overheard and challenged Bender to reconstruct the face. “That was the first sculpture I ever did,†he recalls. Today he is one of a few artists in the country who work with law enforcement to reconstruct identity from bones. In addition to doing forensic work, Bender has earned a living as a boxer, a tugboat worker, and a commercial diver. He has been profiled for an upcoming Esquire article and his life has inspired an HBO documentary that is currently in production.

Bender got involved with the Juarez murders after Robert Ressler, a retired FBI serial-killings expert, did some work for the Mexican police on the cases and recommended that the cops invest in facial reconstruction. Bender first went to Juarez in August of last year, then spent three weeks in October working with five skulls.

He says he started by looking as closely as he could at the city’s female population. After all, their bodies, skin, clothing, and grooming constituted the sociology of the community—the guidebook, as it were, to those whose faces he aimed to recompose.

Of the women of Juarez, Bender says, “I observed them in Sanborn’s. In the hotel lobby. The girl who worked behind the bar. I went to where the border bridges are, the factories, and five minutes from there, the neighborhoods with cardboard houses and dirt roads and no street lights. The only time I ever saw a girl with short hair was on rare occasions downtown. Otherwise, it was long hair, parted in the middle or off center, and maybe pulled up in a bun in back. I didn’t see much makeup except a little eyeliner, and the earrings are just little gold loops. Girls who work in the stores downtown have a more American style: hip huggers with the midriff showing. Farther away, the style was conservative. The police showed me photographs of the clothes found around the bodies. I saw stuff like dresses below the knees. Nothing sexually revealing.â€

At the Hotel Luzerna, near downtown Juarez, Bender was locked in a room with the five skulls and a police guard outside. No one could come in, not even the maids. “I went nowhere; I had my food brought in. I spent all the time with the skulls. It was like living with these women 24/7,†he recalls “I would get up in the morning with them in the sunlight. I saw them at night in the moonlight. Every time I woke up I would give them attention: put more clay on, do some molding.â€

One of the skulls, of a woman who seemed to be in her twenties, made an immediate impression. Bender recounts how, as he proceeded with the reconstruction, “I could see she was attractive but with strong anomalies from one side to the other. Her nasal spine was off to her right, and her teeth were off.†During the final phase, where details emerge more from art than science, “I parted her hair to the side and let it hang over her face. I figured a girl would do it that way to camouflage her asymmetries.â€

“When the police came in and saw what I’d done they were shocked. ‘This looks like the girl we ruled out!’ they said.†The cops had already done DNA tests on the corpse, and on the parents of a missing girl, Bender says, but the results didn’t match. “Now these parents came in and you could clearly see the similarities between the mother and the face I’d just reconstructed. The parents went right up to that one sculpture and kept touching her.â€

Who does Bender think killed this young woman and others like her? “I think it’s perpetrators—and I emphasize plural,†he says. He suspects not one serial killer but a panoply of males who’ve declared “open season on women†because of women’s rapidly changing role in Juarez, from stay-at-home mothers and daughters to students and workers—in a society still rife with machismo. (Bender came to this conclusion based on experiences he had during his short stay: “A woman can’t even live alone in Juarez without being considered a slut, a whore. I became friendly with this one fellow, a divorcee, whose girlfriend was still living with her parents. They were so opposed to her dating a divorced man that he had to sneak to her house and throw stones at her window to get her attention so they could go out. And she was in her thirties!â€)

The gender-role backlash killers, Bender thinks, are mostly unrelated to each other: people in the drug trade, pimps, a few serial sex killers and their media-inspired copycats; as well as some government officials and cops—not an organized network of the last two, but just enough bad apples to impede investigations. (Bender himself was threatened—“I got a call to the hotel saying I should leave Juarez or I would die. The police said it was from a drug cartel.â€)

In general, Bender has great respect for the Juarez cops’ current efforts. The main problem, he says, is that they have so few resources. “The team that is down there right now is really, really trying to solve the crimes. They are totally devoted,†he says. On the other hand, he has seen and heard of astoundingly primitive and ignorant practices during investigations into the women’s murders: crime scenes left open to public, vandalism, evidence thrown out, DNA samples gathered incorrectly and put through outdated tests.

He blames these mistakes on lack of training and lack of professionalism. “The police told me a state policeman makes less money working 24-hour shifts, on call seven days a week, than working at a Burger King in El Paso. I’ve seen them work until two a.m. and get up at six and go out on another job.â€

Nevertheless, Bender says, foreign criminology experts have been consulted, and the Juarez police “have made major strides because of cooperation with the U.S., Spain and France. Those countries have helped build a lab in Chihuahua. I saw it and it’s phenomenal. Some of the technology is even better than in the U.S. But the Mexicans can only train so many technicians. They’re training people as fast as they can but they’re limited by their budget.â€

Bender’s trips to Juarez to reconstruct the five skulls were paid for by the government of the state of Chihuahua. “Now the state says it can’t afford to pay me for more work,†he says. He is irate at recent budget cutting that has decreased the number of cops. “It’s as big an atrocity as the murders,†he says, and wonders why the federal government doesn’t fund the investigation.

These days he’s back in Philly, haunted by the skulls whose faces he rebuilt, but more so by the dozens that are still only bone. “I want to go back and do all of them,†Bender says. “It would take me a year. Even if the state has no money, photos of my reconstructions could be posted for almost nothing at bus stations, by maquiladoras, in places throughout the country where these victims might be recognized.â€

As for the five skulls, they are still ciphers—including the pretty woman with the crooked face. “The police think that the first DNA tests got messed up, and the parents were asked to give new samples. But they refused. I think I understand. Maybe they’re in denial. They kept touching the reconstruction I made: the face, the hair, the off-centeredness. Maybe they feel that after she’s identified, they won’t get to touch any more.â€

Contributing writer Debbie Nathan lives in Manhattan. Her article about Juarez, “Missing the Story,†was published in the August 30, 2002 edition of the Observer.