Hearts and Minds: Cuban Photography

Merrell Publishers

Havana in My Heart: 75 Years of Cuban Photography

125 pages, $29.95.

The genius and the curse of photography is that it captures (or creates) solitary moments, engraving them in tarnished silver or inks and dyes on a sheet of paper. How wonderful to be able to save and savor the graphic and dramatic shades of a single moment. How frustrating not to know what happened a moment ago, what will happen next, or how and why the elements in the picture came together just so.

That feeling of frustration can only be compounded when the subject is as ethereal as the nation, the culture, and the state of mind of Cuba, which has come to carry so much meaning for so many. Two recent collections of Cuban photographs–that is, photographs made by Cubans in Cuba–trace very different routes through contemporary Cuban history and photography.

Gareth Jenkins’ Havana in My Heart is a nostalgic look at the people and places of Havana. Jenkins is a British business consultant specializing in trade in Latin America and Cuba. He has clearly fallen hard for Cuba and wants to share a vision of the city he loves with the world. Toward that end, he has gathered pictures from the Prensa Latina archive, the Cuban National Library, and the files of various Cuban photojournalism magazines.

Shifting Tides: Cuban Photography After the Revolution is the catalog for an exhibition of photographs that editor Tim B. Wride curated at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Wride focuses on the evolution of art photography from the reportage and propaganda of the late 1950s through the surprisingly conceptual, abstract work of the late 1990s.

In the preface to Shifting Tides, filmmaker Wim Wenders writes that although Cuba is geographically in the middle of North and South America, it feels like “a place in the middle of nowhere in terms of both space and time.” When you emerge onto the street from a Cuban cinema, he writes, you blink your eyes and ask where am I? What year are we in?

You can get the same feeling looking at some of the photos in these books. To try to help readers find their way through the pictures, both editors classify the pictures by broad categories. Havana in My Heart has chapters called “Street Scenes,” “Revolution,” “Everyday and Ritual”, and “Artists and Performers.” There are archival shots from the late 19th century and from the pages of the photo press of the ’60s and ’70s. There are pictures with titles like “the fat man,” “the Chinaman,” and “the black woman,” and scenes of people walking, shopping, talking, and living their lives. There are lots of wonderfully weird historical shots: Castro in 1947 as a clean-shaven student activist in a flashy tie; Fidel and Ché playing golf; Ché speaking with Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

Most of the time, the pictures are presented because of what they show, not as a form of visual art. To understand why the photo was taken, you either have to already know who the people in the picture are or you have to read the captions. Miguel Vinas’ 1993 photo of women praying at a shrine to the Lady of Miracles in Columbus Cemetery does not look especially miraculous on its own.

In the text that accompanies the book, Jenkins writes about the creation of art schools and the evolution of the plastic and visual arts in Cuba, but he doesn’t seem to think about photography as an art in itself. He includes photographic portraits of fine artists, and there are plenty of graphically interesting, beautifully composed pictures, but there aren’t really any photographs that were made as fine art.

On the other hand, Shifting Tides is concerned more with the art history of Cuban photography than with photographs of history. Wride divides the pictures according to the interests of what he sees as four broad evolutionary generations of Cuban photographers: The Cult of Personality, Everyday Heroes, Collective Memory, and Siting the Self. In the first generation, photographers celebrated the great leaders and heroes of the Revolution. Alberto Díaz Gutiérrez, who is known as Korda, is one of the icons of this first generation. Korda began his career as a high-society fashion and advertising photographer. In 1959 he joined the Revolution. Eventually, he became Fidel’s personal photographer and shot “Heroic Guerilla,” the portrait of Ché that became one of the most published images ever. (Even if you’ve never heard of Korda, you probably know the poster or the T-shirt version of his most famous work.)

The next group of photographers continued to work in the documentary tradition, but focused their lenses on the common people doing the work of the Revolution. Wride presents individual photographs and reproduces layouts from magazines like Cuba Internacional, which featured photo essays about things like school-building projects. Wride seems to have chosen pictures as much for their style as for their content, like José A. Figueroa’s luminous landscapes of newly cleared roads twisting through jungle hills, from the 1972 series “The Sierra Road.”

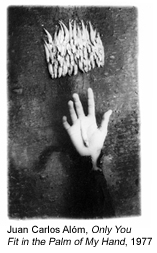

The next wave of photographers included the first graduates of the new art schools, and as Wride notes, their work is a startling break with the visual modes of their predecessors. While still focusing on the details of domestic life, they began to experiment with manipulated images. They created tableaux to photograph, altered the images that they captured with their cameras, and juxtaposed images with text. Rogelio López Marin’s 1986 series “It’s Only Water in the Teardrop of a Stranger” is a fantasia of swimming pools. In image after image, the water of the pool is replaced by ocean waves, rocks, the trees of a city park. The montages still show the realities of life in Cuba, but in the language of dreams and art galleries, not documents and news magazines.

The final group is the generation of the ’90s and the 21st century. These artists have pushed the details of history and domestic life further into conceptualization, abstraction and self-reflection. Pedro Abascal’s architectural details become gestures of light and shadow, and Abigail González stages poorly lit, gritty, roughly composed series on subjects like the intimate details of a woman’s life so that the pictures look like a documentary project. The series is as much about the process of making and viewing photography as it is about its figurative subjects.

I admit I am surprised that some of these photographs exist. Wride asks how art is possible in isolated, repressive, impoverished Cuba, but he doesn’t do much to answer his question about how these conceptual artists support themselves. Is the Cuban government really paying artists to make pictures like these? The day-to-day politics and economics of contemporary Cuba are so foreign to us that it’s hard to imagine how the most conceptual of these projects came to be.

While I wish there were a little more analysis, I also wish there were a little less design. The book includes details of some of the pictures, with odd, off-kilter crops that don’t reveal anything particularly interesting about the photos, and sometimes the images are shunted off to the side of the page for the sake of white space. The design doesn’t add anything to the work, and it can be confusing: Was the original text accompanying these images in English or Spanish? The pictures in the book and the largely unpublicized group of photographers who made them are exciting enough without these tricks.

Even with their vastly different approaches to the subjects, there are a few pictures that appear in both books. One of them, Korda’s photograph “The Quixote of the Lampost, Havana, 1959,” seems like a good emblem for this particular moment for Cuban photography, and for the idea of Cuba. In the picture, a man has climbed above the multitudes at a street rally to a precarious seat on the top of a street lamp, where he sits surveying the world below him. Wearing a giant sombrero with an upturned brim, he floats above it all, somehow risen above the push and pull of the throngs below. It is a lovely scene, with diffuse light on the sea of hats and flags, faces and banners below. Our hero seems to be in an admirable position, but inevitably, a number of questions arise. How did he get up there? What is his next step? He can spend some time savoring the view and the glories and triumphs of his ascent, but soon he will either have to find a way to climb back down to earth without breaking his neck, or he will have to figure out how to fly.

Jake Miller has written about photography for The New York Times, City Limits, and Science.